IN 1993, AFTER THE Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party came together in Uttar Pradesh, a slogan floated to celebrate that alliance did not come as a surprise to the Sangh Parivar. A state where people had brought down a 16th century mosque in the name of Rama just a few months earlier was now reverberating with: ‘Mile Mulayam-Kanshi Ram, Hawa mein ud gaye Jai Shri Ram’ (Mulayam and Kanshi Ram join hands, ‘Jai Shri Ram’ vanishes in the air). The Hindu consolidation that the Sangh Parivar had hoped for in the wake of the Rama temple movement had hit an even bigger obstacle earlier, in 1990, when the then Prime Minister VP Singh implemented the Mandal Commission Report on reservations of Other Backward Classes. Suddenly, the Hindu votes the BJP was counting on were divided into Mandal and Kamandal, as it were.

One man watched these developments with dismay. Just a few months before the Mandal implementation, he had hoped to be remembered by history as a mascot of Hindu unity. Now he looked up in the sky, remembering Rama, praying for a miracle. The miracle would occur many years later, first in the 2014 General Election, and then in much bigger way, in the 2017 UP Assembly polls.

Kameshwar Chaupal, now 61, recounts the exact moment he was called onto the stage in Ayodhya with Sangh Parivar stalwarts and told that he would lay the first brick at the construction site of the proposed Rama temple. “It was such an emotional moment for me that I still get goosebumps when I recall it,” says Chaupal.

Chaupal was born in a remote village in Supaul district in Bihar’s Mithila region. In Hindu tradition, Mithila is home to Sita, Rama’s wife. “When we were growing up, we believed that Rama was our relative,” he says. In songs sung on marriages in his village, the groom and the bride would be referred to as Rama and Sita.

The village is on the banks of the River Kosi, the vagaries of which were a frequent cause of suffering for villagers like Chaupal who lived on its banks. There was no development. It was difficult living there, more so for a Dalit family like his. In the hope that he would make something of his life, Chaupal’s father sent him to a school on the western bank of the Kosi, on the border of Madhubani district. It is here that Chaupal came in contact with the Sangh. One of his teachers happened to be an RSS worker. “But in those days, one would keep it under wraps,” he says. The teacher was a physical education instructor who often incorporated RSS Shakha drills in his regimen. It was here that Chaupal finished his high school. With the help of his teacher, Chaupal then managed to secure admission to college. “The Sangh had a silent network,” he says, “My teacher just sent me to this college with a note for his friends there. He said the rest would be taken care of.”

By the time Chaupal completed his BA, he had become a Sangh full-timer. Afterwards, he was sent to Madhubani region as zila pracharak. It is here that Chaupal first heard of the Meenakshipuram incident far away in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. On February 19th, 1981, about 800 Dalits converted to Islam in Meenakshipuram village in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli district, in protest of the discrimination faced by them at the hands of upper-caste Hindus. “If you really ask me, the seed of reclaiming Ayodhya germinated in that incident,” says Chaupal. In response to the mass conversion, the Sangh formed the Sanskriti Raksha Nidhi Yojana. In 1984, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) held a ‘dharma sansad’ at Vigyan Bhawan in Delhi, attended by hundreds of sadhus and Hindu leaders. One of the key speakers at the conference was Ashok Singhal, the VHP chief who invoked Rama’s name and said that Hinduism was under siege. Another speaker, Karan Singh, the son of Kashmir’s last Maharaja, spoke about the need to rid Hinduism of the evils of caste. Pointing at Ayodhya, Singh said it was a shameful matter for Hindus that they could not even light an oil lamp at Rama’s birthplace. It was at this religious council that a resolution was passed asking for disputed sites at Ayodhya, Mathura and Varanasi to be reclaimed by Hindus. It was also decided that public awareness for a Rama temple should be created through Shri Rama-Janaki rath yatras.

“During the freedom movement, two words from a sanyasi rebellion in Bengal brought the whole nation together. In contemporary politics, Rama will do that. That is our culture” – Kameshwar Chaupal

Share this on

The first of these commenced from Sitamarhi in September 1984, believed to be the birthplace of Sita. Chaupal was a part of this journey. “The response to that yatra surprised me,” he says. “Thousands of people joined us from small villages and towns.”

Less than two years later, on February 1st, 1986, the locks at the disputed site in Ayodhya were opened under Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress regime. In the second phase, plans for the construction of a Rama temple were formalised. Some in the Sangh, says Chaupal, were of the view that a few industrialists sympathetic to the Hindu cause could be asked to donate money for this project, but it was Ashok Singhal who rejected the idea. “Citing the example of Birla temple [built by industrialist Baldeo Das Birla] in Delhi, Ashokji said that every Hindu should feel that he or she has built it and not one businessman,” says Chaupal. So it was decided that every Hindu would contribute a rupee and 25 paise for the construction.

