THE PROBLEM WITH BIG BANG THEORY

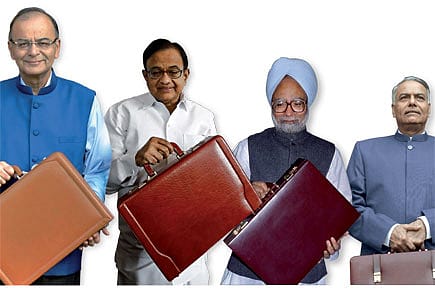

In India, it would seem that every Budget presented must answer to Manmohan Singh's epic 1991 effort. That, and perhaps the one in 1992, is the gold standard for a 'radical', 'reform- ist', 'big bang'—choose your superlative— Budget. It was the beginning of India's decisive move to a market economy from Nehruvian socialism. The silver standard is the Budgets of 1997 and 2000, which also took radical pro-market (and anti-statist) turns. In the former, P Chidambaram stopped the automatic monetisation of the fiscal deficit, slashed direct tax rates, and introduced the Voluntary Disclosure of Income Scheme to clamp down on black money. In the latter, Yashwant Sinha introduced the revolutionary Fiscal Responsibility Bill, promised serious privatisation of PSUs for the first time and announced measures to downsize government.

Most of the commentary after Arun Jaitley's Budget of 28 February, also the 25th after liberalisation, suggests that it failed to meet the lofty standards of 1991, 1997 and 2000. The anguish is only deepened by the fact that Jaitley is the Finance Minister of the country's first majority right-wing Government, which surely must have a mandate for free-market economics like none other did. But the moot question is this: did the Finance Minister or Prime Minister deliberately want to avoid the gold and silver standards of the right- wing commentariat?

The popular political perception is that India has only a limited constituency— in terms of voters—for aggressive market-oriented reform. It is remarkable that there has been a reasonable cross- party consensus in favour of liberalisation and globalisation despite that. Of the three famous Budgets, one each was presented by a Congress, Third Front and NDA Government. None of those Budgets, however, were good enough or perceived to be enough to win the incumbent Government a second term in office. PV Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh were defeated at the ballot box despite altering—upwards—the course and trajectory of the country's economy. The Third Front and its Finance Minister P Chidambaram lasted less than two years, only to be badly defeated in a general election. In both those cases, it is possible to argue that issues other than the economy dominated the elections: Narasimha Rao's Government was plagued by corruption allegations and a split in the Congress, the United Front was unstable, riddled with internal contradictions and reliant on Congress generosity from start to finish.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

Atal Bihari Vajpayee's NDA was the only Government bold enough to go to the ballot box with the slogan of economic reform—twisted into 'India Shining' of course—and with economics top of the mind, it scored an unexpected defeat in 2004. The BJP's top guns—Arun Jaitley was a senior minister in Vajpayee's Government—are still haunted by the ghost of that electoral slogan. The defeat of 2004 saw Jaitley and a generation of the BJP sit out of power for a decade. Having wrested power now again, the BJP will move carefully on how its economic policy is perceived in public. For politicians, policy reform must also translate into good political outcomes. It is frightening to think that the only Government that has won re-election since liberaliation began, the UPA, won in 2009 on the back of a blatantly populist Budget.

Chidambaram's 2008 Budget, which pumped thousands of crore into NREGA and farmer loan waivers, was to become the root cause of India's fiscal mess and runaway inflation. It is India's tragedy that free-market reform is still viewed as pro-rich and populism pro-poor. Indira Gandhi's legacy is still alive, if faded.

Every Budget must also be judged in the context of its circumstances. It makes little sense to compare any Budget to 1991, which was presented in an extraordinary environment. India was on the verge of bankruptcy and the only way out was to force radical reforms. Anyone who had been in the place of Manmohan Singh would have done the same. Sure, credit goes to Prime Minister Narasimha Rao for steering those reforms through Parliament on the strength of a minority government and amid general hostility to the reforms process. Fortunately for Rao and Singh, the polity was distrac- ted by other—quite literally—burning issues. The Mandal and Masjid movements had consumed the leading opposition parties, the Janata Dal and BJP, and opened for the people of India wounds more painful than those imposed by the austerity that accompanied liberalisation. India circa 2015 is very different from India circa 1991.

