Inside South Kashmir, a Year after Burhan Wani’s Death

The Valley’s mad waters (Photos: Ashish Sharma)

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

06 Jul, 2017

|

06 Jul, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/JandK1.jpg)

THE SUN HAS come out in Kashmir after two days of intermittent rain, and in its luminosity, the anti- India slogans painted in bold letters along roads in Kulgam are clearly visible. Slogans against India and its security forces are not new in Kashmir. But in Kulgam and its neighbouring districts of Shopian and Pulwama, there are so many of them that it gives the impression of an area under siege. Like most of rural Kashmir, Kulgam, around 70 km south of Srinagar, is beautiful. With orchards laden with apples, vast paddy fields, lush green meadows, springs, and a tributary of Jhelum River flowing through it, Kulgam looks like a slice of paradise. But today, it is a place at war. In 2008, it was declared ‘militancy free’; in 2017, however, it would be suicidal for a policeman to venture out without protection. The orchards have turned into sanctuaries for militants—mostly local men in their twenties. In video clips and pictures shot on smartphones, they are seen smiling, eating food, offering namaaz, and fooling around with their guns. Many among their ranks are dead, killed in ones and twos in recent encounters with the police. They are poorly trained, but it doesn’t take much to open fire with an AK-47 rifle. A group of them did that on June 16th, killing six policemen in the closeby Anantnag district. They were led by a local militant commander, Bashir Lashkari. On July 1st, Lashkari, who dropped out of school after Class 3, was trapped in a house along with one of his accomplices and killed. A video circulated on WhatsApp groups afterwards shows him making meatballs for a feast. An AK-47 rifle by his side, he chuckles while talking to someone: “What do you know,” he says, “I am a cook.”

For the police, locating and ‘eliminating’ the likes of Lashkari is not all that difficult. The challenge, they say, is to shut what a senior police officer terms a ‘floodgate”—of young men getting radicalised and joining militancy. For that to happen, they say, it is important to press for law and order that spiralled out of control after the death of the militant commander Burhan Wani on July 8th last year. Ever since, this part of Kashmir has seen relentless violence by locals, many among who are now extremely radicalised. Egged on by militants and buoyed by lawlessness after Wani’s death, they have been coming out in large numbers to pelt stones at security forces engaged in operations against militants holed up in houses, helping them escape in many instances. Such mobilisations at encounter sites tend to happen quickly. Voice messages sent via WhatsApp urge people to come out in droves and foil operations. Dozens of these had to be abandoned over the past year in the wake of relentless attacks by civilian crowds. But now, the police have decided not to withdraw from such action at any cost, and wrest control from militants and their sympathisers. “The law and order problem in Kashmir is all militant-driven. And it will now be dealt with accordingly. There will be no let up,” says Munir Khan, who took over as Kashmir’s Inspector General of Police in May. The new security paradigm means that there are frequent encounters with militants, and that cordon-and-search operations take place almost every day.

In Hatipora, in Kulgam, a team of the police’s elite unit, Special Operations Group (SOG), and the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), led by the SOG’s head of operations in this area, enters an orchard patch for a SADO (search and destroy operation). Hatipora is a militant hotbed. According to the police, there are many drug addicts in this area who do not work at all and have turned into what they call ‘chronic stone pelters’. Such men are just a step away from becoming militants. Illegal sand mining is rampant, beyond which many locals in the area do nothing except indulge in violence against the police and aid militants, who use a section of the orchard as a transit route. Somewhere along the path is a ravine where they hide before venturing out.

The team enters stealthily, spreading out in a V shape once in. There could be militants inside, says the operations head. But after an hour’s search, no ‘contact’ with militants happens. “But that does not mean they are not around. So operations like these will continue,” he says.

Before the SADO, one of the police officers, in charge of a sensitive area nearby, had been playing a game on his mobile phone as he awaited the return of his bulletproof jeep that his men had taken for refuelling. The sound effects of the game were very different from the sounds he usually got to hear. He tried to smile as he spoke, though it did not come easily to him. There was a rawness about him, which he tried to hide behind the calm of his voice—even his “nonsense” and “bullshit” seemed measured, like a doctor telling a patient how he is going to use chemotherapy to kill his cancerous cells.

The man had not gone home for two years. He said he spoke to his son every morning before school. As always, he’d tell him he was busy—fighting a war he thought he and his colleagues had won long ago. But it had come back, and with a vengeance, after Burhan Wani’s death. This too shall pass, he said. He may live or die, he added, but the fight would go on. “See, I don’t care whether India gives me a medal or not,” he said, “I am a religious person and I am fighting a jihad against terrorism. I am a mujahid, I am a hero.” He was ready for the possibility of death, a thought that must have gone through his mind several times. “I will get replaced even before I am buried. Even my wife will replace me. Except for one’s parents, one is replaceable.”

