In Praise of the Risk Taker

What does the rise of Modi and Kejriwal, and the stalling of Rahul, say about Indian politics?

I did not start out as a political reporter. I only strayed into that most vaunted—and fun—part of our profession. Once in a while when the senior political dadas were not available for some reason. Or when, as a cub reporter usually left to cover crime in a city so benign it averaged only six murders a year (Chandigarh) or dealing with what was called, in typically vicious newsroom language, tray-and- fire (the clip-tray with press releases like some 'Lions Club' celebrating Diwali with 'pump and show', and the routine call to the fire department before going home), you were told to go to the usually empty state assemblies late afternoon when real business was over and members' private motions were discussed. My own debut in political reporting was the equivalent of the golden duck. I returned breathless from my first afternoon in the Punjab assembly, not even twenty- one yet, and started explaining all the fascinating private members' bills that were discussed. 'You just be a good Pandu (old Mumbai-speak for a cop) and focus on accidents and robberies,' said Balan, our much loved chief sub-editor. 'Leave politics to senior people, and please take all private motions to your home. This is my newsroom.'

But there were still learnings, and early learnings are the most useful. One of the first was never ignore politicians when they are out of power. That is when they have the most time and patience for you. They are also likely to remember this with some warmth, if not gratitude, when they return to power, as they almost always do. I sat sometimes to get some political gyan from, who else, but Giani Zail Singh when, as leader of a decimated Congress after 1977, he sat on dharna in Chandigarh's Sector 22, with a motley group of protesters that nobody paid any attention to. He taught me patiently about caste and class in Punjab, of how it was nearly impossible for a non-Jat Sikh like him (he was a Ramgarhia, traditional carpenter) to become chief minister in that state and how remarkable it was for Indira Gandhi to have elevated him to that. Zail Singh lost power in 1977. Since then Punjab has had seven chief ministers. All of them have been Jat Sikhs. And it seems unlikely to change soon. Years later, when Indira Gandhi made him the first Sikh president of India, he never forgot the 'khapachhi' (scrawny) reporter on a red motorbike and found time for me even though Rashtrapati Bhavan was way beyond my station yet. And you always learnt politics from him. At the peak of the Punjab terror, when my friend and mentor Arun Shourie was really angry with the bungling Indira government, I sought time for him and myself with Gianiji. He hosted us for tea on the lawns of Rashtrapati Bhavan and tried calming Arun by playing down, even trivialising, the threat.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

'Munde ne tey goondey ne' (There are urchins and goondas), he said. 'What else is the problem? All you need to deal with them is intelligence.'

'Intelligence? What do you mean, Gianiji?' Arun asked. Zail Singh told us a rather colourfully involved story of how, when he was chief minister of Punjab, he had made sure his DIG (CID) reported to him directly and not to his home minister, unlike the rest of the police. At the same time, he had a mole of his own in the Akali Dal working committee. His DIG (CID) was forever irritated that his chief minister seemed to get the inside dope even before him. One day, Zail Singh said, the DIG stormed into his room, excited. 'I have discovered your source, sir,' he said. It was a woman member of the senior Akali organisation. Gianiji smiled in acknowledgement.

'But sir, she is a woman of poor character. What kind of woman are you in touch with, Chief Minister Saab?' the DIG asked.

'Oye DIG Saab,' Gianji said. 'Aisa kaam bure character ki auratein hi karengi na, achche character ki nahin. Yeh intelligence ka kaam hai' (You think women of good character will be your moles? You need a woman of poor character here. This is the intelligence business), he told the sheepish DIG. This is perhaps why he wasn't such a successful spook.

But on that late sunny winter afternoon on his west-facing lawns, both Arun and I had learnt a brilliant lesson in politics and governance. And this, from a man with almost no formal education. And such uncluttered views as expressed in his speech at the World Congress on Anthropology which he inaugurated at the Panjab University campus as chief minister and where I helped as a journalism student volunteer. 'I do not understand you scientists,' he said. 'If man descended from monkey, tey tota kithhon aaya?' (Then where did the parrot come from?)

