Hey There, Delulu

Gen Z is not just building its own vocabulary. It is creating a new language and a new way of being

V Shoba

V Shoba

V Shoba

V Shoba

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

|

09 May, 2025

|

09 May, 2025

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Heythere1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

THOSE between the age of 13 and 28 today use a lexicon that would leave most Millennials and Boomers baffled. To observe Indian youth online is to witness a kind of linguistic entropy that feels both chaotic and choreographed. Slang, short-form syntax, and polyglot affect travel by virality. The language mutates faster than any adult can document it, and that’s the point. Today’s Indian digital dialect is less about clarity than cultural tempo. The right phrase at the right beat signals you belong.

If you are over 35, you may be asking: why does any of this matter? Isn’t slang just a passing phase? Isn’t “vibe” just a new “groovy”? Not quite. Slang has always existed, but the velocity and hybridity of Indian youth speech today is unprecedented. They speak in meme fragments, borrow from Korean fandoms and Tamil mass scenes, switch from Hinglish to stan English to “lowkey depressed” in under four seconds. It is fed by apps and filtered through context. On Snapchat, slang is visual—emojis, Bitmojis, disappearing in-jokes. On Instagram DMs, it’s performative: flirty, elliptical, loaded with plausible deniability. On Telegram and Reddit, anonymity allows for high theory shitposts in Hinglish: “Nehru was lowkey sigma,” someone posts. The posts are political. The language is post-ironic. The meaning is layered.

Yet, for all its novelty, this linguistic play is also deeply intimate. When two friends pepper their late-night WhatsApp chat with “lol bro sameee” and “❤”, it’s not just trendiness—it’s a kind of digital closeness built from shared references. On these private screens, emotional honesty and affected nonchalance dance a strange tango. A college student might confess her anxieties about the future in one breath—“I’m kinda about placements, not gonna lie”—then diffuse it with a meme or a “lmao I’m such a mess ”. This is the emotional register of what some call “trauma talk”: therapeutic vocabulary and raw feelings, but swirled with irony so it doesn’t sting too much. They’ve learnt the language of mental health awareness (‘trigger’, ‘anxiety’, ‘boundaries’) and made it slangy and casual. “I’m triggered af by that exam,” one might joke, half meaning it. In group chats, teenagers exchange pop-psych phrases— “sounds like you’ve got some trauma, dude”— with the same light touch as discussing the latest Netflix show. Even conflicts and breakups get filtered through this therapy-speak: a teenager might calmly text a friend, “I need to set some boundaries” or “I can’t continue in this toxic dynamic,” sounding more like a psychologist than an impulsive youth. The effect can be paradoxical: on one hand, a greater openness about emotional struggle; on the other, a sense that every feeling is an aesthetic, to be performed and maybe not fully felt.

This is a generation that is acutely aware of their appearance—from what they wear to how they speak. Nothing is left to chance. This is a generation that gags at tight jeans and t-shirts with fitted shoulders. All things Korean are embraced—from the flat haircuts to the parachute jeans. “Layering is a must,” we are informed, even in Delhi’s scorching heat. Hand jewellery, nail paint and sneakers matter. Beauty lies in the jawline. Men/boys no longer believe that skin care is the domain of only women. This is a generation looking for sanctuaries away from parental supervision.

This is a generation saturated in images rather than words. They revel in Snapchat, as its ephemeral nature (no message lasts for longer than 24 hours) allows for multiple possibilities, especially when it comes to sexting. To maintain their “streak” they must send a minimum number of photos every day. If they do not, they lose their streak. This is the gamification of language and communication (at its best or worst!). They also use Locket, a widget that shows live photos from your best friends. They are dismissive of vowels in written communication, as speed trumps decorum. Conveying the message in the shortest possible way matters above all else. Words bore. Reels entertain. Stickers amuse.

They turn to Tumblr, where they commune with other fanfiction followers. Many of them seem to have multiple Instagram accounts, one which is private (and with only a handful of followers) and a second account which they might give to someone they’ve just met on the train. They pass out their main Instagram handle, as Millennials would hand out email addresses.