When a local policeman dies in the line of duty, even his neighbours are reluctant to attend his funeral, says a non-Kashmiri police officer serving in the Valley

A SENIOR POLICE OFFICER who has served in both the state’s south and north often compares Kashmir to a tuberculosis patient who left his treatment midway because he thought he had gotten better. The ‘relapse’ had occurred before Burhan Wani’s death, the officer says. But this time, it seemed to be more vengeful. In 1990, when insurgency erupted in the Valley, the Indian state had slipped into a temporary coma of sorts. The local administration, including the police, had been rendered ineffective. But by the late 90s, the situation had been brought under control. By the mid-2000s, Kashmir had almost begun to look normal. The state police was at the forefront of this war, developing intelligence networks, conducting operations, getting killed in the line of duty. Many among the local population saw them as ‘traitors’ fighting militants for the ‘enemy’. “See, if I die here, I will be celebrated as a hero back home. But today, if a local policeman dies in the line of duty, even his neighbours will be reluctant to attend his funeral,” says a non-Kashmiri police officer serving in the Valley. The police manage to do their job, thanks to the likes of Constable Showkat Bhat, who died while rescuing a CRPF officer from a 2006 suicide attack on Srinagar’s Standard Hotel. The police have produced brilliant surveillance geeks like Sub-Inspector Altaf, nicknamed ‘Laptop’, who helped neutralise the Hizbul Mujahideen network in Kashmir—he died in a trap laid for him by terrorists in 2015. It was due to police efforts that many locals were weaned away from militancy. But mehmaani mujahid (foreign terrorists) took over the reins of operations; it is they who launched most attacks against security forces in the Valley, including suicide strikes. The last ‘big’ Kashmiri militant commander happened to be Hizbul Mujahideen’s Sohail Faisal, who was killed in an Army operation in 2006 in South Kashmir’s Bijbehara. He had spent around 15 years in Pakistan. After him, all field commanders in the Valley were foreigners. In 2011, Lashkar-e-Toiba’s top commander in the south, Abdul Rehman, was killed in a gun battle with security forces. A few weeks prior, Lashkar’s North Kashmir commander, Abdullah Ooni was killed in Sopore. Ooni was involved in several deadly ambushes against security forces and had established a strong base in Sopore. Five months later, the police also got his deputy, Abu Badr.

In 2015, another dreaded Pakistani terrorist, Abu Qasim was killed in an encounter with the police. Qasim was a part of the Lashkar squad that had carried out an attack in 2013 on an Army convoy in Srinagar’s Hyderpora in which eight soldiers lost their lives. He was killed three weeks after he had laid the trap that killed Altaf ‘Laptop’.

But while the police were trying hard to contain militancy, the Kashmiri leadership only seemed interested in playing politics. In 2002, after Mufti Mohammed Sayeed became Chief Minister, he spoke of disbanding the SOG. He said that people were tired of barricades and crackdowns and they required a healing touch. “Which was all right,” says a senior police officer, “except that in the process, a message was conveyed as if the police force were the state’s illegitimate child.” The SOG continues its work even now, but more like a kind of phantom force. Senior police officers speak of their helplessness when men serving in the SOG come to them and say that they feel like orphans since they are not even supposed to take the name of their unit. “It is a shame. Police from states like Gujarat and Maharashtra have come here and learned from us. But we are supposed to use faux names such as ‘task force,’” says an officer who has served with the SOG. “The irony is,” says another officer, “we are all SOG in the sense that we have to work like them; otherwise we can’t win this war.”

The hypocrisy is evident in how some politicians who cry hoarse over the SOG’s existence demand that only its men be assigned to their own security. “In their uniforms, the SOG personnel look more impressive and deadly,” says a senior police officer. Another officer remembers how the wife of a senior minister thrice requested a change of guards at their house. “When it happened the third time, I called her and asked her the reason. She said: ‘I am very scared of local boys; will you send Hindu boys from Jammu?’” he recalls (SOG has men from all over the state).

It is the same hypocrisy that resulted in the police taking a step back after current Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti said in a statement after Burhan Wani’s killing that it would have been better had he been caught instead of shot. “Here we are, engaged in deadly combat with militants, and she tells us what we should have done,” says a police officer.

Senior policemen speak of how a collective failure of all state organs enabled militancy to be revived. They point at how laws turned ineffective when it came to dealing with militant sympathisers

It is this chameleon politics that has resulted in a surge of violence in the state’s south. Police sources say that after Mufti Mohammed Sayeed came to power in alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2015, they came under pressure from the government to halt anti-militant operations. “It came to a point where we were told that the militants don’t trouble us, [so] let us not trouble them,” says a senior police officer. The political interference resulted in the removal of security pickets at crucial points between villages and localities in the south, which is a stronghold of Sayeed’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP). “Once a bunker is removed, it is not easy to put it back,” says the officer.

