Modi & the Monk

It was the ‘double-engine’ magic of Modi-Yogi at work in UP. In the run-up to 2024, the unambiguous message is that leaders like Adityanath will give no quarter to slow-footed rivals

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

Rajeev Deshpande

Rajeev Deshpande

Ullekh NP

|

11 Mar, 2022

Ullekh NP

|

11 Mar, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/CS1.jpg)

(Photo: Ashish Sharma)

PRIME MINISTER NARENDRA MODI can take a bow as even his most persistent critics may not be able to grudge him credit for not only neutralising anti-incumbency but also making ‘pro-incumbency’ saleable at the hustings. Of the states that went to the polls this February and March, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) big win in Uttar Pradesh (UP) will hold attention, marking as it does a consolidation of the saffron base in India’s politically most significant state. But the repeat wins in Uttarakhand and Goa are no less remarkable as these are so-called ‘swing’ states where either incumbents get turfed out or coalitions are the order of the day. The return to power in Manipur also indicates that BJP’s last win was not a fluke and the margin of victory seals Congress’ decimation. Modi upstaged all others as the peerless campaigner rallied the masses and was a magnet for fence-sitters. Since occupying the national centrestage as BJP’s prime ministerial nominee in 2013, he has redefined election campaigning in India. This time round, too, well into his second term as prime minister, his spell in states his party has won is indisputably obvious.

In Manipur, Goa and Uttarakhand, he had a pivotal role in reversing anti-incumbency trends through energetic campaigns, promising that BJP would make good on its pledges and that the alternative was all about dynasty and “anti-development”. In UP, it was the “double-engine” magic of the Modi-Yogi Adityanath duo at work, much to the anguish of those who had poked fun at the expression. Though Modi had dented the domination of Mandal-era caste politics as early as 2014, he has over time become a unifier of a wider social base that has steadily veered towards BJP since he helmed the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government. His overarching vision of nationalist convergence was on display as the results of the five elections trickled in, underlining the political decline of Congress. That BJP was able to make unexpected gains even against anticipated anti-incumbency and sealed the fate of Congress in the Northeast is testament to Modi’s force of personality in turning the tide in his party’s favour even in the hardest of situations. It also meant that the ‘positive’ mantra of peace and development in the insurgency-hit Northeast has caught the imagination of the people.

While the caste calculus has seen an overhaul, as on earlier occasions, in these elections, too, the recurring Muslim-Yadav script saved the main contender and Samajwadi Party (SP) scion Akhilesh Yadav from further embarrassment as he vastly trailed expectations. But with the Yadav community becoming increasingly aware of the limitations of this inorganic tie-up, the association may now be under stress thanks to more robust—and rewarding—options for political alignment. These elections, especially in UP, saw a massive and consistent consolidation of non-Yadav Other Backward Classes (OBCs) who continued to repose faith in the much-underrated Modi-Yogi electoral powerhouse.

YOGI ADITYANATH IS an early riser who, according to people close to him, has advanced skills at growing plants. Every day when he is in Lucknow, once his matutinal exercises and prayers are over, one of his inviolable habits, it is said, is to spend time in the lovely garden at the chief ministerial residence where a gooseberry tree enjoys pride of place. Gooseberries from his official home were on display at an agricultural produce exhibition held not long ago at the UP Raj Bhavan. The “super active” chief minister, according to a close aide, still manages to start his work early, reaching his office before 9AM for the task he describes as “watering the state to growth”. People close to the powerful monk-politician prefers to believe that his gardening acumen—the intuitive knowledge of ‘buts’ and ‘what ifs’ of the craft that minimises mistakes and maximises returns—reflects in the way he cultivates vote banks, is dedicated to nurse the state from its poor reputation, and mulches his way into reaping the fruits of hard work.

Whether one finds logic in such a comparison or not, where Adityanath scores full marks is where his rivals and detractors have underrated and underestimated him: in endearing himself to women voters and the poor besides bringing order in a state notorious for its lawlessness, as voting patterns suggest. The result: returning to power in a state where no other incumbent chief minister has done so after a full term, a feat that carries him to the apex of electoral glory. Not only has his party won in pockets where it was expected to suffer setbacks for a flurry of reasons, including farmer protests, an alliance between influential caste groups, alleged disenchantment of backwards and the poor and so on, but it decimated the opposition even in its traditional strongholds against what was considered insurmountable odds. Its advance in western UP, an area affected by the farm agitation, and where SP and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) came together, is a case in point.

As with Adityanath, who started off with a negative perception of being an individualist and intemperate, he has now become simply the first among son-of-the-soil BJP leaders in the state to acquire a halo and use that charisma to lead his government and party on the fast track of political gain. Of course, one of his predecessors, the late Kalyan Singh, did have tremendous mass appeal in his prime, but then his influence was largely confined to certain groups, including hardliners among the Hindutva fold and sections of OBCs, Singh himself being one: from the Lodh Rajput community. Adityanath has become an icon of the youth and earned the support of women voters.

