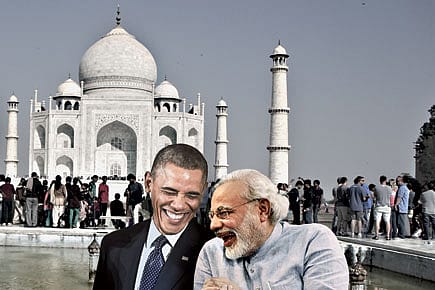

THE ODD COUPLE

As Indians prepare to receive Barack Obama as chief guest at their Republic Day celebrations, they would do well to bear in mind that the American president mentioned India in his State of the Union address precisely zero times, fewer times than the word 'transgender' (whose maiden appearance in a State of the Union speech sent a frisson through America).

In an address that lasted for an hour, delivered just five days before his departure for New Delhi, Obama made no mention of the hysterically hospitable country which will welcome him for the second time in his presidency, shutting down city roads, Metro stations, highways and historical monuments in an effort to make the most powerful man in the world terrorist- proof. No sitting American president has made a state visit to India more than once, and no American president has been honoured with the opportunity to review two hours of parading soldiers, camels, missiles and provincial tableaus. Poor man. Mustachioed jawans, marching in lockstep, have their martial charms; but no one should have to endure those infernal floats, so redolent of an older, dowdier India.

Obama comes to India as a lame-duck president, and he comes at the invitation of an Indian prime minister who is on a diplomatic tear. A man who many had feared would be a narrow nationalist, hemmed in by his Hindutva and his undeniable Gujarati parochialism, has turned out to be a rampant internationalist. In the eight months since he became Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has been on major outings to Japan, Australia and the United States, all of which he took by storm, offering a vision of an assertive India that sought business, friendship and security partnerships. He has played host, in India, to both Xi Jinping of China and Vladimir Putin of Russia—not to mention Nguyen Tan Dung of Vietnam, to whom he offered Indian naval vessels and increased investment in Hanoi's energy sector, much of it centered in maritime zones claimed by Beijing. And now, he plays host to Obama. The American president was last in India in 2010: then, he was the one full of vigour and ideals, while his host, Manmohan Singh, was the lame duck. How times change.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Why is Obama coming to India? The answer is, at one level, straightforward: Modi, in a rush of blood, invited him in November last year to be chief guest at India's 66th Republic Day. It was an overture Obama could not spurn without appearing churlish. No American president before him had received such an invitation. Chief guests at India's Republic Day have been, more often than not, innocuous statesmen from middle-ranking countries. Although French presidents are frequent guests, the heads of government of other Western powers are seldom invited, their presence being seen as inimical, in some way, to India's non-alignment. Certainly, the presence of an American president has been a long-established taboo, made doubly so by New Delhi's intimacy with Moscow. In inviting Obama to an occasion of such symbolic national import, Modi struck a welcome blow against the anti-Americanism that still prevails in the corridors of Indian officialdom.

On his visit to the United States in October, Modi established a rapport with Obama that was as healthy as it was improbable. Many commentators in India and the US had foreseen a rocky relationship: How, they asked, could the avowedly liberal, adamantly secular Obama possibly hit it off with Modi, who, until the very eve of his election, still bore the stigma of having been refused a US visa for his alleged role in the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002. But the two men, by all accounts, got along like a house on fire (if you will permit the indelicate metaphor). Obama, in the autumn of his presidency, was perhaps too weary to lock horns with Modi. Besides, why should he have done so? Here was a man—Modi—who had been elected by a resounding majority in the world's largest democracy, and had shown himself to be big enough to forgive (if not forget) American diplomatic slights. He received a welcome bordering on adulation from Indian- Americans, many of whom are (for the moment at least) Democrats. And he came not only with his hand extended to Obama, but with an attitude of avid Amerophilia quite unprecedented in an Indian prime minister.

The relationship between India and the United States is a particularly frustrating one— to both Indians and Americans. It oscillates between certifiable tedium and blousy expectation. The tedium resides in the unchanging nature of the mutual dynamic: both sides recognise that they share values, these being democracy, pluralism, secularism (yes, India is still a secular place), the rule of law, and a belief in an international order in which disputes between nations are resolved without an impulsive resort to force. There are also powerful shared interests: both countries have been the victims of Islamist terrorism, and are committed to defeating the menace. And both regard China with increasing apprehension, believing—rightly— that an amoral, hypernationalist, mercantilist Beijing is hellbent on taking for itself everything that it can, be it territory, resources, trade surpluses and jobs. This last is the fear that dare not speak its name. America is loath to speak openly of 'containing' China; and India— woefully mismatched in military and economic terms when it comes to its northern neighbour—is anxious not to embark on a partnership of 'containment' for fear of provoking Beijing, which, under Xi, is more consistently bellicose than it has been at any time since the death of Mao.