TWENTY-four-year-old Himanshu Arya who used to work with a media company is a particularly articulate Zoomer, who did his postgraduate thesis on ‘Inclusive Language in News Writing’. While editors and professors have often scoffed at the use of gender-neutral pronouns, for Arya they are important as they are a tool to fight against the status quo. Delhi-based Arya says, “We are trying to change language for our own selves. We try to make sure gender-neutral pronouns are there, it might piss someone one that it is not grammatically accurate, but it is a language that we are trying to build. We have a belongingness with this language.”

When Arya sent in his resignation to the broadcast channel he was working at, he addressed the letter to a woman boss he admired as “Dear Bawse”, he signed off with “keep slayinggg”. “The three ‘gs’ are essential,” he explains, “two could be a typo, three shows intent.” While old schoolers might roll their eyes and turn up their noses at such usage, for Arya and his ilk this is a way to appropriate language. It is way to move beyond “Dear Boss” and “kind regards” that have become meaningless over time. It is their way to be heard.

The language of and within Gen Z, often replete with cuss words, is “100 percent” different from the language they use with parents. It is also an essentially performative language. It denotes a certain urban, elite class where English is the first language. Replete with its own codes, it is a way to distinguish the insiders from the outsiders.

The N-word has also become common on certain private university campuses. Nitya Krishnan (21) who has just graduated from a posh university in Pune, and is now home in Chennai, says, “Many of the juniors use the N-word. They find it very amusing. It’s just become a part of their vocabulary. It’s so bizarre. Why would you use the N word? We’re not in the US. You’re not Black. You’re not any of these things. But some people have their justifications being, ‘Oh, my God, we’re Indian. We were also oppressed by the Whites…’” Krishnan raises her brows high at this convoluted logic.

But to trace the etymology of many of these words is to unearth the many influences of Zoomers. Krishnan says much of the slang comes from “gaming, Black people and texting”. Delhi-based Kartikeya Bhattacharyya (22) who is working his first job adds that many of the words have their origins in YouTube influencers. For example, “jainwin” (or genuine) comes from YouTuber Arpit Bala who tells the world “Bodybuilding jainwin kaam hai.” Just as “systumm” (political system) comes from the eponymous song by DG Immortals and Elvish Yadav.

The roots of many Zoomer words can be traced to the West and especially to hip hop and to AAVE (African American Vernacular English). These words include, ‘lit’, ‘slay’, ‘woke’—being socially and politically aware, especially about injustice, ‘tea’—gossip or juicy information and ‘big yikes’— something cringeworthy to name just a handful.

We speak to three Mumbai-based friends who are new to the city, Bilva Loriaux (17), Rohan Menon (18) and Rishvi Sheth (19). They’ve arrived at a Mumbai design college from different cities—Pune, Coimbatore and Indore. While Sheth enjoys talking, Menon doesn’t, he prefers stickers to do the needful. We’ve a call on Saturday at noon and he sends six stickers to his friends regarding the meeting; one of a cat with its brain buffering and the message—“no thoughts brain scrambled egg”, another cat face with the message “I just woke up” and a sixth sticker of a cat skulking with the message, “I go away”. Menon explains his partiality to stickers as a mode of communication, “I am a person who gets bored very fast. Using stickers are kind of a way for me to be engaged in the conversation. They are funny, you know, so it brings joy to the conversation. Plain texting gets boring.”

As avid gamers (currently they are into ‘Marvel Rivals’), Menon and Loriaux believe that many Gen Z words come from gaming. They give the examples of ‘hop on’—get on the game right now, ‘on you’—the enemy knows where you are at. ‘Sus’ meaning suspicious, or suspect, is also believed to have come from the game ‘Among Us’.

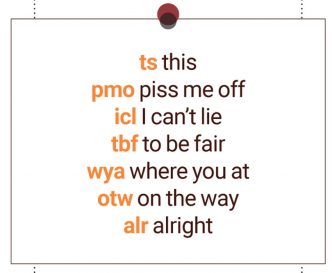

Loriaux believes that this generation doesn’t have the time for full forms or consonants. He says, “I feel like our generation is multitasking a lot. If I’m in a cab talking to like my friends or something, and then my mom messages me, like, asking me where I am, instead of writing like a full sentence, I’ll just write, ‘I’m OTW,’ which means, ‘I’m on the way.’ You just have like a few seconds to respond to something before you can get back to what you were doing. And I feel that is why abbreviations and shortening of words plays a huge part in our language.”