The officer who has served in the south says all the young males he detained for stone pelting had accessed Islamic State’s online magazine Dabiq on their cellphones.

The situation took a dire turn after Wani’s death. Security forces even stopped venturing into some areas, leave alone conducting operations. “In Kulgam, operations have resumed almost after a gap of 18 months or so. In Shopian and Pulwama, the situation was more or less the same. Imagine the time we lost,” says the officer.

Senior police personnel speak of how a collective failure of all state organs enabled militancy to be revived. They point at how laws turned ineffective when it came to dealing with militant sympathisers in these areas. “I would arrest a stone-pelter, only to watch him be set free after ten days. Sometimes we got so frustrated, we would ask the judge to at least book him on charges of eve-teasing so that he stays in jail for slightly longer,” says an officer.

The police lay out the following trajectory for militant sympathisers turning into militants: out of sympathy, the man begins to first pelt stones. When the law fails to check him, he gets emboldened and becomes a chronic stone-pelter. Sources say that militants keep tabs on such men and approach them to join the militant fold. In the last few years, the law has failed to prevent this. For instance, a stone-pelter is supposed to sign an executive bond in front of a magistrate which makes it binding on him to pay a fine if he repeats his offence. But for repeat offenders, this was not being followed at all. The police cite the example of Tauseef Wani, a 28-year-old man who was killed during clashes that broke out in Pulwama to save two militants hiding in a house on June 22th. Tauseef died due to a direct hit from a teargas shell. He was detained twice in 2010 and 2016 for stone pelting and had ten cases registered against him. But he never stayed in jail for more than six months. “The main dilemma is ‘What are we?’ We keep oscillating. Are we here to fight militancy or behave like the hospitality and protocol department of the state?” asks a senior police officer.

Now, in Kulgam, the police have started using Bad Character Surveillance Act, which gives quasi-judicial powers to district police chiefs against stone-pelters and militant sympathisers. Once booked under this law, an offender has to disclose his movement outside his village, any violation of which lands him in jail. “It has worked well so far,” says Shridhar Patil, Kulgam’s superintendent of police, “we even had families approaching us whose wards were drug abusers and pelted stones. We have sent two such cases to the de-addiction centre in Srinagar.”

The police will also very soon make its writ run large by putting up posters of wanted militants next to every anti-India slogan on walls and shop shutters. “The new militants have no central command. They are more like criminals who engage in senseless violence. They are facing a crunch of weapons and money, and we will catch up with them all in the next few months,” says Swayam Prakash Pani, South Kashmir’s deputy inspector general of police.

The police are now finally gaining an upper hand. But somewhere in the middle of this war, there is also anger among the police at how the Indian state is treating them. Since 1989, the Union Home Ministry has spent over Rs 4,596 crore under ‘Security Related Expenditure’ (SRE) on the Kashmir Police. But till the killing of six policemen on June 16th, many police stations in the south did not even have bulletproof vehicles (they have been promised now). “Those who are prepared to die for India’s flag are treated shabbily even by the Indian state,” says a police officer.

The state policemen have no parity at death with a jawan from a Central police force. There are hardly any medical facilities for him. Senior police officers rue that if one of their men gets injured, he cannot even be sent to the local hospital, as he may get lynched there. If he has to be sent outside Kashmir for the treatment of grave injuries, it is a time-consuming process: the district police chief has to write to the police headquarters, which then writes to the health department, which must then seek the advice of the state home department. The police have long been asking for at least two trauma centres, one in the north and another in south. “There have been times when we have spent money from our own pockets for the special treatment of injured policemen,” says a senior police officer. An SOG head constable Open spoke to takes home a salary of Rs 38,000. He has served for 20 years and has taken part in most of the encounters against militants in the last few months. He gets a risk allowance of Rs 70. “Special police units working in insurgency areas all over India get at least 40 per cent extra as a salary component. In Kashmir, we get nothing,” says a police officer. Many policemen expressed their resentment in June when they were asked to contribute a day’s salary to a martyrs welfare fund. “Are we mercenaries?” asked a policemen posted in district police lines in Srinagar, “it is the government’s duty to ensure our welfare.”

Police sources speak of how SRE funds have become the ‘oxygen cylinder’ for the state and how many have invented brazen methods to access this money. Last year, the police decided to stop renting 20 huts on the Amarnath Yatra route as they usually did every year for their senior cadre. “We were gheraoed by the staff of Jammu and Kashmir Tourism Development Corporation who said they had not even been paid salaries since we did not take the huts on rent,” says a police officer. He gives an example of how SRE funds are misused: a man joins a political party and then approaches his district police chief for security. He is provided with two special police officers (SPOs). Then he says he has no place for them, so the police construct an outhouse in his property for his SPOs. After a while, he disconnects his own electricity connection and begins to draw from the outhouse, which gets free power from the government. After a while, he goes to the district commissioner and says the SPOs have damaged his property and asks for a rent assessment. Then he starts getting paid for the space given to SPOs.

