Manmatha Nath Dutt—Sanskrit and English

Manmatha Nath Dutt possessed formal degrees. From 1891 to 1900, he described himself as MA from 1901 and "Shastri" was added. Since "Shastri" was added later, it was a separate degree.

The upadhi (title) "shastri" connotes different things. Today, the nomenclature is "Shastri" for BA (in Sanskrit), "Acharya" for MA, "Vidyavaridhi" for Ph.D and "Vachaspati" for D.Litt. Lal Bahadur Shastri's surname was not Shastri. It was the upadhi. His surname was Srivastava, which he dropped because of caste connotations. Subsequently, when he did a BA (not in Sanskrit) from Kashi Vidyapith in 1925, he obtained the title of "Shastri". Today, there are Sanskrit universities where BA confers the title of "Shastri". In Calcutta, Sanskrit College was established in 1824, with an affiliated feeder school. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was Principal from 1851 to 1858. Before Vidyasagar, only brahmana students could join Sanskrit College. Manmatha Nath Dutt was a kayastha. During Vidyasagar's tenure as Principal, admission rules were changed and non-brahmana students could also enroll. Subsequently, Mahesh Chandra Nyayratna Bhattacharyya (1836 – 1906) was Principal from 1876 to 1895 and he introduced upadhis. Note that University of Calcutta didn't have a Sanskrit department until 1907. Therefore, when Manmatha Nath Dutt became Shastri in 1901, MA degree would have been awarded by University of Calcutta, but the title of "Shastri" would have been conferred by Sanskrit College.

Having obtained the "Shastri" title, one had the option of dropping the original surname. Other than the Buddha book, Manmatha Nath Dutt never dropped his original surname. Sivanath Sastri was author, historian, educationist, social reformer and much more. Sivanath Sastri was born Sivanath Bhattacharya and dropped the surname after obtaining the title "Shastri". A footnote in his autobiography tells us how he obtained the title of Shastri. Sivanath Bhattacharya passed the MA in Sanskrit examination through University of Calcutta and stood first in the first class. That is how he obtained the upadhi of Shastri. He studied in Sanskrit Collegiate School and Sanskrit College. That's exactly what happened with Haraprasad Shastri (1853-1931), born as Haraprasad Bhattacharya too. That conclusively establishes Manmatha Nath Dutt studied in Sanskrit College for his MA in Sanskrit, was first class first and obtained the upadhi of "Shastri". This was a remarkable accomplishment.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Many of the Hatkhola Duttas were interested in writing, printing and publishing, except they typically did it in Bengali, not in English. Manmatha Nath Dutta's forte was the English language.

Here is a long quote from his introduction to the translation of Valmiki Ramayana: "The immortal epic of Valmiki is undoubtedly one of the gems of literature, indeed, some considering it as the Kohinoor of the literary region, which has for centuries, and from a time reaching to the dim and far past, been shedding the unparalleled and undying halo upon the domain presided over by "the vision and the faculty divine."…Bharata, stoutly and persistently declining, despite the exhortations of the elders and the spiritual guides, to govern the kingdom during Rama's absence in the forest, and holding the royal umbrella over his brother's sandals, are personations of the ne plus ultra of fraternal love, and consummate and perfect ideals of their kind….Truly of the Ramayana it can be said in Baconian language that it has come home to the business and bosoms of all men…Ravana is remembered not only in consequence of the prominent part he plays in the Ramayana, but also on account of his famous advice to Rama immediately before death, namely that the execution of evil projects should be deferred, but that good ones should be promptly executed, a very sage counsel doubtless, answering partially to Macbeth's observation on hearing of Macduff's escape: "… From this moment/The very firstlings of my heart shall be/The firstlings of my hand…."….Ah, who can say how many women have turned away in the budding prime of youth from the primrose path of dalliance, and have in preference followed virtue, who alone is truly fair…In it (the Ramayana), cosmogony and Theogony, the genealogies of kings and princes, of human and extra-human beings, of Ashuras and Danavas, of Jakshas and Gandharvas, and Shiddhas and Charanas; folklore and anecdotes and legends, and stories half-mythical and half-historical; descriptions of cities existing at a period long anterior to the age of Troy and Memphis, and the chronicles of kings that reigned before Priam and Busiris, all these with others too numerous to enumerate, have been woven into the mighty web and woof of the magic drapery evolved by the potent art of Valmiki…..Nay, we can perhaps safely go so far as to assert that very few amongst those Western scholars who have devoted their lives to the study of Sanskrit literature, have been able to enter into the spirit of that part of its vocabulary in which are couched those peculiarly Hindu ideas and sentiments that constitute the unique genius of the people. To translate, therefore, such a work as the Ramayana from the dead and indefinite Sanskrit into the living and real English, is like unearthing a fossil and inspiring it with life; or rather like transferring a light from a bushel in which it has been hidden, to a mountain-top, so that men may behold it and the surrounding objects by help of its grateful rays. Surely, to render a work from a dead tongue into a living language, and specially such a language as English with all its resources, is literally taking it from its narrow and circumscribed sphere of influence and placing it before the world at large—in fact, making it the common property and heritage of all mankind." The Introduction ends with an invocation. "Let us, accordingly, begin by invoking Him whose presence can convert the foulest and the most unclean spot, pure and clean, "like the icicle that hangs on Dian's temple," or the hearts and aspirations of the Vestal Virgins, or pious saints ever engaged in meditating the Most High."

