Modi is Pretty Impressive, says Francis Fukuyama

One of the world's most influential public intellectuals discusses the state of the world with Open

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

|

25 May, 2017

|

25 May, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Fukuyama1.jpg)

On the day after Donald Trump sacked James Comey, his FBI director, I interviewed Francis Fukuyama, an American political scientist who has for decades been a source of wisdom (and occasionally of controversy) on the state of the world. The author, most notably, of The End of History and the Last Man (1992), Fukuyama is currently a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and director of that institute’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law. I had last met Frank— as he’s known to his friends and colleagues—in 2007, and he appeared not to have aged at all. Unchanged also was his impressive—and essentially Japanese—courtesy. He is a quiet American, and there are few better people to talk to if one wishes to comprehend the current global shambles.

The Middle East is a violent mess, as always—only more so, and is exporting its violence to foreign parts. Russia has become a malign force in global affairs, adding interference in foreign elections to its repertoire of misdeeds.

China is pushing hard—and stridently—to be an alternative to the United States as a global superpower, without any of the democratic aura that America has, and with a hard-edged hegemonic impulse that would appear to brook no opposition. Europe is rudderless and fragmented, a continent struggling with the unraveling of its union. India and Japan are peripheral: India by virtue of its lack of ambition and its self-diminishing obsession with an antagonistic neighbour (Pakistan); Japan because of a demographic crisis that exacerbates every aspect of its innate conservatism and insularity.

But most disconcerting of all is the part that the United States appears to play in this mess. Under a president for whom few outside America’s Red states have genuine respect, the most powerful country in the world is in the throes of a major national redefinition. It does not help that President Trump is so mercurial: what he says one week he unsays the next. Without the United States as a strategic and moral compass, the world is in terra incognita, unsure of where it is going, and of what horrors lie around the corner.

Fukuyama had said in The End of History that liberal (Western) democracy had won the great ideological argument over which political system was best. After all, the Soviet Union had collapsed. In the years since the book’s publication, critics, many of whom have not read it carefully enough, have taken pleasure in kicking him in the shins. His book’s title, while eye-catching, made him a target for easy, lazy barbs. Fukuyama has stressed all along that his point was that the idea of liberal democracy had won, and not that the world would, somehow magically, become liberal and democratic. As he wrote, ‘At the end of history, it is not necessary that all societies become successful liberal societies, merely that they end their ideological pretensions of representing different and higher forms of human society.’

He was (and is) right. No one seriously argues today that communism offers an alternative to liberal democracy. Islamists contend that their way is better, but theirs is a method rejected, even by the majority of the world’s Muslims. What we do have, however, is an erosion of democracy even within those countries that are democracies. The form is intact, perhaps, but the substance is reduced. In some places—Turkey, for instance (which we would never, by any definition, describe as a liberal democracy)—the substance has become the form. Holding an election is all that matters, the fairness of it all be damned. Putin, too, in his claims that he was elected, is paying Fukuyama a perverse compliment: “We couldn’t beat them, so we joined them… on our terms.”

This is the world we live in, and about which I talked to Frank Fukuyama.

I’d like us to have a freewheeling conversation about the state of the world.

The world’s pretty strange these days. I’m just saying.

Stranger than usual?

Much stranger. I would say that more has happened in the past year of an unexpected nature that was unanticipated, at least by me and most of the people I know, than in the previous 20 years.

Were these things that you couldn’t reasonably have been expected to anticipate?

I thought, ever since the 2008 financial crisis, that it was strange that there wasn’t more populism in the United States. That crisis, in retrospect, was really important because it was something that was engineered by the elites and it hurt ordinary people, and then the elites managed to largely shield themselves from the consequences. The last time this happened, in 1929 to 1931, you had this big populist revolution and the New Deal, and all that anger was channelled in a way that led to big, fundamental changes. Why wasn’t that happening after 2008?

In fact, the part that I didn’t anticipate was, first, that all that energy would go to the Right rather than the Left, and then that the Right itself would take off in this Donald Trump direction. That I really didn’t see. I would have anticipated someone like Bernie Sanders doing much better than he actually did, although he did pretty well in many respects.

