The Meaning of the Mandate

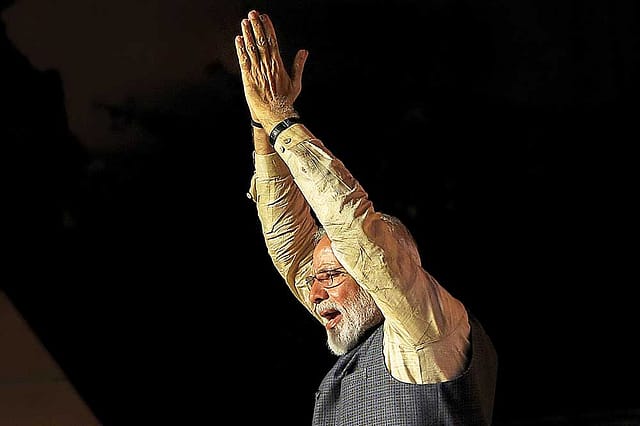

ON THE DAY HE WON THE SECOND TERM AS Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi's demeanor was like Arjuna in the Battle of Kurukshetra—composed yet confident. He seemed unprepared to rest on his laurels, his body language exuding the ambition of a man who is out to serve his countrymen to "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea", a lofty target that Alexander the Great had set for himself. In victory, the BJP supremo displayed a general's grace by congratulating his cadre for toiling in the scorching heat to ensure that they protected his honour. In the Indian political firmament, Modi proved that he simply had no peers, as this landslide of a second triumph reinforced. At a robust 68, Modi seemed to realise the enormity of his role and destiny.

As the results of the seven-phased 2019 Lok Sabha elections trickled in on the tense morning of May 23rd, showing an advantage for the BJP before it transformed into into a landslide victory for the ruling party, rival politicians who appeared on TV channels looked puzzled, even though they had asserted on previous days that exit polls projecting an NDA sweep were off the mark. Much to their anguish, the exit polls were slightly off the mark in the opposite direction: several of them trailed the BJP's actual tally, which far exceeded even the forecasts of a thumping victory by the ruling coalition leader. The saffron juggernaut was galvanised by a mammoth campaign that relied on the aura around its spearhead Narendra Modi. It was ably reinforced by an armada of volunteers steered by party president Amit Shah who came up with off-centre gambits to tap new opportunities, turn adversities into gains and dwarfed the opposition's messages and promises that failed to strike a chord with the majority of voters, especially lakhs of women and millennials making up a chunk of new voters.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

By the evening, as BJP workers congregated in thousands to celebrate Modi's victory, the skies thundered with lightning and rain as if Shiva himself was dancing a taandav of furious victory, uprooting trees along Delhi's boulevards as the Modi wave had done to his opponents.

Speaking shortly afterwards to euphoric party workers gathered at the BJP office in Delhi, Modi described his win as a "victory of democracy". To chants of 'Modi, Modi', the BJP supremo called himself a fakir (ascetic) and took the opportunity to thank the people of the country for filling up his jholi (bag), referring to the historic mandate for his coalition—he is the first non-Congress Prime Minister to return after a full term in office. Electoral feats don't end there: he is the first Prime Minister since Jawaharlal Nehru to secure consecutive majorities on his own; he is also the first Prime Mi nister since Indira Gandhi to return to power with an absolute majority for his party, just as she did in the elections held after the Bangladesh war of 1971 to the fifth Lok Sabha.

Though Modi took subtle digs at the opposition in his speech, he vowed to not work with any ill-will to anyone. He also urged his rivals to criticise him when he goes wrong. Modi, whom Shah called on the occasion as the "Mahanayak of Mahavijay" (the great leader of great victory), also pledged that he would not "do anything for himself but will do everything for the country". Disapproving of caste-based politics, he said that there are only two kinds of people: poor and those who help the poor.

For a consummate politician, Modi knows only too well that his voters see a message in each of his actions, even if it has to do with visiting a hill shrine for prayers and meditation. And now, the enormity of his consecutive wins of comparable magnitude confirms that Indian politics has shed its old inhibitions and acquired new dimensions. It may never be the same again.

From the start, it was an unequal contest. The 2019 election, which saw BJP neutralising myriad political dynasties and battering current players of caste-based politics to submission, brought to the fore the clever and imaginative use of organisational prowess by the party. All this was in stark contrast with Congress' relatively frail outreach bids and the failure of other rivals, including overrated regional contenders, to rise above conventional methods to pull in votes, even from their traditional vote banks that seemed to crumble as fresh trends buffeted the nation. The 2019 elections herald the dawn of an India born anew, where for the first time in its electoral history, there was animated talk about the consolidation of majority Hindu votes.

