The Royal Reckoning

By her stature, Queen Elizabeth II had kept at bay questions that must be answered now. But is Britain ready?

Roderick Matthews

Roderick Matthews

Roderick Matthews

|

16 Sep, 2022

Roderick Matthews

|

16 Sep, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Queen1.jpg)

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip ride in the royal carriage in London, July 23, 1986 (Photo: Getty Images)

HERE IN BLIGHTY the blows just keep coming. In the last two years we have had Brexit, Covid, a massive energy crisis and, finally, the departure of a national figure of such unparalleled stature that we have no way to assess the scale of her loss. When we talk of big shoes, those of the late Queen Elizabeth are surely impossible to fill.

The smallest of global titans, she was grandmother to the nation, familiar from seventy years of coins, banknotes and stamps. Her cheerful confidence allowed her habitual pastel-coloured outfits to stand out in any crowd. And there was always a crowd.

She never gave an interview but was somehow well known to all of us, despite the fact that, by determined design, none of us ever knew what she was thinking. In a post-therapy world of oversharing, and amid the hurly burly of the 24-hour news cycle in which comment is an ever-flowing stream of inconsequence, she never expressed an opinion about anything.

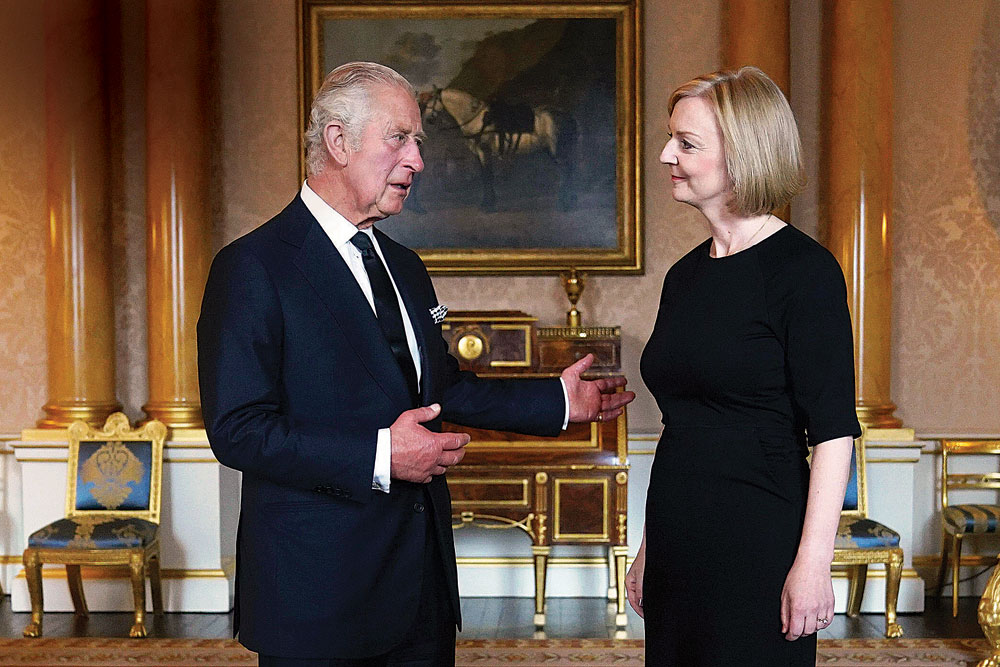

Most of us had never known another monarch. She sat atop the British pyramid of political, military, social and cultural honour for seven decades, during which she appointed fifteen prime ministers, the first of whom was Sir Winston Churchill, and the last, Liz Truss, she inaugurated only two days before her death. Who else in these islands has done work of national significance at the age of 96?

It is hard to exaggerate the respect she has commanded here. No one would be locked up for insulting our sovereign, but even prominent British republicans hedged their remarks with expressions of personal regard for her that suggested the revolution could be postponed for now.

But the departure of the most admirable member of the House of Windsor has left us bobbing aimlessly in the backwash of her pre-eminence, which was founded in a time we have lost, and grew into something of a kind we can never recreate. Whatever was left of Britain’s greatness may well have gone with her.