The tedium in the US-India relationship resides in the constant invocation of these shared values, without either country ever taking matters to the next level—that of a formal alliance. Comforting assertions abound, which, in turn, give rise to periodically heightened expectations, all of which are rendered sterile by an ineradicable inertia. The 'landmark' nuclear deal signed by the two countries during the Bush administration has hit an impasse over India's nuclear liability laws. The deal allowed American companies, for the first time, to build nuclear reactors in India; but India's insistence that suppliers, rather than operators, be held liable for damages in the event of an accident at a nuclear plant has meant that not a single plant has been built. Given the advantages of such plants to energy-starved India, one would have thought that a creative solution would have been found to amend—or circumvent—the liability laws. But none has been forthcoming. Instead, a pseudo-populist paternalism on the part of the Indian state (harking back, in many ways, to the Bhopal accident in 1984) has left the two countries with a still-born deal.

Obama's visit to India will not resolve this issue. Nor will it resolve American differences with India over climate change, clean energy, trade and economic barriers. There will, no doubt, be some 'progress' in these matters—there always is—but he will return to Washington having mouthed the same platitudes that he mouthed when Modi was in the American capital. Modi, too, will offer buzzwords and slogans about Two Great Nations, and everything will be comforting and frustrating in equal measure.

The truth is that there is nothing that the two countries can easily 'do' for each other. India cannot give the U.S. greater ballast in Afghanistan. The US cannot exert any more pressure on Pakistan to cease its sponsorship of terror than it already does. India will not commit to help contain China, even as it does take on an increased role in maritime patrols on the high seas. Washington cannot make American nuclear companies set up shop in India, nor compel its manufacturers to 'Make in India': they will only do so if the market conditions (including questions of legal liability in the event of nuclear accidents) are propitious. The US cannot make India cut its carbon emissions; not until India is ready and willing to do so. The fact that the Chinese have agreed to cutbacks will matter not one jot to New Delhi, which believes that the Indian and Chinese economies are at vastly different stages of development.

The United States cannot, also, make India take a harder line on Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine, nor against Iran for its nuclear shenanigans. As Robert D Blackwill, a former US ambassador to India remarked recently at the Aspen Strategy Group dialogue in New Delhi, India "believes it has no tiger in the Ukraine fight; has important military equities with Russia to protect: and moreover wonders why Washington is driving Putin further into Xi Jinping's embrace."

Blackwill, a man of robust realism with a fine understanding of India, addressed the question of US strategy toward India in his Aspen Group paper. His conclusion was subdued, even pessimistic. 'In my judgment,' he said, 'at best our expectations should be modest. Unlike at the beginning of the last decade, neither this Prime Minister nor this President will put the strategic transformation of US-India relations in a preeminent place in their overall policy agendas. There will therefore in my judgment be no real strategic partnership between the two countries in the next two years.' As simple, and as blunt, as that.

The former ambassador added, for good measure, that "Indians do not react well to hectoring from insistent folks from across the ocean; that tends to remind them of their former colonial masters. In any case, if India moves ahead with its domestic economic reforms and thus encourages US business to further enter the Indian market, and the United States has some patience and does not attempt to pressure the Modi Government to damage any of its other major bilateral relationships, we can together make incremental progress on some of the bilateral issues, which is not to be dismissed. But that is at best, and there is always whatever intrudes from elsewhere in the world."

Blackwill was a Bush appointee and, as such, is perhaps inclined to write off Obama. His predecessor in New Delhi, Dick Celeste—a Bill Clinton man—is more upbeat. In an email to me on the eve of the Obama visit, he said: 'Barack Obama will be the first American President to visit India twice during his presidency. As he approaches the end of his eight years in office, India offers one of the rare opportunities to achieve sustainable progress when at home and across the globe he faces difficult and unrelenting challenges.' So for Obama, 'taking significant steps to promote closer economic and strategic ties with India would represent a capstone achievement. For Prime Minister Modi, early in his tenure, such steps on the economic and strategic fronts would represent cornerstone achievements. This is a rare moment when the ambitions of both leaders are in close alignment.'

The best way to assess the significance of Obama's visit is to look past the granular detail. Relations between India and the US have never been better, and never warmer, than now. In Modi—or at least in the best reading of his intentions— India has an economic reformer who would like the world to invest in India. His vision of India is that of a strong, prosperous nation that can hold its own, unapologetically, at the High Table of nations. American policymakers are aware that a strong India can only be a force for stability in the world, and that such an India—for all its prickliness and vestigial non-alignment—would be most comfortable in a world where the United States, with its democratic values, its reserves of capital, its economic and scientific leadership, and its increasingly influential Indian diaspora, offers the best insulation against a hostile China.

For the first time in their respective histories, the US and India today approach each other as something resembling equals, and with a mutual respect and lack of suspicion that was distressingly absent in the past. Washington no longer patronises New Delhi. India is no longer impenetrable and insufferable, but increasingly flexible and pragmatic.

Where once its foreign policy was a strictly local affair—Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, with a dash of Burma thrown in—India today is both more global and more worldly. Obama, a keen student of history, knows this, and has responded. His successor, whether it be Hillary Clinton or—most improbably—a Republican of as yet unknown identity, will surely be inclined to consolidate the relationship. And with time, the consociation may grow into real partnership, not of the kind that Washington has with Britain, or Israel, or Japan, but, perhaps, like the one it has with France, another proud, complex and complexed nation, which is loath to submit itself to the American 'hegemon'. New Delhi has always admired the way the French manage their alliance with, and distance from, the United States. If India can find a way to do the same, the US could get itself a partner for the ages.