What about 1997? Certainly, there were no extraordinary external circumstances like in 1991, even though the Asian economic crisis was brewing. Unlike in 1991, there was a strong but vocal constituency for reform. The main priority for the fractious United Front Government was survival. So even though Chidambaram's radical reform proposals upset many of the left-leaning and indeed Left parties in the coalition, he was able to see them through because none of the partners was going to bring the Government down over the Budget. And it was still too early for the Congress to sabotage the regime. The circumstances were fortuitous for reform. The 2000 Budget was less successful in what it managed to get done. Apart from fiscal responsibility, none of the other big-ticket items like privatisation really took off. The NDA's big coalition with divergent economic views was a challenge.

Budget 2015 comes 24 years after 1991 and 15 years after 2000. Plenty of free-market reform has taken place over two-and-a-half decades—not all of it via Budgets but through off-Budget policy measures by successive governments. It's safe to say that most of the low-hanging fruit has been plucked. There are no obviously irrational licences to abolish, no ridiculously high tax rates to be cut, no absurd import duties to be reduced. What remains are the tough, politically contentious moves: such as labour reform, land acquisition, a further lowering of tax rates for the 'rich' (only the relatively rich pay taxes), subsidies (fertiliser and food), wholesome privatisation (and not stealthy 'disinvestment'), aggressive liberalisation of banking and finance, and the Goods and Services Tax. In short, what constitutes radical reform in 2015 is much more radical and contentious than what constituted radical and contentious reform in 1991, 1997 or 2000.

Arun Jaitley's first full-year Budget doesn't make a dent on even half those important reforms. It was never realistic to expect big bang moves that would encompass all that remains to be done to fix India's economy. To be fair, many of those reforms are not meant to be packed into a budget. And beyond the Budget, the ruling party's lack of a majority in the Rajya Sabha means that getting radical reform through is tough—as the examples of only mildly reformist legislation on land, mines and insurance have shown. The Government has to watch its numbers before going gung-ho with reform.

Despite all of that, Jaitley did manage to pack enough in to suggest that this was a budget of high standard, one for the times. The top priority now is to revive India's growth rate towards double digits. That is the best way to bring prosperity to the middle-class and lift hundreds of millions out of poverty—defining outcomes of the period of high growth between 2003 and 2007, which won the UPA a second term in office. And the only sustainable way to revive growth is through investment, public and private. Sensibly, Jaitley relaxed the Centre's fiscal deficit targets to boost public investment. Boldly, he proposed a lowering of the corporate tax rate from 30 to 25 per cent. To make it politically feasible, he spread this out over four years and said that he would remove all exemptions which take the effective corporate tax rate closer to 23 than 30 per cent. He broke from received wisdom to enact both these measures. There are other measures in the Budget to boost investment and manufacturing: a correction in the structure of duties which harm manufacturing; reform of the RBI, which will bring greater clarity and purpose to the fight against inflation and new funds which will finance small enterprises and microfinance institutions.

Perhaps the one area in which there were expectations of radical reform was subsidies. To be fair, the Government has already decontrolled fuel prices. In any case, low global oil prices have eased some pressure on the subsidy bill. Fuel subsidies were the most misdirected of the three major subsidies. Food and fertiliser also need rationalisation, but both Modi and Jaitley would be wary of blanket cuts. The opposition would immediately corner them—farmers and the poor are big vote banks. Instead, it is likely that the Government will wait to roll out the Direct Benefits Transfer system pan India and then move to target food and fertiliser subsidies via cash transfers at the needy. It is only then that the subsidy bill will be cut by removing benefits from those who do not qualify to receive subsidy support. The sequencing is critical. It can make all the difference between a popular reform and a politically disastrous one.

The other big miss in Jaitley's Budget would be privatisation. Again, the Govern- ment would be sensitive to perceptions. It is easy for a small minority of vested interests to derail a big-bang privatisation effort by creating a lot of negative publicity that will be lapped up by the media and sent through drawing rooms across India. For Modi and Jaitley, it probably makes better sense to begin with the low- hanging fruit and then move on to tougher nuts. It is not a Budget exercise. Every ministry that has PSUs under it should draw up a plan where it decides which ones are up for disinvestment, privatisation, or retention in government control. The Government can consider these on a case by case basis.

In politics, perception is as important as reality. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is conscious that his Government must not be portrayed as pro-business and anti-poor. In the minds of Modi and Jaitley, the danger with a big bang is precisely that. Ghosts may not exist but they have the potential to create fear in the minds of the superstitious. Whether the 'rational' commentariat likes it or not, the reality is that NDA-II is still haunted by 'India Shining'. Expect only cautious, creative incrementalism from this Government.