Trump is really a one-of-a-kind politician…

Every time you think you’ve got him pegged, he changes. As of about two weeks ago, I was thinking, “He’s actually proving to be just a conventional, really conservative Tea Party Republican.” If you look at all of his appointments, and you look at the actual policies, China’s not a currency manipulator anymore, we’re going to keep NAFTA, we’re going to keep the EXIM Bank, no trade wars in the immediate future. Then he goes off and does and says things that make you think that he’s still off in la-la land, the latest being firing [FBI director] James Comey. I don’t know what to think at this point.

Is he off in la-la land? Nuts? It’s a perfectly reasonable question.

Right from the beginning I thought that he was just the worst possible president you could imagine. I don’t think he’s got remotely the kind of character that you would want as a president. He’s not thoughtful. He’s not informed. He’s not a person who is uninformed but realises that he’s not informed, and therefore thinks that he’s got an obligation to inform himself. He’s extremely vain. He’s preoccupied with himself at the expense of virtually any other value. He’s never shown the least interest in public service or some larger conception of public good that didn’t somehow immediately add to his wealth, or his notoriety.

It just seemed to me very hard to imagine that a person with that kind of personality could make a good president because not only do you want the president to avoid the many kinds of vices but you want him to exhibit certain virtues so that your children can look up to him. He seems to have absolutely none of that.

Those character flaws get in the way of any kind of coherent articulation of a policy. As far as I can tell, why did he strike Syria? Ivanka saw something on television and she didn’t like it, and she said to her dad, ‘We can’t allow this,’ and so, okay, we can’t allow it.

Do you see no virtue in him at all?

I can perfectly appreciate why he’s popular. There is way too much political correctness, especially on university campuses. There are individual policies I like. I like the populism much better than the Tea Party version of conservatism, that you care what happens to your working class rather than simply trying to strip benefits from them and drive down their wages and so forth. I like his infrastructure ideas. I think that the deregulatory agenda is a good one. There are individual things that he’s done that I approve of. I just think that in most of those cases, either he’s doing them for the wrong reason, or [he] doesn’t have the skill to actually bring them about.

As a man who’s written about the world for much of your academic career, are you in despair about Trump’s view of the world?

I have two attitudes. As a citizen, yes, I wake up every morning shaking my head and screaming inside, “I can’t believe he did this.” But it’s been interesting as a political scientist to watch this because you have all sorts of theories about the way politics is supposed to work. The main theory that’s being tested right now is about American institutions. They are designed to prevent a person like Trump from doing too much damage, and so we’re now going through a living experiment, a real-life experiment to see whether these institutions are functioning properly or not.

The Comey firing is going to be a test, because this is the first moment in which Trump has actually taken a decision that has a big institutional impact. If the institutions are working properly, he shouldn’t be able to quash an investigation of himself and his friends in this fashion. We’ll have to see whether he gets away with it or not.

Populism isn’t just American. We see it everywhere. What’s going on?

I don’t mean to sound academic about this but it’s really not one phenomenon.

In northern Europe, it seems to be similar to what’s going on in Britain and the US, where it’s older people, the working class, the less-educated people [who have been] left behind by globalisation. In southern Europe, all the energy is going to the Left rather than Right-wing parties, with Syriza and Podemos in Greece and Spain.

They are economically populist but they’re not anti-immigrant and xenophobic. In Italy, it’s a really weird thing because the Five Star Movement, their populist movement, is actually an upper middle-class party. A lot of their supporters are professionals, doctors and lawyers and so forth. Again, that doesn’t match the paradigm in any other part of Europe.

How should Europe handle Brexit?

I usually have pretty strong opinions about a lot of things but not that one. I guess I’m sympathetic with those Europeans who want to not make things very easy for Britain because the Brexiteers want to have their cake and eat it too, and I think that’s not a good precedent to set.

I do think that the EU, as a political unit, has got some very deep problems. Its problem is weak institutions. The Euro was clearly a big mistake. They’ve really not been able to deal with that in a serious way. I think the Schengen system also does not work because they don’t have secure outer borders. That’s going to come back to haunt them. Right now, there’s a lull in Syrian migrants, but the whole of sub-Saharan Africa’s going to empty out into Europe unless they secure that border, and that politically is just not tenable. I think it’s more a failure of German leadership than anything else but they’ve really not been able to address these problems.

