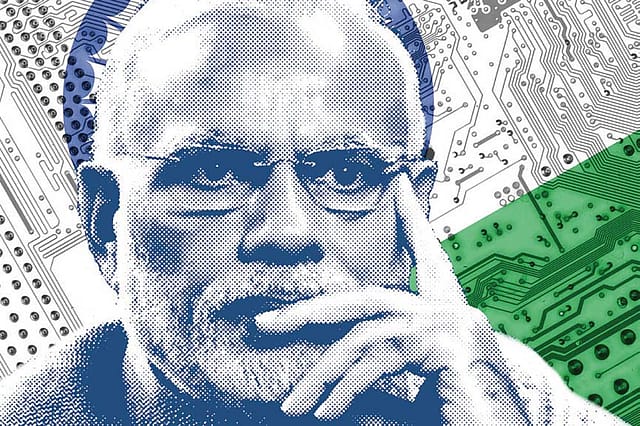

Narendra Modi and the Idea of Innovation

IN A COUNTRY like India, documentation of innovations in governance has two important dimensions. Firstly, as society, it is important we take our innovative thinking to the next level from what has been famously described as jugad! Ideally, it connotes an ability to invent solutions through simple means. But over the years, it has also acquired a bad name, as many perceive jugad as an art of overcoming obstacles by bending rules as also hoodwinking the system. With true innovations getting due respect, inclination for this kind of jugad may diminish, bringing greater scope for a genuine urge to find lasting, respectable and replicable solutions. Prime Minister Modi has recognised the importance of inculcating the culture of innovation from a young age. To this end, the government's Atal Innovation Mission is setting up Atal Tinkering Labs in schools across India, equipped with the latest tools and technologies of science and design to expose India's next generation to ideas beyond textbooks. After all, it is this generation which will make the twenty-first century India's century.

Secondly, innovations in governance become more important when they make systems deliver, ensuring that welfare reaches the unreached. In yet another innovative break from past practice, the present government has nudged those at the cutting edge of delivery of government services to come up with new solutions to entrenched problems. Instead of constituting groups of ministers, Prime Minister Modi has focused on creating groups of secretaries and groups of bureaucrats at other levels, so that the machinery ultimately responsible for implementation cuts across silos and finds innovative solutions. An intense urge to make the system deliver comes out of sensitivity towards the deprived. It is, therefore, obvious that innovations resulting in greater benefits to the marginalised need more attention. To that end too, this kind of documentation of innovations in governance has its own importance.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The innovations dealt with in this book are diverse in nature. A few of them could rightly be described as institutional innovations. Several have a clear objective of bringing greater transparency and accountability. While a couple of them are about celebrating our culture, others have an essential element of ensuring social justice in a more effective manner. But, a majority of these innovations are aimed at, using the term used by the Prime Minister, 'ensuring greater ease of life for the countrymen.'

IT IS RARE for prime ministers to delve deep into the nitty- gritty of project implementation and monitoring. For Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it's routine. The history of governments in India is littered with good intentions and faulty implementation. The buck of government stops with the prime minister. And Prime Minister Modi takes his responsibility seriously to ensure timely implementation of projects.

Every month, since March 2015, the Prime Minister conferences with the cutting edge of the government's implementation machine consisting of secretaries of various ministries and departments and chief secretaries/administrators of India's twenty- nine states and seven union territories (UTs). Over an hour or two, he directly addresses a wide array of public grievances, reviews key infrastructure projects and scrutinises the implementation of programmes. This is PRAGATI, or Pro-Active Governance and Timely Implementation, a radical innovation which imparts much momentum to the usually slow business of governance.

PRAGATI takes coordination among ministries, central government departments and state governments to a whole new level. Through a combination of videoconferencing, digital data management and geospatial information systems, it enables the PMO to track the progress of central and state government ventures in real time, with current information on the ground-level situation and the latest visuals. For their part, officials are able to exchange information and discuss bottlenecks and work out how they can be addressed, often in advance of the meeting. The pressure of direct accountability to the Prime Minister delivers results.