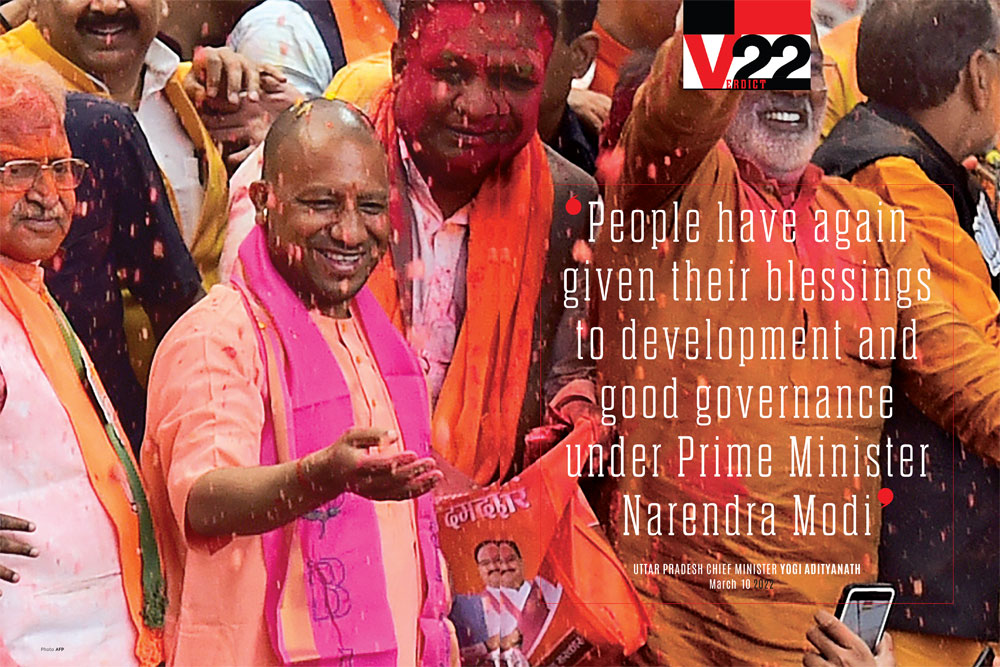

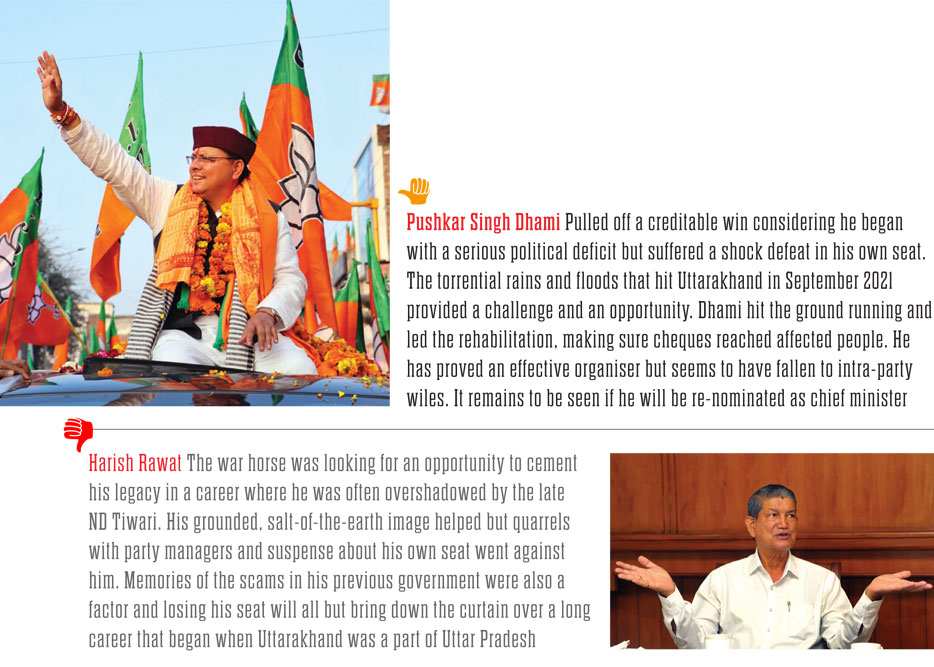

Yogi Adityanath As the election closed, the discussion in UP was on the likely margin of BJP’s win, rather than if it would retain office. At the centre was Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath whose energetic campaign has pitched him to the forefront of BJP’s ranks. A big win not only ensures him an unprecedented second term as chief minister but separates him from other NextGen saffron leaders. UP is seen as much as his victory as that of Prime Minister Narendra Modi

From that context, Adityanath, with the blessings of Modi (the photo of the prime minister with his hand on Adityanath’s shoulder was a defining moment), singularly breaks multiple barriers of UP politics and busts theories that arguably support a certain view aired by pundits who have not seen the new trend coming. “I have come to break myths,” he told Open in a recent interview (‘Security Is the Foundation of Vikas and Good Governance’, March 14). It is a trend that marks the fraying of old ways and announces realignment of caste equations in the most populous and complex state that sends the most number of lawmakers to Parliament. His opponents seem apoplectic about his rise and also about his style of governance that is strict and no-nonsense. But the 49-year-old, who has, thanks to this stunning victory, entered the league of BJP’s all-time luminaries, has proved to be light years ahead of his detractors and their politics stuck in the quicksand of 1990s Mandal-era caste dynamics. Caste affinities and identities are not going to disappear, but across caste groups there is a rethink on what works best for them: vote for governance and an umbrella organisation or vote for caste or withering regional entities? They seem to have chosen the former, denting, in the process, once entrenched, entitled and self-styled contractors of caste. The poll reverses of OBC leaders, including former BJP minister Swami Prasad Maurya who joined SP ahead of this year’s polls in a dramatic move, confirms new realities. The so-called OBC rebellion never happened.

While the emphatic win in this year’s election helps the BJP-led coalition recover from the drubbing it received in West Bengal last summer, Adityanath finds himself catapulted into a larger-than-life figure, next only to Modi whose sway over the state’s voters remains intact. Modi found in Adityanath just the right fit. The tout ensemble, as BJP insiders argue, is the emergence of the double-engine that decimated hyped mobilisations around farm discontent, inflation woes and lack of jobs in the time of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The denouement of the polls in UP, which saw a more or less bipolar contest between BJP and challenger SP, is symptomatic of much more than that: it further weakens the opposition nationwide in the run-up to the 2024 General Election with no credible alternative in sight for the Modi-led BJP juggernaut. Akhilesh Yadav, whose last win was in 2012 at the expense of his father and paterfamilias of the once dominant SP Inc, Mulayam Singh Yadav, has lost consecutively for the fourth time—in 2014, 2017, 2019 and 2022—failing to secure victory in his own right. The other contenders, however minor they may have appeared in this election, such as the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) of former chief minister and Dalit leader Mayawati and Congress’ Priyanka Gandhi, who apparently addressed 209 rallies and roadshows in the state, surpassing even Adityanath who spoke at 203 poll events, bit the dust. The downward spiral of SP, BSP as well as Congress, all of whom had dominated UP’s politics either in the pre- or post-Mandal years, proves once again that the rules of engagement in the north Indian heartland have changed for good. Congress and the rest have fallen victim to electoral tactics and traits from the pre-2014 period of Indian politics and failed to win over a wider social base. Priyanka Gandhi, Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav have all turned out to be wrong people in the wrong place at the wrong time with the ground beneath their feet slipping away. Especially when gauged against high expectations prior to the announcement of the results, the SP scion’s failure to pull in as many votes as anticipated bring to the fore the political limitations and lack of vision on his watch. BJP’s gains even in Lakhimpur Kheri, where some farmers were killed during a protest against the now-repealed farm laws and which in turn reportedly triggered passions against the party, are proof of the opposition’s failure to cash in on opportunities. As a result, UP, too, has come under the spell of the Gujarat model of politics where the nearest contender to BJP is many notches down and insignificant.

