The Bloodlust

IN 2014, JENNY BHATT moved back to India from the US after more than two decades of corporate work. She was ready to reinvent herself as a writer.

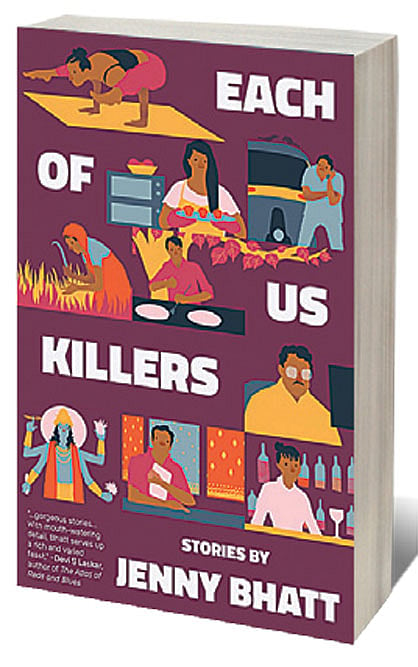

In Each of Us Killers, Bhatt’s debut collection of short stories, characters stand at the precipice of similar life-altering moments. Driven by power, lust, love, recognition or simply a desire to make their lives bearable, people arrive at epiphanies that change the course of their lives.

One comes to a collection titled Each of Us Killers expecting to find violence, and one does. The violence, though, is not always physical. It predicates on everyday attacks on the mind and soul in our deeply inequitable and capitalist society. Built on a variety of literary techniques of plot, style and voice—including the refreshing second-person singular and first-person plural—Bhatt’s stories effortlessly straddle class, caste, gender and race divides spanning the US, England and India. Bhatt herself has lived in these countries and brings her familiarity in the form of journalistic attention to detail.

The opening story ‘Return to India’ is based on the murder of Indian techie Srinivas Kuchibhotla in Kansas in 2017. Like Kuchibhotla, Dhanesh Patel or Dan is the victim of a hate crime in Texas. Using persuasive conversational style, Bhatt pieces together his portrait from the point of view of his white American colleagues. In these testimonies, one recognises the casual racism faced by Indian immigrants in the US in their daily lives. ‘I invited them to my church for New Year’s Day service, you know, but I guess they had their own religion,’ says one of Dan’s colleagues. ‘Probably wasn’t easy for Dan to start taking orders from a woman, given

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

the part of the world he’s from,’ says another.

If Dan is confused for a Middle Eastern man, in ‘Disappointment’, an Indian woman bartender in the Midwest is called a ‘Black bitch’: ‘How can you take someone seriously if they cannot even get your ethnicity right?’

Bhatt’s stories, even those that are constructed as dream-like sequences, are part of a larger sociopolitical framework, whether in India or abroad.

Individuals navigate the liberating and stifling spaces of work and employment against forces that are often beyond their control.

‘Neeru’s New World’ is about a maid whose employer is not much older than her ‘but her status as the mistress of the house made the distance between them such that anything Bhabhi said to her sounded like an elder talking to a child or a dimwit’. In ‘Mango Season’, a saree-seller who has been ‘invisible to the world’ makes the mistake of fantasising about a ‘certain class of customer’ whose grateful and loving look had ‘sent a sudden, ridiculous frisson of anger’ through him.

In the world of Bhatt’s stories, women come of their own, often after experiencing the cruel blows of a misogynistic society. In two separate stories, a yoga teacher and a baker, both living somewhat on the margins, arrive at realisations after passionate sex with men who pay them attention. In ‘Journey to a Stepwell’, a moving folktale narrated by a woman gives her daughter the push to call off her engagement with a man who fills her body with pleasure.

Bhatt’s series floats from memories to moods, thoughts to utterances, confidences to betrayals. She alternates seamlessly between the prosaic and poetic, employing by turns, a feather-light touch of humour and a profound, pensive wisdom. Bhatt’s deft use of language can be summarised by her own words about a character: ‘With the power of her language, she will be able to say anything. Yet, most superbly, she will be able to say nothing.’

Bhatt examines the human condition complete with regrets and ‘the exquisite hopes of youth and how, in time, life eats into them’. There is promise and there is loss. Ultimately, the book is about being ‘unable to speak of [the] corrosion burning away within each of us killers’.