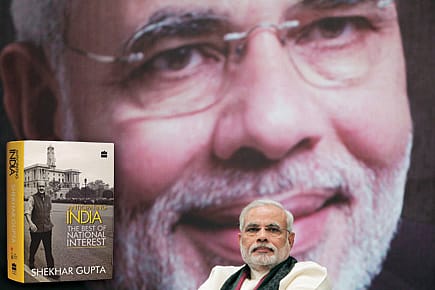

A theme you would find recurring often is how politics is frozen in our country, failing to keep pace with the voter and something's gotta give at some point soon. Precisely that has happened now and the three Indians who personify the shift that is generational as well as political and philosophical are Narendra Modi, Arvind Kejriwal and Rahul Gandhi. I have argued with all three. Not just argued, but even fought, as many of Modi's supporters, masked or not, say. Reporters of the Indian Express have also broken several of the 2002 riot stories that Modi has still not been able to put out of his way. Yet, Modi and I never broke civilised conversation. Which is much more a credit to him than to me. Because I am, after all, a shameless, old-style reporter type. I never stop talking to anybody my writings may have torn into, or not answer phone calls from anybody whosoever. Generally, Indian politicians have that quality as well. God knows I had done enough to make Arjun Singh furious over the years. He even called me early one morning with a dire warning that if the man in whose name we ran the Indian Express (its redoubtable founder Ramnath Goenka) had been alive, I wouldn't have lasted one more day in my job. But he always returned my call, found time whenever I asked, and then engaged.

I know the great secular manipulator's followers would chafe. But Narendra Modi, even at the other end of the ideological spectrum, is equally an old-fashioned politician, always with a ready smile and hug. He called me just once to complain about a story that Muslims were being denied NREGA benefits in Gujarat (and it turns out that he was right on that one). He said, 'You abuse me all the time for Hindutva, which is your right. I also can't complain because I do believe in Hindutva. But you cannot call me so cheap [ghatiya] as to deny a hundred rupees a day to my Muslims.' Later as we got to talk more often, he said I was the one critic he fully engaged with because while I cursed him for what I disapproved about him, I was also willing to give him credit when he did something right, as with his economy and infrastructure, particularly power. It was in a Walk the Talk with me in 2004 that Modi came closest to expressing remorse for 2002.

Modi, therefore, also has that one essential asset in Indian politics: the armour of a thick skin.

I am not sure you can say that about the two others in this upcoming race between the three. Both Rahul Gandhi and Kejriwal are still wary of those who disagree with them, though in their own different ways. Unlike Rahul, Kejriwal is an enthusiastic communicator in public, whether campaigning door to door or on the big stage. I have argued with him and the Anna movement often and several of those writings are included in this collection. He asked me, in a conversation, if I had checked with my marketing people how the line the paper had taken on the Anna movement was working with our audiences. I said I wasn't producing an entertainment channel or a Bollywood film and audience preferences should never be the main determinant of news value. On reflection later, however, I had to concede that Kejriwal had figured out the modern news media's greatest weakness: eyeballs. And his success in exploiting that (entirely legitimately) has contributed greatly to his brilliant success. As he grows in stature as an elected member of the establishment now, and fights on a much higher stage, it is a matter of time before he also imbibes that essential lesson of our politics: that you must continue to engage with all, particularly those who argue with you.

The rise of Modi and Kejriwal, and the stalling of Rahul, has also underlined for us again the value of decisiveness and risk- taking in Indian politics. By fighting to become a candidate for prime minister, Modi has risked even losing his safe perch in Gujarat. Kejriwal has been an even bigger risk-taker, challenging Sheila Dikshit in her once impregnable fortress and not even covering himself by fighting in a safer constituency as well. We Indians love giant-killers. And while I have sometimes compared Kejriwal's defeat of Sheila with Raj Narain beating Indira Gandhi at Rae Bareli in 1977, the comparison is inapt, because Kejriwal is no comedian or maverick like Raj Narain. He is a challenger of substance in the long run, one you would describe as a lambi race ka ghoda.

All three will change and evolve in months to come. Modi towards moderation, Kejriwal towards a little establishmentarian calm, and Rahul may shed some public diffidence and risk avoidance. Together, the trio will lead a brilliant cast of political characters who never leave you short of an idea when you sit down to writing another National Interest on a weary Friday afternoon.