The BJP, on its own, won 302 (at the time of going to press) seats in the 543-member Lok Sabha, well past the magic figure of 272 required to form a government, and its allies managed 49. The Congress, which won 53 seats, again short of numbers to stake claim for the de jure role of the main Opposition party in the House, won no seats in 20 states and Union Territories. They include Delhi, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha, Tripura, Manipur, Mizoram, Daman & Diu, Dadra Nagar Haveli, Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Chandigarh, among others. The Grand Old Party of India, created in 1885 and which led the country's freedom struggle under the guidance of Mahatma Gandhi, managed to win only one or two seats in many other states. Congress President Rahul Gandhi lost from family bastion Amethi, which he, his family and a family friend had won in consecutive polls since 1980, except for a short-lived term. On the other hand, the BJP won more than 50 per cent votes in as many as 224 seats compared with 136 five years ago; the Modi-led NDA won more than 50 per cent votes in some 15 states and Union Territories, and ensured that it retained a large chunk—over 80 per cent—of its seats while Congress languished at 37 per cent. As the results confirm, the BJP poses a grave danger to the mere existence of regional parties in several states, including Uttar Pradesh where it decimated the Mahagathbandhan of Samajwadi Party (SP), Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) by winning 64 seats against their 15. In West Bengal, the saffron party cruised ahead with 18 seats from 2 in 2014, nipping at the heels of Trinamool Congress chief and Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee who won 12 seats fewer than 2014, winning 22 of the 42 constituencies. In Bihar, it won 17 and its ally, Nitish Kumar-led Janata Dal (United) 16 while Lalu Prasad's Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) drew a blank. Even in Telangana, the BJP won four of the 17 seats while the ruling Telangana Rashtra Samiti won only nine seats.

Endless Pursuit

MODI HAD KICKED OFF THE CAMPAIGN WITHIN days of it coming to power with an absolute majority at the Centre in 2014. Though there was enough and more of criticism of the Prime Minister—the first post-Independence- born candidate to occupy the top post—not interacting with the media through press conferences in the years that followed, Modi had made sure he communicated incessantly regardless, through online platforms such as Twitter, his own app, regular programmes like Mann ki Baat and well-timed addresses to the nation that outlined his vision and policies for the country.

While scorned by a section of the elite, his pronouncements were treated like gold dust by a much larger voter base, as the results of various elections over the past five years have proved. In fact, controversial topics such as the Rafale deal and setbacks caused by demonetisation were hardly discussion points in the elections this time around, as Open reporters were surprised to discover during their tours in various states. In Uttar Pradesh, which sends 80 MPs to Parliament, the largest by a single state, most people surveyed by Open contended that they treated their vote as one for Modi, not essentially for the local NDA candidate. Behind the tactic to transform the 2019 parliamentary poll to an election akin to a presidential one in which Modi was the sole leader and key contender to power, lay relentless hard work, craftily packaged federal schemes targeted at the poor and grand moves to garner the support of other socially, economically and politically marginalised groups.

Merging Class, Caste

FROM GORAKHPUR TO FAIZABAD AND AZAMGARH TO Allahabad, there was a popular Bhojpuri song that resonated through the bylanes, in this election: 'Aadha roti khayenge, Modi ko jitwayenge.' It is a variant of renowned singer Keshrilal Yadav's words 'Nun Roti Khayenge'. The song reflected the massive sway of Modi in Uttar Pradesh over a new social coalition that finally trumpedthe grand alliance of the Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) that had placed hopes in the advantage of caste arithmetic in the most populous state. It was a coalition of those at the bottom of the economic pyramid, irrespective of caste and community, both of which have been building blocks of politics for decades in the state. For the first time, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were in the thick of a transformative new identity politics that, breaking the powerful caste barrier, brought its poor on a single platform, as the 2019 election results confirm. The coalition comprised the poorest of the poor, a large section of who were Dalits and lower OBCs, who account for close to 30 per cent of the state's population.