BY AND LARGE, BJP, with the ascent of Modi, has internalised the teachings of socialist thinker Ram Manohar Lohia, who was also a man of action and placed utmost importance on the removal of segregations of caste as well as gender. According to him, caste and gender biases were primarily responsible for the decline of the spirit in India. He wanted any effort to eradicate poverty to be complemented by elimination of discrimination of women. He had called for an all-out war on what we now call toxic masculinity besides larger representation for backward classes that was immortalised in the slogan, “Samyukt Socialist Party ne baandhi gaat, pichade paave sau mein saath (SSP, or Samyukta Socialist Party, has made a vow that backward should get a share of 60 out of 100).” Lohia’s 60 per cent included women, but under SP, which claims his legacy, it was largely meant for a single community, the Yadavs. In Adityanath’s victory, women became the vanguard of his success story. That is not surprising considering the time and energy he expended on implementation of women-centric programmes that covered all key aspects in the lives of women, from prenatal health and birth and free rations, affordable food, nutrition and overall health, financial aid for primary and higher education, self-employment, small loans and sustained livelihood support for the socio-economically weak, besides better law and order. All of this unleashed a silent revolution among women in favour of his government, resulting in an unprecedented 11 per cent hike in women voter participation (by the end of the second-last phase of voting) in the just-concluded Assembly election. To be precise, welfare schemes for women in the state went far beyond the much-talked about Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana that started in 2016, fully subsidising the security deposit and other charges for gas cylinders of different sizes to BPL families. The crucial schemes post-2017 included the Bhagya Laxmi Yojana which provided financial aid to girls from poor families in the form of bonds worth ₹ 50,000 right up to graduation, the Annapurna canteens in several district tier 2/3 towns forking out breakfast, lunch and dinner at a total daily spend of only ₹ 13 per person, the Kayakalp scheme to improve the condition and education quality in government schools to encourage girl children to continue their studies to arrest dropouts due to social issues related to health and hygiene. The School Chalo Abhiyan supports girl students with school uniforms, shoes and so on (has benefited over 60 lakh girl students and supports the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao). Besides, there was a raft of others, too, including the CM Kanya Sumangala Yojana which provided financial support of ₹ 15,000 for education, the CM Samuhik Vivah Yojana, that gave ₹ 51,000 to girls from poor families (over two lakh women stood to benefit), the Suposhan Yojana under which families are funded for nutritious food and families that can keep cows at home are provided with a cow and ₹ 900 to get free milk for the family. The Mahila Samartya Yojana also provides financial support to women’s help groups that help women in rural areas become self-reliant and the Central government’s Swamitra Yojana facilitates women of families to get their properties registered in their names.

Merely listing these is an arduous task, and much more Herculean was their successful execution that made Adityanath a darling in the state’s households. Similarly, the thrust of the poor too clicked, as explained later.

Targeting women for welfare measures by itself was synonymous with outreach to the poor. During his stint as chief minister, Adityanath roped in banks to train over 70,000 women to work as banking correspondent sakhis to ensure last-mile connectivity. Building of 2.61 crore new toilets was meant to offer safety and dignity for women. Nearly 70 lakh free gas connections were provided to eligible women and women from over 40 lakh families were beneficiaries of the PM Awas Yojana.

That’s not all. As Adityanath said recently to Open in an interview, “The foundation of vikas and good governance is security…A state like UP is today talking of security and good governance. This is a good sign and people are appreciating it.” In fact, he was being euphemistic at best. Adityanath’s coup de grace to parties that had been in power and did nothing to improve the piteous law and order situation in the state was to launch a ruthless crusade against dons and gangsters who had enjoyed political patronage in the past but now find themselves in jail. That earned him goodwill across a wider social base that his rivals didn’t immediately take note of. Women voters, cutting across the rural-urban, caste, community and class divides, were impressed. Soon, the Mahila Shakti Mission set up women’s help desks with adequate police backing in 350 districts in the first phase. More than 218 fasttrack courts were set up to deal with crimes against women, including domestic violence. More importantly, helplines swung into action and 20 per cent of the police personnel in the state police are now women. More efforts are afoot to raise their representation in the forces. Adityanath also unveiled schemes to light up the streets of towns and cities across the state to bring down crimes against women in a state once infamous for power outages and gender crime.

IT IS NOT THAT BJP went to the polls expecting a cake walk, as Union Home Minister Amit Shah himself reminded the cadre time and again that each election throws up unexpected challenges and polls, after all, have to be won. But unlike in 2017, the party and its allies had much more to brandish in terms of governance and leadership. Back then, the flagship scheme was Ujjwala and the party had no chief ministerial face ahead of the Assembly polls. It wasn’t a bipolar contest back then with SP and Congress in alliance and BSP on its own, opening up a triangular competition. But BJP came out triumphant, winning 312 seats on its own, up 265 seats from five years earlier. SP lost 177 seats to win only 47. BSP won 19, down 61 from 2012 and Congress a mere 7 from 28 earlier. BJP repeated its grand show in the 2019 re-election of Modi as prime minister against a grand alliance of BSP and SP that seemed to have caste arithmetic favouring them. But results proved otherwise: the BJP alliance won 64 of 89 Lok Sabha seats and the BSP-SP alliance 15 and Congress a single seat—that of Sonia Gandhi from Rae Bareli; her son Rahul Gandhi was among the prominent losers.

Notably, Adityanath’s endurance has to be weighed against the scales of myriad challenges he faced, including the pandemic, which caused panic-stricken migrant workers to return to their villages in his state, and the concomitant loss of jobs in the face of unprecedented uncertainty amidst the scourge. Open has written extensively about how the Adityanath-led UP government’s Covid strategy was remarkable not only in terms of spending on public health but also in empowering nodal officers who could think and act on their feet. It was a radical break from the state’s earlier reputation as a laggard and it led in terms of scale of vaccination and improved ease of doing business ranking, and in building infrastructure and in bringing under its welfare net large sections of groups ignored by previous dispensations. Last year, the government won praise from the Supreme Court for rising to the occasion when people who had migrated from the state to cities returned during the Covid-induced lockdown. The court said on June 28, 2021: “The state of UP is maintaining a robust system of registration of such migrant workers as they come into the state. A portal…has been created on which all relevant details of all migrant workers are to be uploaded in real-time. As per the data available with the director, training and employment, Uttar Pradesh, as many as 37,84,255 migrant workers have returned to their native places during the entire Covid-19 pandemic period.”