In November 1989 began the shilanyas, a ceremony to consecrate the foundation stone. Chaupal was in a tent in Ayodhya when one of Singhal’s close associates barged in and said that his name was being announced from the stage. When Chaupal rushed there, he saw all prominent leaders looking at him. It was then that he realised the significance of the occasion and his role in what was going on.

What the movement’s leaders wanted him to help achieve had its genesis in the Meenakshipuram incident: the assimilation of Dalits in the Hindu fold. And what bigger symbolism could there be than to have a Dalit lay the first brick at the shilanyas? Chaupal was chosen for this task.

FROM THAT 1989 moment in Ayodhya, Chaupal says, Hindu consolidation began to take shape. By the time the BJP leader LK Advani took out his rath yatra in 1990, the effects of the agenda had become palpable. Chaupal remembers Advani’s chariot reaching Patna, by which time the BJP had got a whiff of the leader’s imminent arrest. “In Gandhi Maidan, the late Pramod Mahajan took the mike and said Advaniji would be arrested,” recalls Chaupal. And that is what happened. In Samastipur, the yatra was stopped and Advani was arrested by Bihar’s Lalu Yadav government of the time.

The consolidation broke in 1990 after VP Singh offered OBCs reservations in government jobs and educational institutions. Suddenly, Hindus were no longer rallying unitedly behind the BJP. Many Dalits began to see “Rama ki ladai” as “oonchi jaat ki ladai”, says Chaupal, Rama’s fight as an upper-caste fight.

But despite these setbacks, Chaupal says, the Sangh Parivar managed to demolish the structure of the Babri mosque in December 1992. He was there when it happened. “I can tell you that no one could have stopped that tide. I don’t know what happened. There were walls that kar sevaks brought down with their bare shoulders. We would shout and say, ‘Run away, the wall will fall on you,’ but nobody listened. They were under some sort of spell,” he says.

Chaupal compares it to a war: “In a battle, only gods are invoked. We don’t say, ‘Gandhiji ki jai, Nehru ki jai’. We say, ‘Jai Bhavani, Har Har Mahadev’.”

On the party’s directive, Chaupal fought the General Election of 1991 against Ram Vilas Paswan, but the upper-caste vote had shifted to the Congress because of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination. In 2002, he became a member of Bihar’s legislative council. In 2014, he unsuccessfully contested an election from Supaul against Ranjeeta Ranjan, the wife of RJD’s Pappu Yadav.

Chaupal feels that the BJP could not do in Bihar what it did in UP because elections in Bihar turned into a backward-versus- forward battle. “In Bihar, there is a lot of work to be done on caste. It won’t be so easy,” he says. But as compared to his childhood days, he says, there is already a sea change within society, though it may not get replicated in politics. In villages now, in marriages and during shraadh ceremonies, there are no boundaries between upper and lower castes, he says. As a child, Chaupal was once fined because he dared to pray at a temple he was not supposed to enter. “I still cannot,” he smiles. “But there are changes. Personally, I feel I have been born thrice.”

Chaupal feels that Rama’s name would remain a major force in India, especially in electoral politics. “During the freedom movement, two words from a sanyasi rebellion in Bengal brought the whole nation together. In contemporary politics, Rama will do that. That is our culture,” he says, “If that culture dies, the country dies.”

/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Karsevak1.jpg)

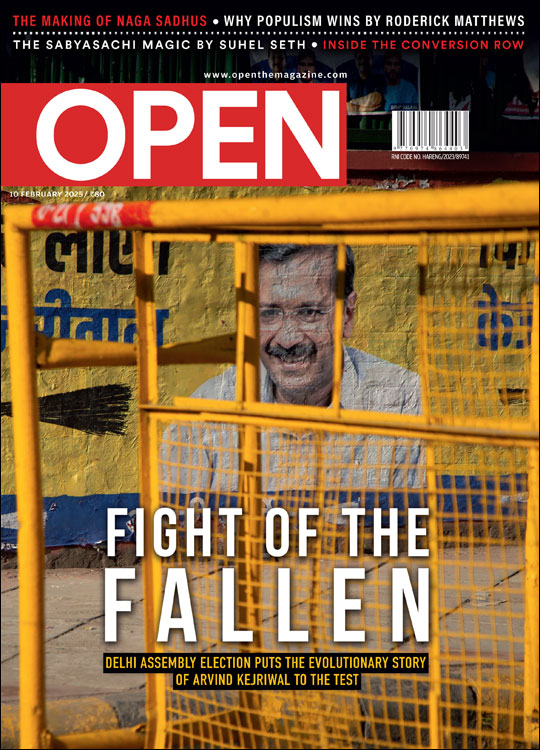

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover-Kejriwal.jpg)

More Columns

Revealed! Actress Debina Bonnerjee’s Secret for Happy, Healthy Joints! Three Sixty Plus

Has the Islamist State’s elusive financier died in a US strike? Rahul Pandita

AMU: Little Biographies Shaan Kashyap