This newly-formed social support base for the BJP included those who had voted for Modi in 2014. Its preference for Modi then was mainly fuelled by the credibility deficit suffered by the Congress-led UPA and the socio-political and economic domination of the Yadavs over other OBCs under Akhilesh Yadav and the Samajwadi Party. This time around, however, this group of non-Yadav OBCs and MBCs—besides all the marginalised, unorganised and economically weak—threw their weight behind Modi thanks to a plethora of common denominators transcending caste. The notable non-Yadav OBCs in the state include Saithwar, Bind, Gadariya, Nishad, Prajapati, Teli, Sahu, Hahar, Kashyap, Kachhi, Kushwaha, Rajbhar, Nai, Badhayi, Panchal, Dhiman, Loniya, Noniya, Gole Thakur, Loniya Chauhan, Murao, Fakir, Lohar, Koeri, Mali, Saini, Bharbhuja and Turaha. All of these groups have been successfully co-opted into Modi's new socio-political coalition.

Besides, most of them are beneficiaries of innumerable government schemes, Central and state, including low-cost housing, sanitation, free gas connections, power, healthcare and so on. The Direct Benefit Transfer scheme was the icing on the cake. In just five years, thousands of voters have thus been empowered with a transformed lifestyle unimaginable for decades. In field surveys, officials vouch, there were hardly any complaints from Muslims of any discrimination as it was feared by a section of potential beneficiaries. Unsurprisingly, Muslim anger of the kind seen in the past against the BJP, and especially Modi, is subdued this time even in Muslim-dominated seats.

This electoral tactic of carving out a vote bank among the poor was successfully replicated by BJP/RSS volunteers across the vast Hindi belt well prior to the elections as part of, what they affirmed, was Modi's inclusive governance that obliterated existing walls of social compartmentalisation. Gone are the days when Lalu Prasad could utter a catchy slogan like 'Swarg nahi diya, swar diya (didn't give you paradise, but gave you voice)', and win the backing of the backwards.

Such efforts of the BJP over the past few years, through the government as well as mobilisations by the party, brought into force a perception about Modi as a doer that began to click well. Brand Modi therefore became an irresistible proposition, especially among beneficiaries of the NDA Government's schemes that account for close to 220 million people. Interestingly, women form a nodal part of Modi's coalition of the poor across UP and the Hindi belt. Team Open's tours to the hinterland validate the BJP's claims that a section of Muslim women who benefited from the welfare schemes in north India tend to view Modi as a do-gooder though it is not sure whether that perception has translated into pro-Modi votes. Yet, such a perception among the minorities is gaining in traction.

As a result, such new coalitions engender a watershed moment in UP and effect a realignment in political affiliations. In 2007, BSP chief Mayawati spearheaded a new political inclusion movement in UP. Modi's idea of inclusion rests on both development and politics. Historically, there were four milestones so far in identity politics of the Hindi belt: The first was when the three peasant castes of Yadavs, Koeris and Kurmis formed the 'Triveni Sangam' with a view to rally other marginalised castes behind them in a movement for social justice prior to freedom. The move didn't meet with much success.

And then came the vigorous assertion of OBCs in Indian politics: in 1959, Ram Manohar Lohia was the first leader to demand empowerment of the socio-economically backward castes. Karpoori Thakur, in his second term as Bihar CM, introduced quotas for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions. The Karpoori Thakur 'formula' batted for a kangaroo quota for MBCs from the reservation quota for backward classes, checkmated by the powerful Yadav bloc on whose support Thakur, from the numerically weak Nai community, relied on. Then, in December 1980, the Mandal Commission submitted its report on reservations to socially and educationally backward classes to the Government. The subsequent Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi governments put the report on the back-burner. The report was finally accepted by the VP Singh Government a decade later, in August 1990.

The third attempt triggered much political churning. Mulayam Singh Yadav became chief minister of Uttar Pradesh in 1990. A few years later, he formed SP and became the unquestioned leader of the upper OBCs in the state. The Yadavs had become a powerful force, on the back, among other things, of the Mandal Commission. True, the transfer of power from the upper castes of UP to the OBCs was not smooth. But the empowered OBCs had come to stay on the political firmament across the country, radically altering social equations across north India.