The surge in UP’s infrastructure development is a story on its own. It was stellar even in health and education. Adityanath said recently to Open, “Look at UP’s health infrastructure, between 1947 and 2017, only 12 medical colleges came up. We are in the process of setting up a medical college in each of the 75 districts. We have seen 39 colleges come up in the government sector.” The state has a capacity of four lakh Covid tests a day and ICUs in every district.

Again, in the five states—UP, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Manipur and Goa—where Assembly polls were held, the electorate has clearly moved on beyond certain election myths. That is especially true of UP, which has historically been projected as an underachiever. Open had examined at length this subject earlier (‘Five Myths About How India Votes’, February 7, 2022). These elections vindicate our observations about misconceptions and misinformation about the state that include its being a place that lacks basic amenities such as power, roads and water; and that there exists a formidable Jat-Muslim alliance against BJP; that the farmers mobilised for the massive strike against the farm laws were inimical to the Centre and state; and that OBCs are a monolith who stand with SP which, ironically, incurred the wrath of non-Yadav OBCs over decades for never giving them their due in exchange for votes. Another myth laid to rest was the projection of a composite Dalit vote bank that would not vote for any entity other than BSP. With BJP, as stated earlier, offering an umbrella for all socio-economic groups and covering them in its ambitious schemes, such myths stand exposed and are awaiting a burial.

Along with such formulations, another claim has been disposed of: that Muslims can hold a veto in elections. The re-assertion of Hindutva forces, coupled with welfare for all, irrespective of caste and religion, has done away with any preferential treatment for any section and replaced it with an all-encompassing package of social justice.

THIS ELECTION WAS definitive in more ways than one. For instance, the Muslim-Yadav combination was peddled as a ‘natural alliance’ forged on the common belief in a composite culture. Political pundits touted it as one of the finest examples of robust grassroots secularism.

Contrary to the depiction of this social coalition as rooted in very natural traditions of Hindu-Muslim amity, this was actually a relatively a new phenomenon. Both communities were part of the big Congress tent at a time when virtually every slice of the social rainbow was represented in the Grand Old Party and remained so for several decades prior to the tectonic shift of Yadavs that began in the 1960s. In the mid-1960s, Yadavs as a community started leaving the very crowded and politically claustrophobic Congress fold dominated by the upper castes and started drifting towards socialist platforms, driven by Lohia’s political ideology. This shift was prompted by the realisation that miniscule upper castes in Congress were using numerically preponderant sections to institutionalise their hold on electoral politics.

In the watershed year of 1967, the intermediate castes were able to display their political clout in a manifest way and signal a crucial shift in electoral and social dynamics. And translate this into electoral seats. This saw the establishment of the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal (SVD) governments in UP and Bihar. Mulayam Singh Yadav, then of Samyukta Socialist Party, became a first-time MLA in that year, as did Kalyan Singh, of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. In UP, this was the first non-Congress government, led by Chaudhary Charan Singh. The development remained limited to UP and Bihar. Though there were no Jats in eastern UP, he got the backing of farming communities and intermediate castes like the Yadavs and the Kurmis, a support that sustained up to the mid-1980s.

While Yadavs chose to remain outside the Congress umbrella since the late 1960s, the Muslim vote stayed firmly with the party in the 1971 elections which the party won. But in 1977, when Congress got drubbed in the General Election, every community deserted the party. 1980 was a classic case that demonstrated the hollow claim of traditional amity and electoral unity between the Muslim and backward-class voters: the latter remained outside Congress but Muslims backed the party, as also in 1984. The Muslim community vote left Congress in the 1989 elections, but only partly, to back the platform floated by VP Singh. But it was not wholesale support, since BJP was part of that alliance. Muslim voters left Congress for two reasons: one, the pull exerted by VP Singh and two, a less talked about event that showed Congress in poor light: the Bhagalpur riots. The riots of 1989 in Bihar’s Bhagalpur involved Hindu-Muslim violence that started on October 24 that year and carried on for a whole of two months, engulfing the city and some 250 surrounding villages. Over 1,000 people were killed and another 50,000 reportedly displaced as a consequence of the violence. It was considered the worst instance of Hindu-Muslim violence in independent India at the time and continued to resonate years later. (In 2015, Nitish Kumar, despite an alliance with Congress, played the card prior to the elections by setting up a probe that denounced the riots as a “national shame” and “barbaric”, a telling indictment of the SN Sinha Congress government of the time.)

Attempts to woo Muslims as a community for their votes gained momentum significantly after the 1989 elections, in which VP Singh got the support of Mulayam Singh Yadav in UP, Lalu Prasad in Bihar and Sharad Yadav in Madhya Pradesh despite the presence of BJP in the anti-Congress coalition. Jats went with him, too. The Mandal Commission report implementation during his stint firmly cemented OBC support behind him. Until then, socialists had little reservation about aligning with BJP, but post-1989, Mulayam Singh refused to go with BJP. Mulayam Singh was the first Yadav leader to defy the prevailing socialist line. In fact, a serious difference of opinion had emerged between him and Karpoori Thakur at the time and these differences began to come out in the open. Socialists until then, including Lohia himself, had freely partnered with the Jana Sangh and later, BJP. For them, anti-Congressism was the dominant ideology.

Lohiaites believed, and rightly so, that Congress, bolstered by its first mover advantage and a historic legacy, remained formidable as long as the opposition remained divided.

The disintegration of Congress began in the late 1980s when the upper castes, too, began deserting the party. Muslims, who saw BJP as the problematic issue, started scouting around for the most viable political option for defeating BJP. That would lead them to versatility in exercising their options—in some geographies, they aligned with the Janata Dal; in some others, they dumped it for better political options. In UP and Bihar, Muslims concluded that since upper castes had more or less left Congress, it had ceased to be the key option for them to keep BJP at bay.