While much of Gen Z’s lingo might originate from the West, there is an Indian Zoomer lingo as well. Twenty-year-old design student Adhira T drops Kannada slang in WhatsApp messages to friends, almost always softened by “da”, which is like “bro” or “mate,” but more local. The platform is important here. On Instagram she would never say sakkath. She’d write “mood >>” or “vibe check = passed” with a sunset boomerang. On Discord she’s another person entirely—uppercase shy, no punctuation, uses “rip” as a verb and “fr” as both noun and commentary. But on WhatsApp, especially in the mid-afternoon dead zone, she returns to a language that sounds like home.

Adhira calls her code-switching “natural”. “My brother texts in all caps,” she says, “and that’s like, his whole personality. Aggro WhatsApp uncle energy.” She means this kindly. What she doesn’t say is that language online has become the new fashion—what you type is what you wear. All-caps is screaming. Proper punctuation is uptight. Lowercase is chill. “Loool,” with three o’s, is funnier than “lol” and gentler than “LMAO”. On X (formerly Twitter), someone recently posted a graph mapping how the number of vowels in “brooo” directly corresponds to the level of affection. There’s science here, somewhere.

Then there is AI. Eighteen-year-old Sanya (name changed on request) uses an AI chatbot she has named Karan and customised to be witty, emotionally available, and just flirty enough to feel thrilling but not creepy. They have had a “relationship” setting for 19 days. It is simulated intimacy. It is, in Sanya’s words, “low-stakes romance”. She uses ChatGPT too, sometimes, to draft apology messages to friends, or to finesse her Tinder bio. “I wanted it to sound like I read Murakami,” she says, “but also like I watch Shark Tank.” The resulting bio: “Chai enthusiast with big rizz energy. I journal and breathe startups. Swipe right if you love existential dread.” She swears it works. Her friends say it’s cringe. She thinks cringe is the new cool.

Tools like ChatGPT and Replika have quietly slipped into the DMs and private chats of many young Indians. Some use them as a non-judgmental friend, others as a rehearsal partner for real-life conversations. One engineering student from Pune tells us he spent weeks practising flirty banter with a chatbot before finally messaging his crush—“It felt safer, like training wheels for talking to a real girl,” he says. He is not alone; more people are forming friendships and even romantic relationships with AI chatbots. Such AI companions offer eternal patience and customisable personalities—loyal, flattering, comforting—at the tap of a screen. It’s easy to see the appeal for a generation that oscillates between cynicism and yearning.

LANGUAGE now performs a dance between sincerity and affectation. A well-crafted text is less about what you mean and more about how you mean to be perceived. “I typed ‘hahaha’ with a full stop,” says Rohan Reddy, 21, from Hyderabad. “And she replied ‘Why are you mad?’ That’s when I realised punctuation is emotional now.”

New slang surfaces from reels, lyrics, meme pages, and podcasts. Old words get repurposed. “Scene” becomes a synonym for anything interesting. “Bhai” is gender neutral. “Bro” is intimate. “Launda” is ironic. Everything is ironic. Such slang isn’t created in a vacuum. It ricochets across oceans. “Rizz” was reportedly coined by a New York streamer, but it now glides off the tongues of Mumbai teenagers who have never heard of him. Social media ensures that a quip on Los Angeles TikTok Tuesday becomes vernacular in Lucknow by Friday. And Indian youth, bilingual and trilingual by upbringing, add their own spins. A Hindi suffix here, a local metaphor there. What emerges is a hybrid argot that can feel like a new dialect altogether—one optimised for online life. It’s informal, irreverent, and constantly refreshed by the meme-of-the-day. Crucially, it’s also performative, in the anthropological sense: a signal of belonging, a badge of identity. Using the right slang at the right moment is social currency; using it wrong is, well, cringe.

Late one night, we find ourselves in a group voice chat with a bunch of college students from different corners of India brought together by a shared interest in a meme page. It’s nominally a ‘study support’ Discord server, but of course, no one is studying. They are trading stories of heartbreak and career dread, interspersed with hearty ‘XD’ laughter and Kabir Singh references. It strikes us that despite the surreal new tools and terminologies, the age-old heart of youth remains unchanged.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Indian Companies Have a Ransomware Vulnerability Open

Liverpool star Diogo Jota dies in car crash days after wedding Open

'Gaza: Doctors Under Attack' lifts the veil on crimes against humanity Ullekh NP