Following this came the Dalit surge under the guidance of Kanshi Ram. As tensions mounted between the upper OBCs and Dalits, the latter came up with aggressive slogans like 'Tilak, taraazu aur talwar, inko maaro joote chaar'. Dalit politics came into its own in UP for the first time but the primary targets were upper castes, the Brahmin, Bania and Thakur. Mayawati was a persona non grata in the upper caste and upper OBC-dominated politics of UP in the beginning. But by 2007, she aligned with the Brahmins who took credit for her victory. Mayawati put them in seats of power far disproportionate to their numbers in the state and sold the act to her hardcore Jatav supporters under the slogan 'Sarvajan Hitay'. Incidentally, it was in 1995 that Kanshi Ram had decided to resort to social engineering to widen his party's base. The social engineering in 2007 allowed the highest and the lowest in the social order to ally to check the OBC upsurge. Some distinctive slogans of the day reflect the thinking in the BSP which transformed Mayawati from a leader of a few social groups to one of a broader cross-section of society, the hallmark of mature leadership. And Mayawati subsequently emerged as the biggest challenger to Mulayam Singh Yadav and OBC politics. As many as 139 of the 403 seats the BSP contested in 2007 went to the upper castes: 86 of these were Brahmins; the BJP lost this group's support in over 35 seats to the BSP. Mayawati could not have moved to Lucknow with the support of 17 per cent Muslim vote alone. The results were stunning. Mulayam Singh's SP fell to only 97 seats in the Assembly (down from 143 seats won in 2002), while the BSP notched up a tally of 206 (up from only 98 in 2002). She appointed Satish Mishra as the party's first Brahmin national general secretary and the powerful upper-caste face of the BSP regime.

Yet, Mayawati continued to draw from the Jatavs once she become chief minister, and the cracks between the Jatavs and the non-Jatav Dalits continued to widen, allowing the BJP more than just a foothold among the Dalit vote bank both in 2014 and in the 2017 Assembly polls. Mayawati has been unable to strengthen herself among the other Dalit communities since. With every election, the BSP chief has been gradually losing her hold over the Dalit vote bank in UP, a downslide that has continued to the advantage of Modi and his powerful new alliance among the castes considered lowest on the social pecking order. Without doubt, these elections show that the BJP has gained enormously from the goodwill it has generated among the poorest of poor who had reposed faith in it.

Mission & Ambition

TARGETING THE REAL POOR IN ORDER TO OBLITERATE ruses that politicos employ to stay in power by appealing to clan-like sympathies was followed up with hard work that required utmost devotion from committed cadres. Selling Brand Modi topped the priority in the goal towards a second term and a spectacular win, and almost equally crucial was making inroads into uncharted territory, and in the process expanding the party as a well-oiled machinery to take on challenges as daunting as pursuing organic growth as well as tying up effective alliances in the south, the east and the Northeast. While electoral forays into the south and Northeast are well known and documented, efforts to secure a base in West Bengal where the BJP didn't seem to have a strong chance, started in right earnest days after Mamata Banerjee won the state elections in 2016. BJP President Amit Shah has since made 84-odd trips to the eastern state, starting with the most difficult of turfs for the BJP to make a political dent: Naxalbari in Darjeeling district from where extremist Leftist movement of Maoism originated in India in the late 1960s. Shah also held numerous parleys with senior RSS functionaries and BJP leaders and point persons in the state to chart out a growth plan. This bid was in line with the resolve by the party to expand to 120 new Lok Sabha seats where the BJP didn't have any flicker of hope some five years ago. Talking to Open shortly after the grand victory in the Uttar Pradesh state elections in 2017, Bhupendra Yadav, general secretary of the party, had said that the new pastures for the Hindu nationalist party would include Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, West Bengal and several states in the Northeast. "Certainly, on the list of our new targets are Andhra Pradesh and Telangana," he had averred, emphasising that a "lot of work" was being done in these turfs by the party, either on its own or with allies. At that time, the BJP was in power in 17 states that are collectively home to two-thirds of the country's 1.25 billion people.

For his part, the BJP president made it a habit to closely survey seats where the BJP was present but had never won, besides high-profile seats of top-notch opposition leaders. For example, in Guna in Madhya Pradesh, when Shah realised that the Congress candidate had overwhelming support from a region called Ashok Nagar, he encouraged party workers to work exclusively in that terrain. The idea was to go the whole hog in pursuing growth for the party. Till date, the BJP has 110 million members, making it one of the largest political parties in the world.

Such all-out efforts across the country to fight to the finish became a game-changer for the party. Presently, Shah recruited over 3,800 full-timers to work in difficult areas and trained them to connect with people across class and caste. He also insisted that they share meals at least once a week with an underprivileged family to build solidarity and cement ties with people from such backgrounds. The efforts proved to be fruitful, indeed.

