Welfare Without Populism

The Modi government resists economic appeasement even as Opposition-ruled states revel in it

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

PR Ramesh

Siddharth Singh

|

01 Sep, 2023

Siddharth Singh

|

01 Sep, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Welfare1.jpg)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi launches Ujjwala 2.0 at Mahoba in Uttar Pradesh, August 10, 2021 (Photo: PIB)

ON AUGUST 19, KARNATAKA CHIEF MINISTER SIDDARAMAIAH dashed off a letter to Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman demanding that his state be given ₹11,000 crore as part of the state-specific grants that had been awarded to it by the Fifteenth Finance Commission (FC). The letter went on to state: “…no grants have been released to the state of Karnataka so far. This has dealt a significant blow to the state’s fiscal position, which is already strained due to severe cuts in tax devolution.”

Most of us know the proverbial phrase “Is the glass half-empty or half-full?” used rhetorically to indicate that a particular situation could be a cause for pessimism or optimism. It is used as a litmus test to see how one views the world, either positively or negatively. To those sympathetic to Karnataka’s position, what the chief minister wrote indeed had merit. Karnataka has lost majorly in FC awards due to the income-distance criteria adopted by the commission. This is the so-called ‘federal’ perspective to state finances.

But it is worth probing deeper into what prompted the new chief minister of the state to demand money from the Centre barely one-and-a-half months after the state’s budget was presented in early July. A glance at the budget shows that the state’s net receipts are expected to grow by a healthy 12 per cent in 2023-24. The revenue deficit is also expected to be 0.5 per cent of GSDP in 2023-24, a tad lower than the revised figure for 2022-23. Then what explains the desperate letter?

A closer look at the budget numbers tells a different story. In terms of budgeted sums—and not as a proportion of the state GSDP—the revenue deficit is projected to jump a whopping 109 per cent from 2022-23 and the fiscal deficit by a huge 9 per cent over the same period. And there is an open secret behind these galloping deficits.

In the run-up to the strongly contested state Assembly elections in May this year, Congress bested the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) with hefty ballot numbers. But a core part of the winning party’s manifesto was the “five promises” it made to the state’s voters.

In its analysis of the 2023-24 state budget, PRS Legislative Research said: “The annual cost of these guarantees has been estimated to be ₹52,000 crore. In 2023-24, the state has budgeted to spend ₹39,825 crore (for July-March) for these schemes. The spending on these schemes accounts for 16% of Karnataka’s budgeted revenue expenditure in 2023-24.” These are not one-off expenditures but are recurring, on an annual basis. The ₹52,000 crore figure is for 2023-24 and it is quite possible, if not likely, that these costs will rise in the years ahead. Even for a rich state like Karnataka, they impose a heavy burden on state finances. Such is the nature of economic populism, however, that parties and governments are willing to incur ruinous expenditures for the sake of political expediency.

The same situation, in an equally virulent form, can be seen in another state: Rajasthan. There, the Ashok Gehlot government, which faces a tough election test in a couple of months, has opened the spending taps in the state. Couched in terms of ‘welfare’, most of this spending is a thinly disguised attempt to woo the electorate. Sample this: 100 units of free electricity for all households. Waiving fuel surcharge and other levies on electricity for consumers up to 200 units. LPG cylinders for ₹500 for those in the BPL category. Free scooters for 30,000 girl students and a minimum monthly pension of ₹1,000 under the state’s social security scheme, and more.

These steps may indeed sway emotions temporarily but will lead Rajasthan’s finances down a slippery slope in the long run. The state has one of the fastest growing piles of outstanding liabilities in India and its finances are already under severe strain. In 2023-24, Rajasthan is expected to spend 56 per cent of its estimated revenue receipts on committed expenditure (salaries, pensions and interest payments). But at the moment, in the peak of electoral heat, these considerations and calculations appear superfluous.