In post-Brexit Britain, the Queen was our last strong connection to a longer memory and the wider world. The shocking truth is that the newly installed Truss administration is the least experienced we have ever had. Of the holders of our four great offices, only the new prime minister has spent any time on the bridge of the ship of state, having recently served for just under a year as foreign secretary.

King Charles III will have to deal with a cabinet of small poppies, because Liz Truss, like Boris Johnson, has proved reluctant to promote experience and competence, preferring loyalty and ideological purity. So who will now personify the ethic of timeless public service that Her Majesty represented? Her longevity bridged the electoral cycle. Measured by her standards, every political project will now seem short-term.

Our political moorings are coming loose because our current crop of governing politicians revel in challenging received wisdom; the Truss administration has already declared its opposition to what it calls “Treasury orthodoxy”. One wonders what any monarch could do in the face of such callow confidence, given that the generally accepted role of the monarch has been “to advise, to encourage and to warn”. This amorphous role was capably filled by someone with the late Queen’s lived experience, having been the weekly confidante of fifteen premiers over seven decades. Will King Charles be able to provide any of those three services to politicians determined to push through the kind of fundamental changes to the state that Liz Truss has promised to bring?

No one doubts Charles’s sincere willingness to serve. He is widely touted as the best prepared king we have ever had. But experience is irreplaceable, and respect is earned, not given on demand. With the loss of the aura of permanence and restraint that the Queen so painstakingly acquired, the Crown’s function as a conservative backstop must to some degree be compromised. Most importantly, we cannot know what might happen in a confrontation between the unelected hereditary representative of the nation and an elected populist determined to enact radical change.

The ceremonial Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace has long been a spectacle for tourists, but what now will be changing, and what remaining in place? Can we yet appreciate what the late Queen did for our national culture, apart from giving her name to a railway line, a big ship and a famous rock band?

Before addressing that question, it is important to rid ourselves of the notion, popular in the conservative press, that we are somehow at the end of a “second Elizabethan age”. This is a patent absurdity. First, the notion that the reign of Queen Elizabeth II resonates with events of four hundred years ago is just silly. And the idea that her time on the throne represents any kind of historical, political or cultural unity cannot bear the slightest scrutiny. At the time of her coronation the world was led by Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin, there was rationing in Great Britain, we hanged murderers, and scarcely anyone owned a telephone. What kind of Elizabethan character unites The Beatles, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Stormzy, or James Bond, Mr Bean and Harry Potter? There is certainly a unifying narrative of decline—the end of Empire, the loss of heavy industry—and a constant theme of rising social equality, but neither had much, if anything, to do with the person of the Queen.

So how should we view her role in historical context?

WE MIGHT BE purely nostalgic and believe that her strength as a leader lay in representing all that was good in the Britain of her accession, that our bond with her was to live together forever in 1952. But her job, primarily, was not to reflect us back to ourselves, it was to perpetuate her own and her family’s position as rulers, and this she did very well. She took the best of what she knew and walked the easiest of paths with it. She changed nothing in private or public life that we can isolate and identify as her work. This explains how the monarchy succeeded in staying as it still is. The royals essentially camouflaged themselves in plain sight while encouraging us to believe that they were just like us. This was a political dead end, but a route to survival for the family. They used us and we followed them. They got status, we got stability.

Or we could take a hagiographic view and believe that she led and unified us by her exceptional example, by her unfeigned stoicism and endurance, by her personification of an ethic of service and selfless duty. In this reading, we used her to do uninteresting, repetitive tasks for us. Her reward was deference, while we were all free to run along and play as we wished while she cut ribbons, visited the sick, inspected the troops and handed out gongs. The royals were popular but dull—a recognition that most people never really wanted anything to change.

Or, with a rather more jaundiced eye, we might think that her function was to allow us to paper over the cracks in our national life in a way that was ultimately unhelpful, leaving us liable to fall apart as a nation without her. We depended on her for higher purpose, while she needed our approval, because in theory we could have removed her if we so wished. But we were more than glad to give her our support, in the name of continuity and of national self-esteem.