By the time he faced the 2019 elections, Shah felt more comfortable than ever. Besides a record number of party workers, he also had hopes from 220 million beneficiaries of the federal welfare schemes. He was confident of wooing 330 million voters to his party's fold; in comparison, the BJP won 170 million votes and managed 31 per cent votes in 2014 to cruise itself to an absolute majority on its own, for the first time a party did so since 1984. Shah tells Open in an interview: "I was fighting the election in my own turf." As with the new base of the poor, he notes, "We were assiduously cultivating a vote bank. We created it from those who were either aligned with the Congress or the Left. And we did it without hurting the interests of our traditional vote banks."

Interestingly, three issues – inflation, corruption and secularism – were not topics of concern in this election. Inflation had been a major poll issue since 1957; and since the time of Indira Gandhi, corruption had invariably been a subject; secularism was a perpetual slogan for a long time, especially since the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJP's predecessor) made decent gains in north India in the 1967 elections to the fourth Lok Sabha.

The BJP leadership also had plans at the drop of a hat for newer problems, not merely long-term plans. For instance, following the setbacks in the three Assembly elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, concerned party leaders got into a huddle with Shah to discuss ways to troubleshoot and turn things back in their favour ahead of the General Election. It emerged from a meeting on Chhattisgarh that BJP had earned the wrath of some caste groups that felt they were not paid their due in allocating seats. Reparative measures were taken on a war footing. A particular caste group called Sahu and other tribals were immediately 'appeased' and their grievances addressed besides denying seats to incumbents. Similar measures were taken in Madhya Pradesh to address such worries. In Rajasthan, the central leadership of the party made sure that Gujjars, Jats and Meenas were well-represented to avoid any erosion of votes. As luck would have it, the BJP has surged ahead in these states in the Lok Sabha polls.

BJP, formed in 1980 as a successor to the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, has often worked towards championing the cause of the Hindus, but several Hindu groups still were politically inclined towards backing other parties like the Congress. In that context, the BJP had a lot in order in terms of winning support from a large section of Hindu civil society that includes various sects, saints, pilgrim centres, temples and so on. In fact, the idea of extending the influence of the BJP to these influential entities had struck Shah when he and his wife were on a pilgrimage shortly after a court order that disallowed him entry to Gujarat. By 2013, he had visited some 40 mutts in that long tour discovering India. He came to realise on becoming president shortly after the BJP was elected in 2014 that the party had to reach out to 7,600-odd mutts and centres that had inherited the legacies of saints of yore, including Kabir, Sant Ramdas and so on, besides those of Dom Rajas who burn the dead in Varanasi. Presently, Shah and his team began the endeavour to establish links with them. It was done systematically and with perfection. Very soon, the BJP was able to make friends with people who had a great following among various class and caste groups, including those of Yadavs of north India and Matuas of West Bengal, a Scheduled Caste comprising 17 million to 30 million, according to estimates.

It was with the view of attracting new segments of voters to the BJP that Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his Lok Sabha campaign from the border constituency of Bangaon and met 'Boro Ma', the matriarch of Matuas, who were traditional Trinamool Congress voters. In fact, Modi, in the fallow years after he was 'boycotted' by mainstream media, had done this on his own terms as Gujarat chief minister, befriending various religious sects to bypass the media and still reach out to a great chunk of people through influential figures. It also gelled well with the BJP's strategy of breaking caste affiliations that kept political parties afloat and dominant by wooing communities that had felt left out in the social engineering and political empowerment exercises of the past.

Closer to the elections, the BJP realised, to its delight, that the warmth it had for such groups was mutual and useful.

The New Matrix

JUST AS ASPIRING INDIANS WHO BROKE OUT OF BPL status looked up to a strong leader to deliver and the poor who felt obliged thanks to the much-needed social security they were provided with, the dominant theme in this election was the hope for more if the Modi Government continued for an other term. While the opposition Congress appeared to squander away chances for alliances in crucial states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bengal, and announcing welfare schemes that looked like a knee-jerk poll gimmick, the BJP was able to dominate debates that included the Balakot strikes on Pakistan. Chandana Bhakt, a homemaker from Singur which falls in the Hooghly Lok Sabha constituency, had told Open that her family, traditional TMC voters, would vote for the BJP this time around. She was upbeat about the "befitting" response to Pakistan's misadventures in Kashmir. She also had another grouse, she said in an interview: "Hindus haven't been treated well enough by successive governments." Open correspondents had found while such display of Hindu identity was not uncommon in private earlier, it was increasingly becoming a publicly-voiced opinion in several states in India.

