The Awakening

Earlier this month, I was on a brief visit to London, a visit that coincided with the 60th birthday celebrations of a close friend from a past life. My friend, a well-known figure in the British media, was an unreconstructed Leftie whose idea of commemoration consisted of showcasing a bust of Karl Marx, tastefully sculpted in ice. The lovely, quintessentially overgrown English garden was dotted with grotesque caricatures of Boris Johnson, once a fellow journalist and now destined for an innings as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. There was even a Boris piñata — inspired by a Mexican Catholic custom of flaying temptation — that, as the evening got merrier, was pulverised with sticks and would probably have been burnt like Guy Fawkes had the stringent European Union regulations not made it a health and safety hazard.

In his brief but spirited speech, the birthday boy railed against fascists, Brexiteers and Etonians and was lustily cheered on by the crowd of ageing Leftists, most of whom had made a modest success of their lives.

Returning from the party later in the evening, I reflected on the fact that the more things change, the more they remain the same. Maybe not exactly. The ice sculpture of Marx would be the constant, but in an earlier age the pet hates would have been nominally different: there would undoubtedly have been a Thatcher piñata and maybe, just maybe, the celebrations would have included a full-throated rendition of the Internationale, with a recording of the Red Army orchestra as background noise.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A deeper reflection would reveal that the terms of Left innocence have changed fundamentally. In an earlier age, the Left meant a commitment to the class war. It meant denouncing privilege, it meant fulminating against inequalities, deifying the working class and even shedding copious tears for the underprivileged in the Third World. The Right was always the Establishment and, by implication, worthy of being dubbed fascist. It also meant intellectual vacuousness of the type Monty Python lampooned as upper-class twits.

Few of those assumptions would have held true for the Marx that stood slowly melting in the summer heat. The terms of engagement have changed dramatically. The class wars still linger in obscure corners, but the real battles being fought three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall centre on national identity. This is most apparent in Europe but equally visible in North America where things tend to get overshadowed by the powerful presence of a president who doesn't seem to care what he tweets and what diplomatic niceties he recklessly violates.

Nationalism and national identity were thought to have died shortly after World War II and replaced by cosmopolitan chants of 'London, Paris, Rome, Berlin/ We shall fight and we shall win.' Now nationalism and faith in the nation-state are on the ascendant. The British impatience with the slow pace of the Brexit negotiations is well known. It has created convulsions within the Conservative Party, engineered the resignation of a middle-of-the-road Prime Minister and seems likely to send Boris Johnson into 10 Downing Street. At the same time, it has fostered the formation of a Brexit Party led by the jolly Nigel Farage — he should have been the real hate figure of the Lefty party I attended — that topped the elections to the European Parliament. However, along the Brexit warriors there has been the grandstanding of Viktor Orbán who has invoked Magyar pride to pit Hungary against the European Union. And then there are the amateur politicians who have indicated that Italy will not accept being North Africa's human disposal receptacle. The bright lights of multiculturalism and cosmopolitan existence are slowly going out all over the European Union and we may never see them again in our lifetime.

What worries the Left is not merely its own organisational and political irrelevance in the midst of such profound churning but that the working classes — the supposed vanguard of the revolution that never was — are providing the electoral ammunition of this populist identity surge. Whether in Italy or France, countries that boasted formidable Left-wing parties after World War II, it is the erstwhile Communist strongholds that have shifted allegiance to the New Right. In the 1960s, the opposition to immigration in places such as Britain and France came from those who were embittered by the loss of empire. Today, the desire to preserve a country's national character, both in cultural and ethnic terms, are coming from those who claim impeccable working-class pedigree. In the UK, the Labour Party has found itself in a twilight zone in the Brexit debate because its cosmopolitan activists — whose political lineage can be traced to the 1968 upsurge and the ensuing radicalism — are out of tune with the older traditions of the party.

In a curious sort of way, the trends in Europe are being replayed in the United States. The election of Donald Trump sent shock waves in both the liberal East Coast Establishment and the campus radicals who, together, had contributed immeasurably to the deification of a new liberal order under Barack Obama. For the first half of the Trump presidency, they took solace in laughing at the unusual president and gloating over his apparent stupidity. However, simultaneously it became clear that the opposition to Trump was being crafted almost entirely on the support of Black and Hispanic voters and young White voters with a penchant for a particular lifestyle. Those who considered themselves left out of the larger social and economic changes gripping the US and were, at the same time, most comfortable in the insular 'American way' thought Trump was the answer to liberal over-indulgence. In a bizarre way, the strident anti-Trump sentiments have driven the Democratic Party into the arms of a Left that dotes on high taxes and liberal immigration. Where this is leading the US to is unknown. All that can be said is that America's hegemonic status in the world is being whittled down by internal developments.

How do events in the First World play out in India?

I am sure there are private enclaves — and not merely in the rarefied surroundings of Jawaharlal Nehru University — where private celebrations are combined with political assertions of Modi and Amit Shah's evilness. Ever since this outlander duo barged into national politics, Left and liberal India have had a ball declaiming against the banal stupidity of the so-called bhakts. It was assumed that having won by an inexplicable fluke in 2014, Modi would implode in the next few years not least owing to a subaltern upsurge, led naturally by an enlightened few with a renaissance idea of India. Despite alternative indications, they clung to a caricatured view of the Modi Government being bereft of support from all sections except venal crony capitalists, upper-caste social conservatives and ideological Hindutva die-hards.