The system makes for transparency and accountability and is in keeping with the spirit of cooperative federalism. It brings state- level officials face to face with central government secretaries and the PMO, thereby allowing tripartite, no-holds barred dialogues on how to tackle issues of implementation and delivery. It cuts through the complex, multi-level decision-making mechanism and reconciles the conflicting priorities of stakeholders.

Consider the setting at one of the early PRAGATI meetings. Prime Minister Narendra Modi's digital image dominates the conference room, where senior officials of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) have gathered to discuss the Kishanganga hydroelectric project in Bandipora district. Chief Secretary Braj Raj Sharma and his team are in suits and jackets; Srinagar can be bit nippy in late September. The Prime Minister is in his trademark 'Modi kurta', as Delhi is still too warm for long sleeves.

Ten analogue attendees are grouped around a table with the Chief Secretary at the head, directly facing the Prime Minister. Another ten participants are digitally present, sharing the screen with him. It is 2015 and the Prime Minister is keen that the Kishanganga plant be commissioned without any delays. So far, the project has had a rough passage, with Pakistan having sought to stymie it by petitioning The Hague, but India managing to carry on.

Describing the status of the 330 megawatt (MW) project, the Chief Secretary tells the Prime Minister that all but three of the 382 hectares required have been acquired, which involves displacing 185 families. The plan drawn up for their resettlement and rehabilitation was unfortunately found 'unsustainable' and has been revised. The Prime Minister tells the power secretary to coordinate with the J&K government to expedite the project, while paying particular attention to comfortably resettling the displaced population.

Kishanganga was one of the many projects which received a gentle prod from the Prime Minister at the sixth PRAGATI meeting on 30 September 2015. Face to face with the Prime Minister, officials across the country found themselves responding directly to him on projects under their purview.

INVEST INDIA IS a unique entity, in the way it is structured and in its mandate. It is not a government department or agency or even a central public sector enterprise. Instead, it is a not-for-profit company jointly promoted by the central government and the private sector, represented by apex industry chambers—FICCI, CII and NASSCOM. The government represented by the Department of Industrial Promotion and Policy holds a 49 per cent stake while the private sector chambers hold 51 per cent in equal 17 per cent portions. However, the entire funding of Invest India comes from the Government of India. The chairman of Invest India is the secretary, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, while the managing director and CEO have been recruited from the private sector.

This corporate structure is critical for the efficient functioning of Invest India. The corporate structure enables it to do its unique and important job, which is to provide end-to-end solutions for potential investors, from the pre-investment stage which may involve scouting for land and liaising with the central and state governments, as also their relevant agencies; to the investment stage of gathering the necessary approvals to commence operations; to a post-investment stage which may require the settling of any grievances with any agency or government. Government agencies and public sector enterprises are governed by detailed, complex and sometimes counter-productive sets of rules and processes. Invest India has a nimbleness in functioning that a purely government entity would not.

The case of Peugeot highlights the nimbleness of Invest India in its mission. In August 2015, officials of Invest India saw an article in London's Financial Times which had a story on how Peugeot was considering three countries—Morocco, Iran and China—as a destination for an almost 400 billion Euro investment. Invest India decided that it would make a pitch for India which was initially met with a lukewarm response since the company had left India in 2005 after a disappointing run. It would take a visit to the Paris headquarters of Peugeot to make a dent. While in Paris, it was evident that the other destination countries had offered sweet incentives for Peugeot. China and Iran were offering fiscal incentives in the form of tax breaks while Morocco was already home to a big Peugeot factory. Invest India could offer no fiscal incentives so the presentation focused purely on market opportunity in India and how that would transform the then financially stressed carmaker's fortunes and valuation. The presentation provided a breakthrough but did not seal the deal. Morocco added to their offer by promising to pay the transportation cost of every Peugeot car made in that country. Invest India had to respond without any monetary incentive. And it did. A factory in Chennai that was used for manufacturing by Hindustan Motors was defunct and under the Bureau for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction. Invest India's team did the necessary work to offer this ready-made factory (along with land) to Peugeot. By June 2016, Peugeot was on board along with its key supplier. The French carmaker will not just manufacture cars in India but will also invest extensively in research and development. In August 2015, India was not even an option.