In this longish quote, there is quite a lot that is easy to miss. "The vision and the faculty divine?" That's William Wordsworth in 'The Wanderer'. Ne plus ultra? That could be from anywhere. After all, it does mean the ultimate example. But I think it was because Coleridge wrote a poem titled 'Ne Plus Ultra'. 'Business and bosoms of all men' is from Francis Bacon's The Epistle Dedicatory. Macbeth is obvious. But Shakespeare features again through Coriolanus. Priam and Busiris, in the same breath? Might be coincidence. Or, was this because of a familiarity with Edward Young's (1683-1765) plays? I can understand Priam or Busiris separately. But linked together, it suggests Edward Young to me.

Gleanings-II has the story of Rani of Argal, with verses thrown in. "Mother of mighty rivers/Adored by saint and sage;/The much-loved peerless Ganga,/Famous from age to age." "The fear was in her bosom/The Rani shed no tear;/And her eye resentful sparkled,/As the enemy drew near./She stood there brave and scornful,/Her maids by her side;/And with undaunted calmness/The Ajodhya's chief defied." The Rani shouted out, "Are there no Hindu clansmen,/No Hindu brother here,/To whom a Hindu mother/And a Hindu wife is dear?/If such there be, arouse ye,/Stand forth, stand forth to aid,/By the gods I adjure you,/My curse on you is laid." "But all rejoiced to see her,/And with one voice did tell/How the Rani and her maidens/Had fought so brave and well." To me, the influence of Thomas Babington Macaulay's Horatius seems palpable.

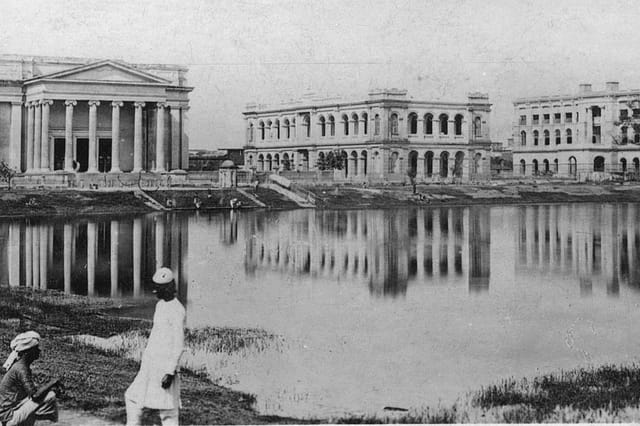

The picture that emerges is of an individual with an intimate knowledge of English literature, in particular, poetry. Before Shastri upadhi in Sanskrit, Manmatha Nath Dutt obtained an MA degree and this must have been in English. This cannot be proved conclusively. After all, one can study Bengali or Philosophy and pick up knowledge of English. But English seems likely. Where might he have studied in 1880? A few years later, it might have been Scottish Church College. But in 1880, Scottish Church College was still Duff College. It became Scottish Church College in 1908. It could have been Vidyasagar College, which around 1880, was still known as Metropolitan Institution. Manmatha Nath Dutt is unlikely to have studied in educational institutions started by Western missionaries. That pins it down to Presidency College, now Presidency University. This was started as Hindu College in 1817 and renamed Presidency College in 1855. His BA and MA must have been through Presidency College. What about the school? Though the feeder school to Sanskrit College is possible, given proficiency and expertise in English, I think it boils down to Hare School (established in 1818), Hindu School (established in 1817) and Oriental Seminary (established 1829).

Among the Bengali bhadralok, because of Henry Louis Vivian Derozio and the Young Bengal movement a few decades earlier, Hindu School had become less favoured. Oriental Seminary was famous for the quality of its education in English. The noted Shakespearean scholar, Captain DL Richardson, taught there. Though Rabindranath Tagore dropped out of any system of formal education, he did study for a while in Oriental Seminary. Had Manmatha Nath Dutt studied in Oriental Seminary, Rabindranath Tagore would have known him personally, as a co-pupil. Forced to choose a school, I would opt for either Oriental Seminary or Hare School.

(This is the fourth part of an essay on Manmatha Nath Dutt by Bibek Debroy)

Other Related Articles