This perception was rudely shattered on May 23rd when the Electronic Voting Machines revealed that Modi had not merely retained his 2014 support but had added significantly to it. More to the point, there was ample electoral evidence to suggest that it wasn't merely Middle India that had reaffirmed its faith in Modi but large chunks of the non-Hindi-speaking belt in eastern India. In West Bengal, hitherto the bastion of aggressive secular politics, voters were seen taunting the chief minister with chants of 'Jai Shri Ram' — a situation that left Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, the epitome of high cosmopolitanism, totally horrified and devastated. In large parts of Assam and Northeast India, Modi was favoured as an avatar of economic development.

IT IS UNFAIR to mock the vanquished for their disorientation. When India embraced a market- friendly approach to economic policy and followed it up by cautiously opening up the country to the forces of globalisation, there was an unstated belief that this would mark the end of the old Hindu Right and its replacement by a more Progressive Right modelled along the lines of the European centre-right. It was believed that with globalisation, rigid perceptions of national identity were unsustainable and that the philosophy of nationhood would become more Nehruvian, minus the attachment to the big state. In particular, it was believed that sustained cultural contact with the world would drive India into the arms of the goddess of liberal values, as long as the inequalities of globalisation were kept under check.

In the West, a similar project got unstuck by the vagaries of globalisation. Historically, free trade had been the signature tune of countries such as the US and Britain. Whether it was the British Empire or the Monroe Doctrine, a combination of political power and industrial might sustained the economies of the West. However, towards the last years of the 20th century, particularly after China came into its own, globalisation began to produce domestic casualties. It led to the decline and, ultimately, closure of the big centres of manufacturing. True, the evolution of a new Knowledge Economy prevented total economic collapse but there was no denying the human costs of the transition from the old to the new. It is interesting, for example, that Trump finds his greatest support in the rust belt and the centres of agriculture production. His fiercest opposition comes from the east and west coasts — the centres of finance and new technology: the beneficiaries of globalisation.

India has been one of the principal beneficiaries of globalisation — although the process is not uniform. Logically, if the belief that economics moulds politics holds good, the political centre of gravity should have moved in a markedly liberal direction. It clearly hasn't. I think one of the main reasons why this process was stalled was the unanticipated growth of Islamist radicalism.

Till the revolution in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979-80, pan-Islamism was the prerogative of West Asian states flushed with petro-dollars. However, as the conflicts in that region intensified and assumed different complexions, the fallout in the subcontinent became more profound. Pakistan was undeniably the worst affected as it drifted away from the Ataturk-Pahlavi model towards internal strife and Islamism. In India, there was a marked increase in terrorism, with the Ayodhya movement also being a significant internal trigger. However, much more than the actual blasts, terrorism led to the deepening of a pre-existing communal schism. Hindus in particular felt increasingly beleaguered and were confronted with a realisation that they had no political weaponry to preserve their heritage from both liberal and Islamist encroachments. While liberals celebrated the coming of age of fragmented politics — caste assertions, gender consciousness and exaggerated libertarian impulses — the Islamists went the other extreme, promoting social seclusion of Muslims, flexing demographic muscle and encouraging the secession of Kashmir from India.

That there would be a sharp reaction was inevitable. Had uber liberalism been the dominant trend, there would have been a corresponding rise in social conservatism and even a possible disavowal of the trappings of modernity. As a political construct, Gandhism was there, ready and waiting for all those anxious to equate modernity with alien mores. The reaction, however, centred more on anxieties over terrorism and the possible disintegration of the nation-state. Indian nationalism didn't begin fading out after the country secured Independence in 1947. It was sustained through the past decades by a combination of wars with neighbours, real and perceived slights, victories on the cricket field and, above all, by religio-civilisational solidarity. It is erroneous to suggest that this was the sole contribution of Narendra Modi. The present Prime Minister may have helped blend nationalism with a fierce sense of individual and collective betterment, but the mood in today's India was built layer by layer by diverse individuals ranging from Indira Gandhi, APJ Abdul Kalam, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and even cricketers and Bollywood stars.

Today's India has often been compared by precocious, radical writers to Erdog˘an'sTurkey and Putin's Russia. There may well be similarities in the leadership's formal and informal repudiation of liberalism. However, at the end of the day what marks the three is a sharp detachment of the common people from those who believe being Indian is an accident of birth. What Indians have successfully done over the past few decades is to leave their own mark on everything: from masala dosa in the canteens of Silicon Valley and Bollywood to the domination of cricket to the evolution of Indian English.

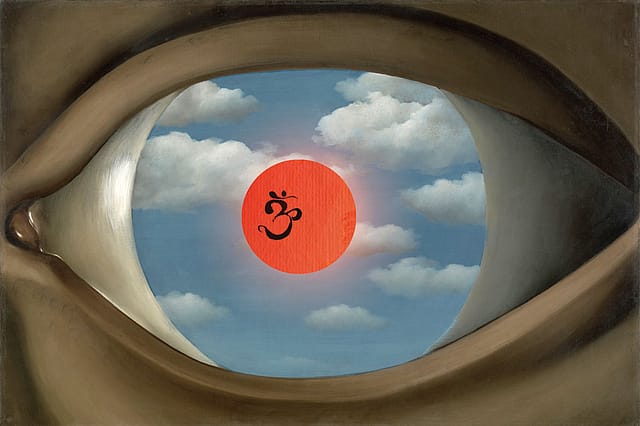

The Indian — you may well call it Hindu — assertion that is so visible today is based on supreme overconfidence. Maybe there is also anger, but that is more akin to impatience. Not like the political bitterness of the ageing Lefties I still encounter in the global centres of cosmopolitanism.

India feels it is winning; the West is convinced that its decline is irreversible. It may all be false consciousness but for the moment it is real.