The new political option came in the form of Mulayam Singh in 1989. His victory could not have been described as a Muslim-Yadav victory because he was the chief minister of Janata Party that enjoyed support across communities. (The state Assembly elections were held along with the Lok Sabha polls.) However, Mulayam Singh had started robustly playing the ‘secularism’ trope to build and cement his credentials as the key voice against BJP in UP. Muslims and Yadavs, thanks to their sheer numbers, made for a very powerful electoral combination. In UP and Bihar, their combined share in the voting population was close to 27 per cent. So, any leader who gained their support started with a solid backing of 27 per cent of voters.

The graph of Muslim and Yadav electoral support to parties and leaders shows a clear ebb and flow, both separately and together, based on sheer, unsentimental power calculations that had little to do with ideology or the claims of communal amity.

There was competition among the Yadav community’s biggest leaders to be seen on the right side of Muslims. Several conspiracy theories made the rounds on why BJP stalwart LK Advani was arrested during the Ram Rath Yatra in Bihar. He was headed for UP. Anyone would like his state to be free of trouble. VP Singh also had the option of arresting Advani, who was entering Bihar by the Rajdhani Express, before the train had reached the state. However, some claim that VP Singh was apprehensive that if Advani were arrested in UP, Mulayam Singh would get the political advantage and become a taller hero than himself. Mulayam Singh had already earned immense credits for tough ‘secularism’ by ordering the state police to fire on the kar sevaks and his unwholesome statements on Ram. The arrest of Advani would have been another feather in his political cap, boosted his cult image and would have made him unstoppable.

In the 1991 Lok Sabha polls, after all that he did to curry favour with the community—firing on kar sevaks, etc—Muslims deserted Mulayam Singh. In that election, Mulayam Singh got only four seats. The Janata Dal did much better although VP Singh was almost a spent force after the collapse of his national government in November 1990. Mulayam Singh went with Chandra Shekhar’s Janata Dal (Socialist) and remained in the chief minister’s seat in Lucknow with the support of Congress. But his government fell when Congress withdrew support in April 1991 after it first withdrew support to the Chandra Shekhar government in New Delhi. Chaudhary Ajit Singh’s writ did not run beyond a few pockets around Baghpat in western UP, despite his father’s legacy. Muslims did not consider Mulayam Singh’s party as a credible vehicle to defeat BJP and refused to get swayed by old-fashioned considerations of gratitude and indebtedness. They were realistic and went by the sole calculation of backing the party best suited to defeat BJP. In the midterm elections to the UP Assembly in mid-1991, Mulayam Singh’s party lost power to BJP.

The Yadav leadership, too, was a divided lot. After the collapse of the HD Deve Gowda government in 1997, Sharad Yadav and Lalu Prasad joined hands to scuttle the chances of Mulayam Singh for the prime minister’s post. Despite all the myth-making that these social alliances were forged in ideology, common belief in secularism, etc, they were based on hard-nosed, clear-eyed political calculations.

Part of the reason why the Muslim community in both UP and Bihar chose to go with the Yadavs could have been the calculation that leaders from the community would be more acceptable to the entire spectrum of OBC communities. That, however, generated a backlash the moment Yadavs got a bigger slice of political power. The caste groupings among OBCs resented the exercise of power by Yadavs as the new elite.

It was only to be expected that in many locales, Kurmis, Koeris or Lodhs were just as better, or worse, off as the Yadavs. Moreover, since they fought together, they could not be expected to be reverential to the Yadav leadership. They saw the Yadavs as equals and refused to be in awe of their political clout or resigned to it.

The Yadav leaders were challenged mainly by other OBC leaders. In Bihar, Lalu Prasad’s inability to take along other castes in the OBC spectrum benefitted Nitish Kumar and BJP. In UP, BJP and BSP have been most successful in winning the support of large sections of non-Yadav OBCs, as demonstrated by Kalyan Singh two decades ago.

The result is certain to boost the confidence of BJP that with sustained work, it can attract significant sections of backwards into its fold. If it meets with significant success, it would be the undoing of the great ‘secular’ experiment and the collapse of the hyped MY trope. Then Yadavs would lose their value and effectiveness as secular allies of Muslims, making them vulnerable to poaching by others.

ON THE FAR WALL in his office is an imposing, giant screen. This is the room in which he meets bureaucrats at his 5 Kalidas Marg residence each morning to unfailingly and diligently run through the implementation status of various schemes and programmes initiated over the five years of his tenure. The numbers on the wall are live feed and a 24X7 check on the dozens of Central and state yojanas for the residents of UP. Glitches are discussed, good work acknowledged, weaknesses in delivery mechanisms ironed out, additions, expansion and tweaking of existing schemes all planned in minute detail.

Adityanath’s work ethic is a seamless extension of his life ethics: no frills and fancies and a focused dedication to the work at hand: governance. On the day Open met him was the last day of the poll campaign for the third phase of polling. There was a hectic last-minute dash by all key players to meet deadlines and wrap up key rallies, roadshows and addresses. Adityanath, star campaigner for his own party and government, was scheduled to address four poll rallies by the end of day and was to leave urgently for various places at 11AM. At 9AM, two hours prior to departure, there would have been last-minute exigencies to be attended to prior to his leaving, hustle and bustle by the security personnel, urgent issues for bureaucrats to deal with and hectic pushing and shoving by political leaders and their cloying hangers-on, with their dozens of flashy SUVs cramming the driveway, all claiming the chief minister’s immediate attention. But at the chief minister’s residence, there was none of this clutter, confusion and needless theatrics. No political workers thronging or cringe-worthy platoons of hangers-on. Only his staff and a handful of officials dotted the landscape. Adityanath had calmly gone through with his daily interaction with the bureaucrats in the early hours of the morning prior to leaving for his campaign tour. His simple, stark and effective style of functioning marked a departure from the ‘band, baaja, baaraat’ show that had been a permanent fixture at the residence of the chief minister of UP for decades. It was even a source of acute discomfiture to many in the administration and his own political ecosystem. That morning, going through the implementation of schemes and programmes custom-tailored for the women of his state, Adityanath dwelt on his hands-on interest in their successful implementation by narrating an incident of his visit to a Mushahar habitation on one occasion. One of the women there, clearly hard working but in tattered clothes and tired demeanour, was among those he met. Asked if she was benefitting from his government’s schemes, the woman told him that she and her family had no “colony”, a synonym for state-sponsored housing for eligible citizens from economically weaker sections and communities such as hers. Adityanath immediately summoned the official concerned and directed that her details be taken and she be allotted state housing. Six months later, on a repeat tour of the same habitation, the woman welcomed the “Baba” to her two-room abode. Was she now making a living then, he had asked her. She replied that her husband now earned from push-cart (redhi) sale of vegetables and she had been saving money with which she planned to buy a bullock and link herself to the government’s scheme for sale of cow dung. “The poor are needy, not greedy. They just need that firm hand up to make a start and they are hard working enough to chart a course for a dignified living by themselves. They are not looking, unlike others, for freebies and handouts and largesse,” he replied to a question on whether he planned to ensure that she and her family got employment for a sustained livelihood. When the poor say “aapka namak khaya hai”, Adityanath maintained it should not be read as a sign of abject servility but of thanks for a hand-up, a legitimate and rightful opportunity to start fixing their own issues. Far from being a phrase that takes away agency, it should be seen as one that reinforces their agency, Adityanath noted.