As Shah said, the perception about Modi as a strong leader who deserves another term in power runs deep, contributing to this emphatic win. In Uttar Pradesh's Bansgaon, Ashwini Kumar, a dealer in building supplies, shared the view that that the Modi Government had done a lot for UP. "I had voted for other parties in the past. But now that we are more aware of what our leaders are doing, we are convinced that Modi is the leader to trust. Earlier, people were not very aware of politics, but now thanks to TV and social media, people have become intelligent," he said.

In Chandigarh, for instance, even JK Khattar, who averred to be voting for the Congress, said that he was doing so by force of habit and that most people he knew were voting for the BJP because they love Modi, not the local BJP/NDA candidate. Modi had appealed to voters that a vote for the lotus symbol was a vote for him directly. "That is the advantage that the BJP had. Local factors were hardly a concern in the elections in many places in the country. Modi has no rival who could challenge him and his party made the most of that appeal," Khattar told Open. In Deoria in Uttar Pradesh, Parmendar Bahadur Sahi, a banquet-hall manager was impressed with the BJP's "positive intentions"—which for him meant that BJP stood with the poor of all castes, buttressing the argument that BJP while wooing lower castes managed to keep its upper-caste loyalists happy.

A Study in Contrast

PRAVEEN CHAKRAVARTY, WHO HEADS THE CONGRESS' data analytics department, said sometime last year that Modi is a one-term Prime Minister and repeated an argument he had made in 2014—that the electoral outcome of 2014 was 'a complete outlier and unrepeatable'. He used the famous expression 'Black Swan moment' to speak of Modi's victory. He poked fun at what some pundits used to refer to as his 'invincibility'.

Chakravarty is an honourable man, but his statements and forecasts have been proved wrong. For someone very close to Rahul Gandhi, his line of thinking probably reflects what the Congress party was thinking—and therefore it isn't wrong to assume that the main opposition party had underestimated the challenges it faced in taking on its powerful rival. That the Congress missed the plot was also evident from its overestimation of the Priyanka Gandhi impact, with some suggesting that she being made the in-charge of eastern Uttar Pradesh under which fell Modi's seat of Varanasi, would hurt the BJP. The logic was that by pitching her in the region, the Congress could eat into the upper-caste vote base of the ruling party. The calculations, now it is clear, have gone awry, as is evident from the resounding defeat of her brother and Congress President Rahul Gandhi from Amethi, a family pocket borough, to Smiti Irani of the BJP.

It requires no knowledge of game theory to realise that the Congress had grossly underestimated the strengths of the BJP, Modi's popularity, the network of its key opponent and its own weaknesses. Rahul who lost in Amethi will make it to the Lok Sabha only because he also contested polls from Wayanad in Kerala. Not only was 2014 not a Black Swan moment, but Modi also improved his 2014 tally this time around and made inroads into new turfs. It comes as no shock then that several renowned Congress leaders besides Rahul suffered a humiliating setback at the hustings. They include Congress veteran Mallikarjun Kharge, often referred to as 'solillada saradara' (a leader without defeat) in Kannada, who suffered his first defeat in this election; Sheila Dikshit, the longest-serving Delhi chief minister; Bhupinder Singh Hooda, former Haryana chief minister; Harish Rawat, former Uttarakhand chief minister; Ashok Chavan, former Maharashtra chief minister; Sushil Kumar Shinde, former Union Minister; Veerappa Moily, former Union Minister; Nabam Tuki, former Arunachal Pradesh chief minister; Mukul Sangma, former chief minister of Meghalaya; and Digvijaya Singh, former chief minister of Madhya Pradesh.

Among the 11 Congress dynasts who fought the election, including Rahul Gandhi, only two bucked the trend. Jyotiraditya Scindia, Congress leader and scion of the Scindia royal family, Jitin Prasad, Milind Deora, Lalitesh Tripathi, Vaibhav Gehlot, Sushmita Dev, Bhavya Bishnoi, Priya Dutt and Deepender Hooda all lost. Those who managed to win are Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Kamal Nath's son Nakul Nath and former Assam Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi's son Gaurav Gogoi. From other opposition parties, notables who bit the dust include HD Deve Gowda from Tumkur, Mehbooba Mufti from Anantnag and Kanhaiya Kumar from Begusarai.