What about populism in Asia?

Populism expresses itself completely differently in Asia because either it’s Left-wing populism like the new President Moon in [South] Korea, who represents a popular movement out on the streets that got rid of Park Geun-hye, or it’s controlled by the government, as in China, where I think Xi Jinping has been stirring up—and then benefiting politically from—the anger that a lot of ordinary Chinese feel about this very corrupt party elite. It’s one party elite using populism to attack another party elite.

As for Duterte in the Philippines, I don’t know where that comes from. That really is sui generis because he doesn’t represent a big movement in the Philippines. He just seems to be this one wacko guy who just started shooting people in Davao, and then took it national.

A ‘Dirty Harry’ became president.

Yes, right.

Have you thought about India?

I’ve thought a lot about India. I don’t think there’s a universal crisis of democracy because I think a number of democracies— Australia, Canada and New Zealand—are going well. Germany’s doing well, and Scandinavia. There are certain democracies that are not doing well for a common reason: the United States, Japan, India and Italy. In all four, the central problem is weak government. Basically, governments reflecting divided societies that cannot make big, important decisions for the common good.

The previous Congress Government in India was exhibit number one. You can see this in things like infrastructure where India, compared to China, is falling way behind because the Government simply could not decide to build the airport or the road or the electrical system. I think the reason that Modi won by such a large majority is that Indians were just sick of it. Their Government was not producing results, and they wanted a strongman that could actually do stuff. Now they’ve got one.

During his first year, I kept thinking to myself, ‘He’s not delivering, really, on his promise of actually strong leadership.’ But now I would say it’s pretty impressive, both for good and for ill. For the good part, in terms of economic reforms, the GST reform is pretty hard to pull off. You’ve got how many states in India, 29? All of them have to agree to this thing. And demonetisation was mind-boggling, that you’d basically confiscate the cash of 1.1 billion people. That may be not that hard to pull off, but surviving that politically is really impressive, and he seems to have succeeded in doing that.

The Aadhaar system also took a fair amount of capacity to get running. I guess I’ve come to feel that I have to re-evaluate my view of the Indian Government because it’s been more effective than I would have thought. I think that Modi, like Abe in Japan and Trump, reflects an unhappiness of voters with weak and indecisive democratic governments, and a yearning for somebody who’s going to cut through all the nonsense and get things done.

Now, the downside. This is based on a massive shift in India’s national identity. I think one of the really good things about Indian democracy since Independence has been that you’ve had basically a liberal concept, what Sunil Khilnani called the ‘idea of India’. I think that’s the only way that you can get such a diverse society to live with one another. The BJP wants to shift that sense of identity to a much more specifically Hindu one. I just think that that’s a formula for endless conflict down the road. I think the good aspects of strong government are coming together with some more disturbing ones.

If you were a young Indian today, what sort of future could you expect for India?

I think it would be very good if India returned to being a model of a successful liberal society—in which you have this incredible diversity but nonetheless is a coherent political unit that has a government that can make decisions, and do things for the common good, and set the groundwork for continued economic growth. I guess that would be a very positive vision.

I think the bad vision is that it succumbs to this populist nationalist trend, and wants a strong government just for the sake of a strong government based on a narrow concept of national identity that excludes really important parts of its own population.

Can the world learn to live with an aggressive China?

No, I think that’s going to continue to be a big problem because China is reshaping the whole global architecture. I’ve felt for a long time that the bigger, long-term threat to global order is China, not these jihadists in the Middle East, because they’re so much more powerful.

They’ve got a country behind them. The reason that jihadists shoot up people in a theatre or a café is that they don’t have any other ways of affecting anything. It’s dramatic but also pathetic. The Chinese will be larger than the United States economically if they don’t hit a really big roadblock. That’s going to happen in another decade.

Already, the fact that they’re such big net savers, as opposed to us being net debtors, allows them to do stuff that we simply can’t do. They want to sanction South Korea for putting up a new air defense system. They can use their economic might to do that. We’re only at the beginning of dealing with the rise of China as a great power.