Adityanath’s way of conducting business is a departure from the flashy ways of previous governments. His work ethic and style of functioning, quietly focusing on carpet-bombing essential welfare services and schemes on all sections of society, alongside special group-targeting, gave momentum to a critical mass of support to his government, fuelled by public trust in his ability for good governance. Together, that style highlighted the sharp contrast with the governments run by SP in the pre-2017 period and the tendency of SP leaders, not excluding Akhilesh Yadav, to turn their governments into some sort of Yadav Inc, a private limited company with the community’s rigid monopoly on wielding power and influence across the spectrum, from industry to agriculture to infrastructure to all things economic and political in the massive state. Unsurprisingly, Adityanath’s method triggered heartburn, complaints and anger. There were also many efforts to paint him as a chief minister who was brazenly biased towards his caste brethren. Stories were circulated about upper-caste Brahmin members of his administration being sidelined, neglected, unjustly ignored and they, in turn, fuelled a contrived narrative of a social rupture among the upper castes with the Brahmins. There was also another price to pay for his work style that unflinchingly demanded accountability at all levels of the administration.

Modi’s faith in his handpicked man to head UP never wavered, right through his adept handling of the Covid wave, the protests against CAA-NRC. (Adityanath was the first to pass an executive order that would allow the state government to confiscate the property of those charged with destroying public assets during the protests.) Although it is now being challenged through the courts, the move nonetheless received much public praise. His focused and aggressive implementation of Central and state welfare delivered both essential rations to all needy and money transfers. “What’s truly impressive is that he doesn’t rely on speeches and briefs written by bureaucrats during Covid-19 combat strategy meetings with the prime minister. He would use the precise time allotted to him to succinctly explain his government’s performance on the agenda items listed for the meeting,” an official in the know said.

MODI AND YOGI complement each other perfectly in many ways, making for a powerful political duo that is virtually unbeatable at the hustings and a combination of forces, at the Centre and the state, and one that could power a favourable electoral tsunami for the “double-engine sarkar”. The unwavering backing from Modi to Adityanath did not come only on account of the latter’s stellar governance skills, his determination and his work ethics; they share a whole worldview.

Of the two, one belongs to the OBC community and the other to an upper caste. But there were many things in common in their lives. Both hailed from economically weak families. Modi, the only one in his family of six siblings to not change his surname, hailed from the backward Modh-Ghanchi caste. Modi’s mother Heeraben’s own journey of struggle to raise her six children after the demise of her husband is often narrated to illustrate the modest means of his background and the hardships he had to endure. Growing up in a relatively poor household and having none of the privileges of children of his age from better-off families also meant that Modi was determined to make a mark in life. In turning around the fortunes of the party in Gujarat—a feat considered impossible at the time decades ago—to his emerging as the super chief minister before he took over the reins himself for the next 15 years in Gandhinagar, Modi made it his mission in life to turn adversities into opportunities. And then, in 2014, he was elevated to the prime minister’s office of the largest democracy in the world by a stupendous electoral victory.

Like Modi, Adityanath, too, came from a large family of many siblings and graduated in mathematics. Hailing from the Nath community of the Thakur/Kshatriya caste, his father was a forest department official and his mother, Savitri Devi, a homemaker. His sister sold tea at a shanty. With no political background to his family, Adityanath’s schooling in politics came in 1996 when he managed the poll campaign for his mentor in Gorakhpur and became MP for the first time from the seat two years later at only 26 and then repeated that success five times. He was last elected MP in 2014, a post he gave up after he was handpicked by Modi to be the chief minister of UP in 2017 following BJP’s landslide win. Adityanath became the first full-fledged religious leader from a Hindu mutt to take the office, an unprecedented development, with the exception of Uma Bharti’s short-lived elevation to power in Bhopal.

Modi’s arrival on the national scene and open embrace of all things Hindu in public had dramatically impacted the incentive to vilify Hinduism. Also, the general mindset prevailing for long in society—that the Hindu could not do the very things connected to the practice of his religion that other communities could, without feeling diffident or guilty—was radically restructured. As prime minister, Modi went on to break entrenched moulds by visiting sacred Hindu temples including in his parliamentary seat, Varanasi, in Mathura and Ayodhya, in Kedarnath and Somnath, and elsewhere. He wore vermillion forehead markers, sported saffron vestments, chanted shlokas in Sanskrit, quoted from scripture in public, and from the Bhagavad Gita. Modi was also liberal in his patronage of important places associated with the Hindu religion and its braves from history. These were images seared indelibly in the collective consciousness of the Hindu masses, stemming from the brutality of a thousand civilisational cuts inflicted by Mughal rulers like Babar and Aurangzeb and others who razed these sites of Hindu faith to build mosques. The open advocacy by Modi of their reconstruction and celebration triggered a massive boost to Hindu ethos and end to minority appeasement in politics and society. One that had normalised the mollycoddling of minority orders and institutions alike for decades by the Hindu elite, led by Jawaharlal Nehru, who appeared to want to overcompensate for India’s global image of an impoverished subcontinent of rope tricks, elephants and snake charmers by persistently brushing the long traditions and cultural moorings of Hinduism under the heavy carpet of so called ‘modernity’. That the Hindu elite had a big part to play in the denial of Hinduism lent it much more credibility than it otherwise would have.

Modi’s bold espousal of Hinduism in public re-energised the proud assertion of the religion and conviction in it by a new generation of youth that rejected the guilt and the shame. That unapologetic owning of Hinduism in public is a playbook that Adityanath, a leader sporting saffron vestments full-time as head of the Gorakhpur mutt, has borrowed from aggressively. As a party leader put it, “For UP, they are like Partha and Sarathi; Modi is the driver of the chariot, the pathfinder, the visionary and Yogi is the warrior following his lead, delivering blows against corruption and communal mindsets and the blows for unprecedented and universal development. It’s a winning combination.”

