The Name of the Change

Change is a word that has lost its lustre due to the overuse of it by both politics and journalism. It is a word killed by premature aphorisms and desperate slogans. Still, there are times when this worn out word regains its original resonance. When dead certainties crack open to reveal the raw passions of freedom. When ideas of tomorrow redeem power from its darkest corridors. When a people seek the authenticity of hope amidst faux alarmism and dubious sociologies. And when dreams defeat fear.

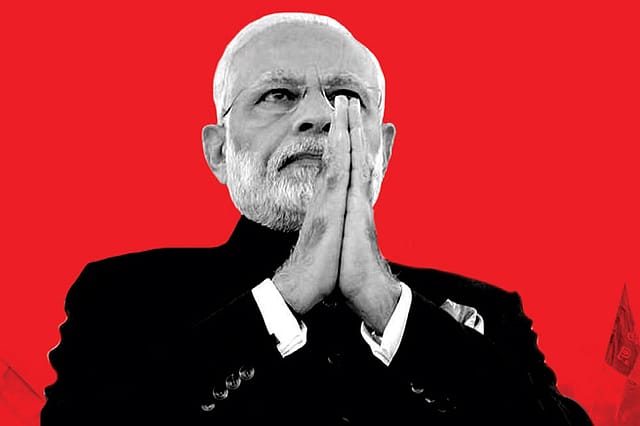

India is at that moment in its evolutionary story as a nation state, when the biography of change is written by one man alone, Narendra Modi. Five years ago, when Delhi fell to the force of the One, we wrote in this space that "Narendra Damodardas Modi, the winner of India 2014, is the story of our time, a story in which the power of one man's will merges with the possibilities of a nation still dreaming." The story has not lost its narrative frisson. Today, as India stands in thrall to the magnitude of a historic mandate, he is the only story that matters, and the sweep of which makes the redundancy of other salvation fables that transfixed India in another time starker. This is a story that can be told only in the hyperbole of change, still.

It is the personal that adds intimacy to the politics of change—and makes it an emotional covenant with the people. In the story of Modi, the personal overwhelms the political: It's the biography, stupid! Five years ago, when he stormed Delhi, it marked a cultural rupture in Indian politics, the backstory of which was dominated by inflated legends of the family, and whenever the monotony of the dynasty was interrupted, well, it was the vaudeville of the federal alternative that we suffered. Modi broke the idyll of a system sustained by entitlement and greed.

He brought in a sense of Indian nativism. And whenever nationalism plays out as a pastoral of power, it needs a hero of action as well as ideas. There he was, in varying avatars of maximum power: as an avenger of aerial adventurism; as the compassionate ruler who defied dogma to reach out to the marginalised; as the most engaging conversationalist of them all, never missing the uses of anecdotal personal history; and as the just king. The new nativism, built on national pride and a stronger sense of place and cultural identity, found in him the ideal Indian, someone far removed from laboratory-born cosmopolitanism.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

He played the role of "practical idealist" to perfection, without being overtly Gandhian though. When the blue- blooded Right wanted him to play an Indian version of a Reagan or a Thatcher, he was "practical" enough to realise that India was too poor a country, in spite of the growth rate, to build a regulation-free market economy. And he was not the compassionate conservative in the western mould either, for his ideology was rooted in Hindu nativism. It was often said that, when in doubt, even your loftiest capitalist would turn socialist, but the modern conservative, an apostle of the familiar rather than a worshipper of utopia, was never at home with socialism. Modi didn't turn socialist; he just reaffirmed that India was the countryside—and the wretched still lived over there.

The Modi Model stressed individual dignity in an unequal India. Here, too, biography was the equaliser. He empowered ordinariness in a country where political power often rhymed with inherited privilege. The Great India Story of the Davos man was a convenient exaggeration of progress. India was still a poor country, where the metaphor that mattered—and worthy of marketing—was not 'temple' but 'toilet'. Modi conversed with the poor—and they were all not the shirtless Hindus—as an ascetic who knew that power was a necessary condition for change. He was the One they, too, could be. Dreaming in dignity was the first stage of social transformation.

He struck a fine balance between being a moderniser and mollifier. Even as he deployed the abandoned idealism of the Indian socialist (who had miserably lost India), he played a nationalist-globalist who was supremely confident of his country's place at the high table. In the lazy comparative study of politics, he was portrayed as a strongman-populist like a Putin or an Erdog˘an. He was not the nationalist—or for that matter the nativist—who retreated from the world and took refuge in the make-believe of greatness. Modi's internationalism was unconstrained by ideology; it was marked by ideas of engagement. The "practical idealist" was at play again.

Modi, as man and idea, is a layered construct. The many become one seamlessly. The fire-breathing avenger as the Hindu nationalist for whom nothing is more sacred than the motherland; the compassionate reformer who has redeemed socialism from socialists; the moderniser for whom a religious identity is not subversion but the humanisation of secularism; the ruler who has shown that absolute power only enhances the individual integrity of its wielder; and the outsider who remains a permanent campaigner—what could have been a contradiction in the case of a politician as usual becomes a confluence of ideas as diverse as India in the story of Modi.

When change is as pronounced as the missionary zeal of one man, the debris too tells a story of what we had endured and where we have reached. The liberal crack-up, like the populist surge, may be the most written about topic of our time. I would still say the problem is not liberalism, which is perhaps the last tolerable ism left. The problem is the liberals. They refuse to leave the comfort zone of echo chambers and become part of the struggle for change. As the American writer Mark Lilla says, they have become losing evangelists: "Evangelism is about speaking truth to power; politics is about seizing power to defend the truth." Indian liberals have made themselves politically irrelevant. Transfixed by Modi the bogeyman, they refuse to see the social churn that has made Modi possible. All they wanted was a suitable hate figure to keep their conscience stirring in the echo chamber. They are joined in the debris by the Alternatives, sustained by either families or social fallacies, and united by the politics of anyone-but-Modi. When change is as historic as today, the debris of anti-Modi-ism reminds us how intolerant India has become of false arguments.

After winning the argument for change, Modi was remarkably modest in his victory speech. He alone knows, as always: tomorrow is another struggle.