In 2006, according to a police source in Pulwama, the then district SSP asked one of his deputies to call all men he had at his disposal. The next morning, he found only 12 men waiting for him. The source says the SSP drove in his car to the boundary of his district, followed by a Tata 407 truck. From there, he made a U- turn, picking up police guards from spots where he thought they were not required. He found that some guards had been posted on bridges. For the night, they would go to accommodations next to bridges which they had rented for which the government was paying. By the time he returned to his office, the strength of men had increased from 12 to 50.

In North Kashmir, thankfully, the situation is much better. Here, the number of foreign terrorists is higher than local militants. There are about 70 Pakistani terrorists while the number of locals is only seven. “We don’t let them rest here,” says Imtiyaz Mir, SSP, Baramulla. “They are under tremendous pressure to turn North into South. But we are taking cognisance of every small matter,” says Nitish Kumar, IGP, North.

IN THE RAIN, Srinagar city looks worthy of a dirge. On the road from the airport, paramilitary soldiers stand on duty; in their raincoats and knee and elbow pads, they look like scarecrows. Everyone appears on edge all the time. When they get stuck in traffic jams, the soldiers standing with their machine guns atop trucks become more alert. On FM radio, a woman caller calls a cleric, asking him if it is okay to lie down after breaking a Ramzaan fast at iftaar. Sirens wail past as the muezzins call from mosques. There is a cement ad which speaks of a ‘mazboot buniyaad’ (strong foundation) for Kashmir and then breaks into an ad for a dialysis centre. Local newspapers are full of patients requiring critical treatment for various diseases, mostly kidney failure.

A young girl, from top to bottom in an abaya, steals a conversation with a boy in school uniform half hiding behind a tree. Under her grey overalls, the girl wears shiny red sandals. An apparently mad man, of which there are many in Kashmir, looks at them and mumbles. A senior cop in north Kashmir calls it the phenomenon of maet aab—of the mad waters of Kashmir. He narrates a story of how a husband asked his wife not to drink water from the river the next day since doing so would turn a person mad. But the next morning, everyone around them had consumed that water and gone mad. In that madness, they attacked her. In a moment of desperation, the husband advised that she drink the water too and turn mad.

It is this madness with which a crowd caught hold of a police officer at Srinagar’s Jama Masjid and lynched him. Police intercepts of militant calls shows them speaking calmly about cordons outside and how they are prepared to meet what is destined for them. The same madness makes some believe that the 2014 floods came because a family in the city’s posh Rajbagh locality insisted on celebrating the birthday of their dog.

The police officer who has not been home for two years says it is all “nonsense” and “bullshit”. He says the game in Kashmir is one of respect and honour. “When the youngsters realise there is more respect in being a policeman than a militant, they will opt for the police,” he says. “How will that happen? When one of us dies, let my DGP lead the procession. It will all turn from that moment.”

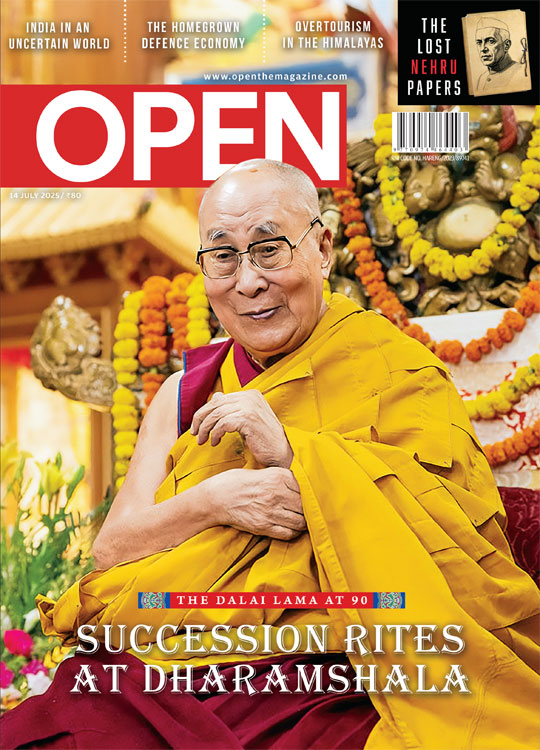

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

‘We build from scratch according to our clients’ requirements and that is the true sense of Make-in-India which we are trying to follow’ Moinak Mitra

Gukesh’s Win Over Carlsen Has the Fandom Spinning V Shoba

Mothers and Monsters Kaveree Bamzai