Why Modi is Still the One

Modi’s individual integrity gave the politics of hope a greater sense of authenticity

S Prasannarajan

S Prasannarajan  S Prasannarajan

S Prasannarajan  | 16 May, 2019

| 16 May, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Modistillone.jpg)

WE ARE LESS THAN A WEEK AWAY FROM THE verdict, which has already been imagined and reimagined by everyone with an urge to save/ redeem/restore/reinvent Indian democracy. This kind of frenzied anticipation, or dreadful foreboding, in abnormal times, presages the threshold moment of a country, and when our choice is between a perfumed life and a pathological lie. Is India there, or almost there? Is the change as mythological as the Hindu Rashtra built by masculine nationalism? Or, is it a prologue to the Hindu Armageddon as feared by the liberals repelled by the prevailing aesthetics of power? The India story on the eve of Verdict 2019 defies straightforward storytelling; the narrator, invariably, is an extremist.

The story, though, lies beyond both simulated alarmism and irrational adoration

And this is a story powered by an overwhelming protagonist who cedes no space to lesser characters. This is perhaps for the first time that one man dominates the story with such ease after Nehru and Indira Gandhi, but he is different. His backstory, unlike the First Family’s, is not marked by the privileges of birth or the grandeur of struggle—and, in retrospect, not even the unbroken support system of a party apparatus. In its singularity and in its defiance of linear moralities of politics, too, the story stood apart—and still does.

Narendra Modi is made possible by the power of ordinariness, and to this day, he is sustained by it. He is the product of the kind of popular impatience that makes democracies a battleground for both traditionalists and elites across the world today.

The impatience had its origins in the Nehru-Gandhi era that shaped the (official) intellectual identity of being Indian. The idyll of the secular state was a tribute to the New Man project of Nehru’s socialism. A bit of Soviet, a lot of Third World, a dash of Western enlightenment, and a pronounced rejection of nationalist and religious affinities—the Nehruvian Golem was preserved by an overzealous state. And there was nothing more sacred than the state.

The sacred state—where the citizen was given a code of conduct—had a long life. It supervised the social and intellectual life of India. It taught us how to read our past and it wrote the only acceptable history for us. Its secular ethos and institutional domination set the parameters of our intellectual life. It set the limits of our horizon. It told us what we are, and what we are not, lest we are corrupted by religious or nationalist instincts.

It gave birth to one of the longest serving political and cultural establishments in a democracy. And India was not just another democracy; its vastness and variety, its polyphony and plurality, made it too volatile to control. Still, the enlightened state—loftier than those who inhabited it— lasted for generations.

Its idea of Indianness curtailed any variation of civilisational memory, for the historically unverifiable past was a fantasy. Nehru was a scholar and a writer of great lucidity on India’s life as a country and as an idea, but the system he institutionalised as the nation builder gave little space for religious or civilisational expressions in politics. Such transgressions were anti-secular, which amounted to being anti-Indian then.

THE STORY WAS NOT as idyllic as it was made out to be. The anti-religious, secular politics of the Nehruvian vintage gave birth to the subcontinent’s most politically resourceful minority ghetto during the golden years of Mrs Gandhi. Secular condescension—a violation of the original Nehruvian ideal—was a rewarding political position. The ghetto provided the ballast that kept the official pretence of secular politics alive.

It was this double life of secularism that spawned the politics of Hindu resentment. When LK Advani rode that Toyota chariot, it was a journey into the deepest recesses of the Hindu grievance. It was grievance aggravated by the injustices of the present. The aggrieved Hindu took solace from the far shores of mythology and the vandalised sites of civilisation. Advani rode through the wounds imaginary and real. He literally paved the way for the empowerment of the Indian Right. The Nehruvian ideal, first betrayed by the ghetto builders of his party, was made redundant.

BJP in power changed the India of secular double life, and whether the party too changed accordingly is debatable. There was one thing that was undeniable: BJP has a greater capacity not to live up to the enormity of the mandate. It can reduce historicity to functionality. The redeeming factor then was the personality of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the reconciler of the Indian Right. He was the great communicator whose pauses were as eloquent as his words. He made politics a poetics of moderation, in spite of his ideological ancestry. In the end, that alone was not enough to sustain what history had unleashed. India indulged Vajpayee, not the party that failed to comprehend the impatience of India. The personal could not save the political.