The pronouncedly spiritual bent of mind that both of them share has often been credited in the case of Modi and Adityanath for a marked detachment from the trappings of power and personal acquisitions, accentuating a personal image of incorruptibility. This, especially since neither is hamstrung by the compromises and deals typical politicians make. Another unshakeable faith for both Modi and Yogi is Bharat’s destiny as a Vishwa Guru. If Modi was a politician impatient for India and her cultural and spiritual legacy of centuries to take their legitimate place in the world order, Adityanath refused to be content, despite being a five-time MP, to be just one in a crowd among the BJP leadership. Both of them had an unquenchable thirst to achieve the impossible and put India and UP at the top of the ladder of success. Modi was intent on drastically changing the longstanding perception of UP as a BIMARU state and Adityanath, the vehicle he trusted to give this a massive push.

All of these qualities invested them with a moral surplus in leadership over and above anything remotely similar in other politicians, making them both pragmatic but refusing to yield to the pressures of trade-offs in achieving key goals. These were qualities that UP’s ordinary voters grew to trust implicitly and have strong faith in to transform UP radically, something that only a giant leap of faith, or two powerful giant leaps of faith, in this case, could do.

It is imperative that we talk here about the Dunning–Kruger effect, which is based on the idea that poor performers have not yet acquired the ability to distinguish between good and bad performances. Which means, they tend to overrate themselves because they do not see the qualitative difference between their performances and the performances of others. This has also been termed the “dual-burden account” since the lack of skill is paired with the ignorance of this lack.

No doubt, the Dunning–Kruger effect is relevant for various practical matters. It can lead people to make bad decisions, such as choosing a career for which they are unfit or engaging in behaviour dangerous for themselves and others due to their being unaware of lacking the necessary skills. It may also inhibit the affected from addressing their shortcomings to improve themselves. In some cases, the associated overconfidence may have positive side effects, like increasing motivation and energy.

THE PERFORMANCE AND PLIGHT of BJP’s opponents can be analysed through this seminal theory. The election results are bad news for Akhilesh Yadav, who hoped to challenge BJP; BSP supremo Mayawati, who sought to regain a lost relevance; and for the Gandhis, looking to refurbish Congress’ image as a national party with strong regional roots. Of the three hopefuls, it is Congress that has the most to despair as it was in contention in four states where it has been one of the principal poles for long and could have fancied its chances. UP was a long shot, though even a modest improvement could have been cause for some cheer. But this proved elusive. The Gandhi family bastions of Amethi-Rae Bareli are all but wiped out. The hara-kiri in Punjab, factional feuds in Uttarakhand, an obsolete leader in Manipur and desertions in Goa put paid to the party’s poll effort. Though each state presents a unique set of problems, the sum of the parts points to a deeper malaise that will be hard to address in time for the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, putting a question mark against Congress’ claim to be the core of any national challenge to BJP and Modi.

The electoral meltdown in Punjab has left all key players with egg on their face. Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi might, despite being the losing incumbent, have had something to talk about as he gained a profile he never had but then lost both his seats. The electorate too remained unimpressed by his elevation as the state’s first ‘Dalit’ chief minister, and no substitute for the party’s poor record in office. The would-be chief minister Navjot Singh Sidhu is even more distant from his dream than he was when, backed by the Gandhis, he launched a direct challenge to Amarinder Singh. Rather, he may rue that discussions with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), or even schemes to float an independent front, did not fructify. The entire episode, however, puts the spotlight on a bizarre progression of events in the past year. It started with a systematic assault on the authority of then Chief Minister Amarinder Singh, long close to the party’s first family. The reasons for a falling out were never clear. It could be that party bosses sensed a hitherto unreported incumbency. It is true that Singh wasn’t the most energetic of administrators. But then, apart from Kerala, Punjab was the only state that returned a bunch of Congress MPs in 2019. Yet, Sidhu presented himself as a ‘change agent’ the party needed, winning the backing of Priyanka and Rahul Gandhi. His maverick ways may have made less of an impression on Sonia Gandhi, but decision-making is now primarily in the hands of her children, more so with Rahul. The track Sidhu chose to challenge Amarinder was to rake up the ‘sacrilege’ case involving alleged acts of desecration that happened when SAD-BJP were in office in 2015 but which were also investigated after Amarinder became chief minister. The quashing of the SIT report on the incidents by the Punjab and Haryana High Court provided Siddhu with ammunition to take on his rival. It was a risky manoeuvre, laden with emotive overtones that could inflame public opinion, but had the backing of the leadership. Not one to shy away from a fight, Amarinder hit back, labelling Sidhu a national security risk for his proximity to Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan and army chief General Qamar Bajwa.

Till this time, Singh was faithfully towing the leadership line, encouraging the agitation against the three rescinded farm laws—powered mainly by Punjab-based farm unions—egging on farmers to lay siege to Delhi in order to pressure the Modi government. The farm laws had also ruptured the Akali-BJP alliance, depleting the challenge to Congress. And while the Centre was under adverse notice, the Akalis failed to make any gains despite their leverage with ‘panthic’ organisations lending muscle to the farm stir. But soon enough, the picture changed. Supported by AICC, Sidhu escalated his row with Amarinder and Congress infighting became the main locus of politics as governance predictably took a backseat. When Amarinder was finally yanked off the chief minister’s chair, things became even messier, as the serving chief minister was in the dark about a meeting of the legislative summoned to oust him. If all this smacked of vendetta against the party veteran, the decision to overlook Sidhu for the chief minister’s post only made matters worse. If the reason was Amarinder would not countenance a direct rival being elevated, no purpose was served as the veteran soon left the party and later allied with BJP. Moreover, Channi was an uninspiring choice while his Dalit credentials were untested as a poll factor. Party insiders feel Amarinder’s assertive ways and his streak of individuality just did not go down well with the high command. In contrast to the ugly scenes in Chandigarh, BJP’s decision to replace a tall leader like BS Yediyurappa in Karnataka and the entire cabinet, including Chief Minister Vijay Rupani, in Gujarat, was carried out with skill and little fuss. Though being in office at the Centre gave Modi and Amit Shah the heft to carry out difficult changes, the process nonetheless stood in contrast to l’affair Amarinder. To cap it all, Channi’s elevation failed to end the bloodletting, with Sidhu making it clear that he had only paused his ambitions.