A lot of theories will be bandied now about why the Congress failed to unseat Modi based on hindsight wisdom. There were still indications for all to see that the Congress party seems to have missed, adopting an over-confident mode of campaign. One of its spokespersons has now admitted that its failure was thanks to poor organisation, which its president and other leaders had said were in good shape until May 22nd. In comparison, it is no secret the BJP had relied on continuous feedback from the lower rungs of the party, ensured seamless communication between select grassroots-level workers and the top leadership, and distributed tickets after much soul-searching and discussions. As regards the rigour behind arriving at decisions, Shah himself told Open that except in the case of 12 leaders who include Modi himself, Rajnath Singh and so on, the parliamentary party of the BJP spent 86 long hours to finalise other Lok Sabha candidates. "Each and every seat was thoroughly discussed," he said. Tickets were denied to unpopular leaders and top- level functionaries of the party were given the charge of choosing winnable candidates based on local feedback. The party also kept the RSS in the loop to make sure there is total coordination with the parent organisation who complemented the efforts of booth-level workers.

The BJP, which sees the national security plank as a mere value-add in the elections held this time, has continued to make a presence in new states, the most important being West Bengal. Five years ago, TMC had won 34 of 42 Lok Sabha seats while Congress won four and the CPM and the BJP, two each. The rise of the BJP in the state, replacing the CPM as the main Opposition party, has been rapid. Historically, Bengal is one region in India where the roots of Hindutva politics run deep thanks to a raft of reasons. The state is home to various revivalist movements that overlapped with reformist ones more than a century ago. The long-term influences of the 1905 partition of the province largely along communal lines cannot be ruled out. Add to that hostilities triggered by bloody communal riots that crippled Bengal in the run-up to the second partition of the province when the country became independent in 1947 and East Bengal became part of Pakistan. Wounds tend to fester through word of mouth and propaganda. Open had reported earlier that the BJP had been improving its vote share in local polls in the state thanks apparently to the RSS' long-term work, especially in the tribal belt and Hindi-speaking areas. This year's campaign saw pitched street battles between the TMC and BJP cadres in a state known for political violence and quelling of Opposition with the use of police. Recently, a statue of Bengal's legendary reformer and educationist Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was vandalised during Shah's Kolkata rally. The Election Commission ordered restrictions in campaigning in the state the day after the incident.

The greater tragedy that perhaps awaits TMC is what has already happened to the Left in West Bengal. The CPM-led Left Front, who had ruled the eastern state for straight 34 years until Banerjee came to power in 2011, won not even a single seat in the state this time. In Tripura, where the CPM had won both the seats—Tripura East and Tripura West—last time, it lost both. In these seats, the CPM was pushed to the third position. In Kerala, where a CPM-led government is in power, the party won only a single seat out of 20 Lok sabha seats and the rest were cornered by the Congress, in a major consolation for the latter. The rise of Modi also meant that the Left has been on a decline. Tripura has a BJP government and though Kerala is an outlier electing no BJP candidate to the Lok Sabha ever, the Left parties are on the wane nationally. From 43 seats in the Lok Sabha in 2004, the CPM was reduced to nine in the last Lok Sabha. In 2019, it won three seats including two seats it secured in Tamil Nadu thanks to an alliance with the winning DMK. Professor Sumantra Bose of London School of Economics tells Open, "What a tragic fate for the CPM, which until the panchayat elections of 2008—that started its downslide—had dominated rural West Bengal, an 80 per cent rural state, for 30 years. The CPM has abysmally failed to provide an effective opposition to the post- 2011 Trinamool regime in the state which from 1977 to 2009 gave the party its limited clout in national politics, and post-2014, it has ceded that Opposition space to the BJP."

With the BJP now looking to replace TMC in West Bengal and storm into new turfs, the political fortunes of many others—including TDP's Chandrababu Naidu—look extremely bleak. In Odisha, where the BJP has made significant gains, the party hopes to crack the winning code next time.

With Modi riding a wave of immense popularity that is on a par with the 1950s India dominated by Nehru, rules of engagement in Indian politics and society are set to change further and in a way that is difficult for pundits to gauge. That various loud slogans raised in this election turned incongruous with the aspirations of the masses, confirm just that.

As of now, Modi, who wears his common man's credentials on his sleeve, continues to be in the saddle in the world's largest democracy that hopes to become a global superpower, and comfortably so.

Also Read