It took another ten years. Maybe it didn’t. Modi’s struggle for power began more than a decade before 2014, in the last embers of Gujarat 2002. After the humiliation of 2004, the Right was in denial. The space still remained orphaned. Modi’s struggle took place beyond the general stagnation of the party; it was the lone struggle of a man for whom power was a moral system. He was not the candidate pre-ordained; he made himself inevitable, the only choice that mattered. When he stood there triumphant in 2014 after the longest campaign in Indian politics, he did not owe his victory to any charioteer. He was his own myth-maker.

The struggle did not come to an end with the attainment of power. The five years of Modi in power spawned multiple struggles—some epochal, others regressive. Amidst all that, only the harrumphers refused to see an India transformed— and the Hindu nationalist rearmed. We were repelled by the vulgarity of Hindu vigilantism, and rightly so, but we were also distracted by it. Out there, a cultural identity was reclaiming its place in the sun. The return of the Hindu adjective to redefine the national self shattered the secular consensus on which the sacred state was built. The easiest response to this resurgence was the liberal disdain that dismissed the shirtless of Hindutva as India’s ‘deplorables’. What happened in India after 2014 was not unusual. It happened earlier in varying degrees of cataclysm in other societies: when the man-made idyll was shattered by the raw force of history, old ghosts were certain to march out through the trapdoors. Whether the socialism was Nehruvian or Stalinist, the day after the fall was dramatic.

That said, Prime Minister Modi in his first term was not defined by the forces that sought legitimacy from his victory. There were of course instances when he should have spoken against the cruelties of Hindu vigilantism, and there were occasions when he should not have spoken at all. Still, the Modi of the last five years was not just a Prime Minister with a Hindu mission. The Hindu agenda needed a totem, and he became one by talking less about the mandir. The image that prevailed was of an overcautious moderniser. We wish he was less cautious.

The cultural argument was always problematic for the Right, and it was not different in Modi’s India too. The economic argument, though, was the Right’s to win. Not that India was ready for a Reaganesque or a Thatcherite Modi, but India was certainly ready for a conservative who could strike a fine balance between a bolder marketplace and an unbroken society. Modi could have been that conservative. He should be. What he did achieve was something unique: his individual integrity gave the politics of hope a greater sense of authenticity. In the age of fake salvation theologies, the young and the poor found in him an original. He redeemed the politics of poverty from socialism-as-usual.

Today, as he seeks another term, he is set against a disparate legion, whose cumulative idea of India is smaller than their mofussil minds. We still don’t know what is their argument beyond Modi. Perhaps that says a lot: Modi is the only argument that concentrates the political mind. The future will be a familiar place if Modi is given another term to become the bolder moderniser he was originally elected for.

Also Read

Other stories of General Election 2019

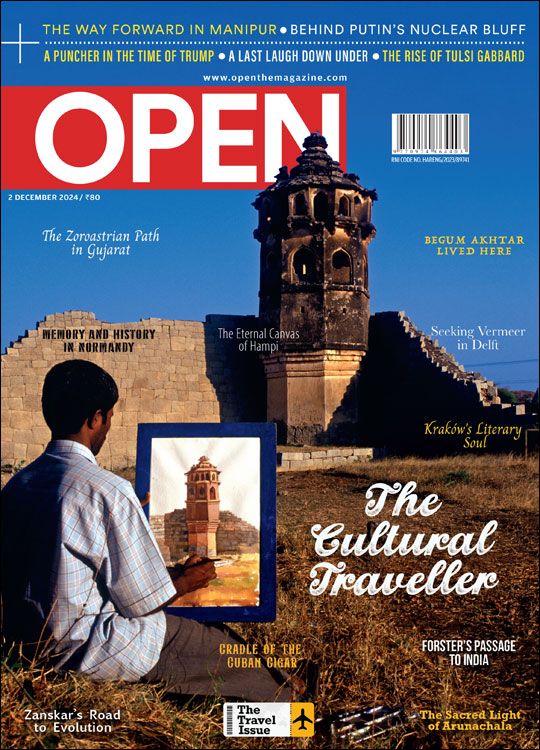

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Cover-Travel.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Sabarimala_0_0.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Photo1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Hindupolitics1.jpg)

More Columns

Upamanyu Chatterjee wins the JCB Prize for Literature Antara Raghavan

Lefty Jaiswal Joins the Big League of Kohli, Tendulkar and Gavaskar Short Post

Maha Tsunami boosts BJP, JMM wins a keen contest in Jharkhand Rajeev Deshpande