The sub-optimal results are only likely to further delay the organisational polls, including the election of a full-time party president and constitution of a working committee, demanded by the G 23 dissenters. Earlier, the Covid situation was offered as a reason, but even now the ruling faction will carefully weigh the fallout of organising a party jamboree like an AICC session at a time of political flux. Will Congress introspect and change its tactics? The ranks of dissenters are likely to swell and become more vocal but prospects of a course-correction are dim. Despite repeated advice that personalised attacks on Modi do not work and can be counter-productive, Rahul Gandhi has not altered his views, convinced he needs to confront the BJP mascot head-on. His recent formulations on ‘Hinduism’, ‘Hindutva’ and ‘Hindutvawadi’ have puzzled senior Congress leaders, one of whom pointed out that venturing into such territory requires a thorough reading of the subjects, including the Supreme Court’s ruling on Hindutva and related issues. The sweeping attack on the government on all fronts, ranging from the policy on China to evacuation of students from Ukraine to alleged economic distress, finds a ready echo with ideological opponents of Modi-BJP, but this might be a case of preaching to the converted, fear Congress leaders worried at the party’s downward trajectory. Living in a political bubble reinforced by tuning into an echo chamber that supports its bias, prevents the leadership from undertaking an accurate analysis of its diminishing electoral clout. The belief that ‘institutional capture’ by BJP-RSS and ‘polarisation’ has unfairly skewed the electoral field in favour of the ruling dispensation—an important aspect of Rahul Gandhi’s letter resigning as party president after the 2019 Lok Sabha results—is in sync with the ‘democracy deficit’ narrative espoused by BJP’s critics and opponents but fails to inspire a wider following.

The more immediate question is about Congress’ prospects in the next General Election about two years away. Some of the key contests along the way—Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat later this year—and Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka and Rajasthan in 2023—are essentially BJP versus Congress contests. The current state of the party raises questions whether it can take on the BJP election machine by identifying weak spots in the saffron armour and sufficiently exploit them in the 2024 Lok Sabha polls. The official camp in the party feels that the national election is a different ball game and Congress remains the only real alternative with the experience and leaders capable of running a Central government. But there is recognition that regional parties will give no quarter in the leadership stakes as was seen in the Goa election where NCP-Shiv Sena and Trinamool (with local party MGP) contested separately. The Punjab blunder has hardly bolstered confidence levels in Congress as the spectacle of Amarinder Singh’s undignified ouster and Sidhu’s antics only deepened public disenchantment with the party and government. In retrospect, AAP’s Punjab win may be put down as a gift from Congress, as popular distrust with traditional choices opened the doors to an intrepid interloper. Looking ahead, given the family-centric nature of Congress’ functioning, it is unlikely that a leadership challenge will succeed. Regional satraps like the chief ministers of Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, Ashok Gehlot and Bhupesh Baghel, may get more leeway while the leadership’s capacity to intermediate and negotiate factional claims declines. After the 2019 defeat, Rahul Gandhi accused party seniors of being lukewarm about attacking BJP over alleged graft in the Rafale deal rather than considering that the campaign may have been off the mark. As things stand, Congress seems intent on doing more of the same as evidenced by Rahul Gandhi getting Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh to revert to the old pension schemes in what is seen as a rejection of BJP policies even though the new scheme prevailed throughout the United Progressive Alliance’s (UPA) 2004-14 tenure.

In the aftermath of the UP result, both SP and BSP find themselves back at the drawing board, but Mayawati may find herself in a tighter spot. The Dalit outfit was squeezed between BJP and SP, with the perception that the latter has better prospects persuading Muslim voters to ditch BSP. In the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, the SP and BSP alliance could not stop BJP but Mayawati’s party won 10 seats against SP’s five. There is no such consolation this time round. BSP’s majority in the 2007 state polls was powered by upper castes moving away from BJP as the party did not appear a contender and forwards saw Mayawati as preferable to Mulayam Singh. BSP has since not been able to replicate the magic, even though Mayawati campaigned actively before rival SP began its outreach. The salience of Modi and Yogi Adityanath ensured that not only BJP’s traditional base remained loyal but there was an accretion at the expense of BSP’s Dalit votes too. This creates an existential threat for the party that has crucially depended on leveraging the Dalit base with the caste-community of a particular candidate it puts up. Adityanath’s “Hindutva Plus” model that incorporates a heavy dose of welfarism poses a stiff challenge even as the perception that BSP is better at law and order than SP is eroded by the chief minister’s pro-active approach to fighting crime.

The shift in the Muslim vote, along with some addition by way of RLD and Rajbhar alliances, as also the race turning largely bipolar, saw SP’s vote jump to 32 per cent but it also hit a ceiling. SP’s seats have more than doubled, but it failed to cross a critical threshold, and a 10-11 per cent vote gap with BJP presents impossible odds. The silver lining is that SP will be seen as the alternative to BJP with Akhilesh Yadav a likely leader of opposition, a better outcome than BSP that has been swept aside. But like BSP, SP also faces the fading appeal of its caste-driven mobilisation and patronage architecture when in office. With BJP’s umbrella coalition of upper castes, non-Yadav OBCs and sections of Dalits proving durable over four elections, there might be some re-think in the SP base as well. The Muslim vote may not yet reconsider its antipathy towards BJP, but the utility of minority politics, as practised by ‘secular’ parties, is certainly under the scanner. SP has long supported local strongmen and facilitators who became the intermediary between the party and Muslim voters. But whether the immunity from law enforcement enjoyed by such leaders when SP is in office actually helps the wider minority community or only encourages a dependence on mafias, could become a point of discussion. Not only do these tactics trigger a counter-polarisation, and actually increase communal tension, the supplicant-master relationship is essentially unequal and exploitative.

This round of elections, seen as a semi-final to 2024, especially in UP, has resulted in an unambiguous message that leaders like Yogi Adityanath, pursuing their goals at a frenetic pace and with no sense of foreboding, will give no quarter to slow-footed rivals. Jubilant BJP leaders, therefore, cannot be faulted for saying that the people of four of the five states that went to the polls have hung many of their contenders out to dry.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha

Mumbai’s Glazed Memories Shaikh Ayaz