In this pessimistic view, both the royals and the public have been used by others for nefarious and selfish purposes. Her Majesty was no more than a glittering mannequin in the shop window, who was granted possession of her estate and trinkets while the real powerbrokers were left in the shadows to pursue their own agenda. Those manipulators then showed no duty of care; they simply exploited their unaccountable status to strip out much that was supporting the Britain of old. Our industries and public utilities have been sold to anonymous financiers and alien sovereign wealth funds, our foreign relations have been manipulated and our media distorted, with the result that our willingness to regulate the terms and conditions of business in this country is under serious threat. While we were hypnotised by the pageantry, our pockets were being picked. No one needs to believe that the Queen was complicit in this process; we only need to accept that now she has gone we are more likely to see the results of the deception.

In post-Brexit Britain, the Queen was our last strong connection to a longer memory and the wider world. The shocking truth is that the newly installed Truss administration is the least experienced we have ever had. King Charles III will have to deal with a cabinet of small poppies because Liz Truss, like Boris Johnson, has proved reluctant to promote experience and competence, preferring loyalty and ideological purity

Fifty years ago there was a standard examination question: Why has monarchy survived in Britain? Back then, of course, its survival seemed assured, and three good reasons sprang to mind. Monarchy played a useful functional role, the person of the monarch fitted that role perfectly, and no one wanted to embark on the arduous and uncertain task of replacing such a venerable institution. But how long will those reasons still apply?

If you want to have a constitutional monarch, try to find one like QE II—Britain’s greatest ever public servant. She spent almost all her adult life reading state papers for hours every day to make sure that she was as well informed as her prime ministers. None of them did that. She superbly fulfilled the requirements of a job that she didn’t expect to get and didn’t ask for. She understood the difference between royalty and celebrity, which some of her descendants and their spouses did not. She turned lack of imagination into a core political strength. She was essentially an ordinary person who grew into a great personage, grounded in a typically British desire to be intelligent rather than intellectual.

How kings and queens conduct themselves is vital to the survival of any monarchy, and Queen Elizabeth’s conduct was exemplary. There was real affection for her across public life, and indeed for her husband, Prince Philip, whose loss she was not long able to survive. Our unwritten constitution allowed her some scope to tailor her own part to suit her personal strengths, a slight liberty that she exploited without complaint. When she spoke, it was ever to voice the collective aspirations of her people, as with her broadcast during the Covid lockdown when she reassured us that “we will meet again”. Such mistakes as she made were small and were corrected forthwith, leaving her sans reproche, and as “a pattern to all princes living”, as her son reminded us in a recent address in Westminster Hall.

Her great cause, in some sense the lodestar of her public life, was the Commonwealth, an institution that she associated closely with her beloved father. She devoted an immense amount of time and energy to promoting and maintaining it and worked abroad so much that she preferred to holiday at home. Invisibly, she worked constantly as our most senior and effective diplomat.

Yet her legacy is inevitably mixed.

She was, as many have said, “the best of us”, and she has provided an admirable and clearly legible example for her successors to follow. But they will surely be more vulnerable than she ever was. Support for the monarchy is currently so inextricably tangled up with feeling for her personally that without her appeal the institution risks losing broad support. As it is, only 55 per cent of the population think that it is “very” or “quite” important for Britain to have a monarchy. That figure is not high and may well slide.

Great figures divert attention, fill gaps, and cast shade where perhaps light should be shone, so by her very stature she may have postponed or deflected some important and relevant questions, which have perhaps been left unattended for too long. We may find that it was largely her that united the four nations of the United Kingdom.

For good or ill, we shall never see her like again.

Also Read

The Power of Absence ~ by S Prasannarajan

A True Countrywoman ~ by writes Rachel Dwyer

Evaluating History ~ by Madhavankutty Pillai

The Queen’s Feast ~ by Shylashri Shankar

The Crown and India ~ by Kaveree Bamzai

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

From Entertainment to Baiting Scammers, The Journey of Two YouTubers Madhavankutty Pillai

Siddaramaiah Suggests Vaccine Link in Hassan Deaths, Scientists Push Back Open

‘We build from scratch according to our clients’ requirements and that is the true sense of Make-in-India which we are trying to follow’ Moinak Mitra