Asia is probably the part of the world where I’d worry about overt military conflict. Right now, it’s more critical on the Korean peninsula but I think the South China Sea is still a big flashpoint that could lead to a serious risk of war. You also have this very chaotic situation in Northeast Asia in which America’s two democratic allies, South Korea and Japan, are more at each other’s throats than they are dealing with this common problem of a rising China.

Do you see conflict between India and China?

I think that their interests are basically not aligned. Over the last two decades, India has shifted from basically neutrality or leaning towards the Soviet Union to a much more happy embrace of Washington, simply because the United States is the only country that can really balance against China. The US has reciprocated to some extent in terms of accepting India as a nuclear power. I do think that there is going to be this continual rivalry, and it plays out in a lot of the stuff going on in the Indian Ocean in terms of access to naval facilities and who’s patrolling in what parts of the ocean.

What about the Chinese people themselves? Might they ultimately be the solution?

That’s been the hope. This is standard modernisation theory, that as you get richer you get a middle-class that wants more political participation. They want to protect their property rights and so forth. That has unfortunately not worked out in China so far. They’re already at a level of per capita income where that should have kicked in. They’re basically where Taiwan and South Korea were in the 1980s, when they had a middle class that led to democracy in those two countries. I don’t see any evidence that it’s happening in China. As far as I can tell, most middle class people in China are actually not that unhappy with their current government, and above all, I think they still have a memory of instability. They do not want to do anything that’s going to upset the current growth machine.

I think that if you’re going to get pushback against the regime of a serious nature, one of two things has got to happen. Either there’s a serious split within the Communist Party, which could happen because Xi has really pissed off a lot of people within the party, and a lot of them have guns, and they’re very unhappy, so there’s this ongoing debate about whether he can step down after 10 years, because he can’t just retire into the sunset like Hu Jintao. He’s made way too many enemies. That’s one issue.

The other issue is that they have a big economic setback, that there’s a financial crisis leading to recession, which they’ve never had since 1978, where people are losing jobs, and the government doesn’t seem to be so competent and in control. You can imagine a lot of sudden, mushrooming discontent. I suspect that’s bound to happen at some point.

There’s also no guarantee that a democratic China will be less aggressively nationalist.

No. That’s one of the disturbing things. I go to China pretty regularly, and on the domestic issues there really is a liberal middle- class layer. But on foreign policy, it’s really different. There’s a huge amount of nationalism, and a lot of pent-up resentment about China not being treated fairly and respectfully. I do think that a democratic China could actually be more nationalist in certain ways because the politicians are going to have to compete for votes, and one of the ways of getting them is by demagoguing on nationalist issues.

Can you imagine a Chinese Trump?

That’s really scary.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

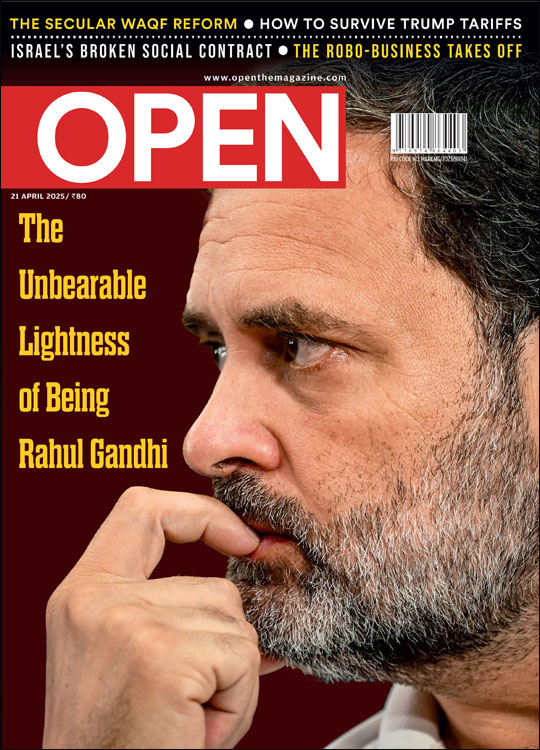

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Ukraine silently encroaches on ‘friendly’ Moldova Ullekh NP

NFRA chief Ajay Pandey joins AIIB Rajeev Deshpande

The Revenge of Roughage V Shoba