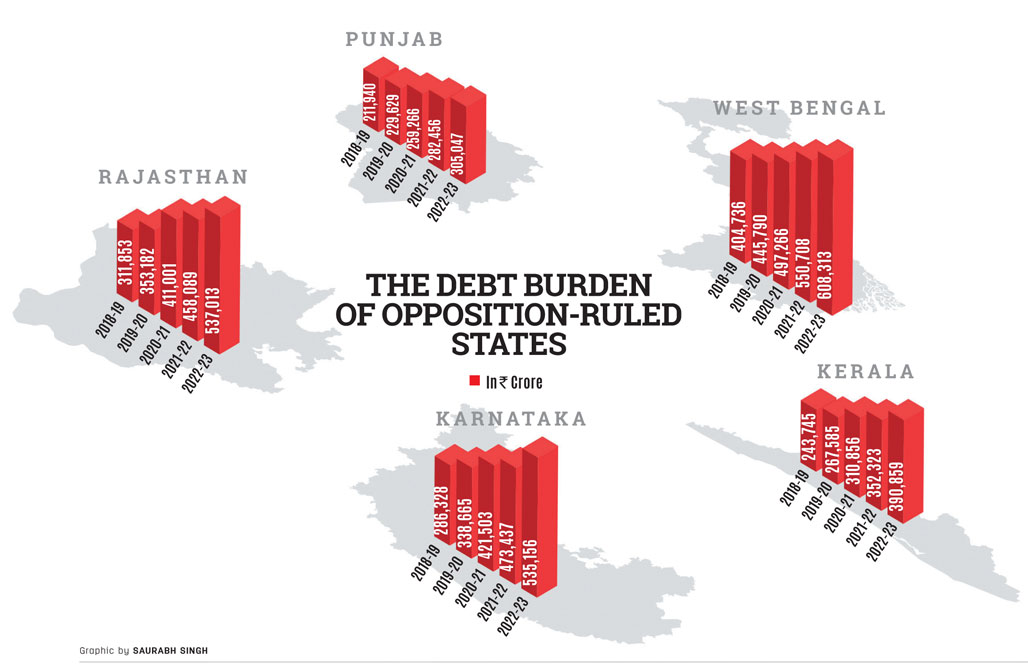

This story repeats itself across Indian states from Punjab to West Bengal and from Delhi to Kerala. In this motley group of states, if there is one that stands as a warning to everyone who wants to play the populist playbook, it has to be Punjab. It is the most indebted state in the country (47.6 per cent of its GSDP in 2022-23). After accounting for committed expenditures (that will eat away 75 per cent of its estimated revenue receipts in 2023-24) and subsidies, there is precious little left for anything. The once-richest state of India is now one of its economically most damaged ones. All because one day in the 1990s, a chief minister had decided to give free electricity to all farmers in the state. Since then, there has been no looking back. Debts have continued to mount even if there is little electricity to distribute, especially in the summer months. It is worth noting that in terms of outstanding liabilities, Rajasthan is just a short step behind Punjab at 40.2 per cent of its GSDP. These are major states and not special category states and given their huge expenditures, their condition is alarming.

In Himachal Pradesh, where BJP was defeated in the Assembly elections late last year, Congress gained on the basis of its promise to restore the Old Pension Scheme (OPS). The new government lost no time and quickly notified OPS without thinking through the financial consequences of the decision. Earlier this year, the state government ran into such difficulties that it could not pay the salaries of its employees on time. With a natural calamity striking the state this monsoon season—the initial estimate of losses is ₹10,000 crore—it will be a herculean economic task for Himachal Pradesh to generate sufficient revenue to meet all these obligations. It is worth noting that Himachal had the highest amount of spending among all states on pensions and retirement benefits as a percentage of its revenue receipts (21 per cent) in 2022- 23. Once OPS kicks in fully one or two years down the line, it is anyone’s guess what the fiscal situation of the state will be. Himachal is a special category state that gets extensive financial help from the Centre.

On paper, there could not be a more diverse set of states than Karnataka, Rajasthan and Punjab. One could be accused of comparing apples, oranges and bananas. But the analogy is misleading. The states are comparable in one way: they are all opposition-ruled states in the grip of economic populism. A comparison between them on purely economic terms makes little sense, no doubt. Karnataka is the richest of the three with a per capita income of ₹3.31 lakh (2022-23) and is also, till date, not in the sort of fiscal mess visible in Punjab. Karnataka’s fiscal condition is not quite as perilous as that of Punjab. Its debt as a percentage of GSDP stands at 23.4 per cent (2022-23), which is less than the national average of states and Union territories (UTs), which stands at 29.5 per cent.

There is, however, one way to view the three states together: they are reflections of each other as economic populism and fiscal sclerosis proceed. Punjab remains the most extreme example. But it is not difficult to imagine Rajasthan joining its ranks if it persists with the populism seen with the Ashok Gehlot government at the helm. Karnataka has begun its journey on that path this year. Even for a rich state, an estimated expenditure of ₹2.5 lakh crore over five years is a tidy pile of money that can be used far more productively than on subsidising public transport and consumption of electricity.

At the moment, matters look ‘normal’. But the reality is very different. Karnataka’s fervent pleas for money from the Union government and the open declaration by its Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar that the government will have to re-order spending priorities tell a different story. The budget was presented on July 7 and on July 26, Shivakumar told reporters: “We will not be able to provide for development this year. We will not be able to provide—in the irrigation department or PWD department, but there is a huge expectation (from MLAs). We have asked them to wait. We will explain the situation to them in the legislature party meeting.”

COMMENTARY ON INDIAN politics often uses the term populism to refer to short-term, electorally driven, politically motivated, and untargeted expenditure. Some of the defining decisions of such populism were taken in the mid-1970s by then-Bihar Chief Minister Jagannath Mishra. Mishra, a political greenhorn, took over as chief minister in Patna in April 1975, just three months after his brother and then Union Railway Minister LN Mishra was killed in a bomb blast in Samastipur, Bihar, on an official visit. Jagannath Mishra was a professor of economics at the Bihar University, Muzaffarpur. His elevation to the post of chief minister came just prior to the imposition of Emergency on June 25, 1975. In a concerted bid to consolidate his position and shore himself up against the blowback from Emergency, Mishra ‘regularised’ teachers in all manner of colleges, private, aided and semi-aided, across the state in 1977. The government used to foot the bill of salaries and wages for these teachers. Overnight, ‘educational institutions’ mushroomed state-wide, marking the beginning, in the dreary Bihar of the 1970s, of a pernicious trend that resulted from politically motivated populism which subsequently spread throughout the country.

Karnataka’s net receipts are expected to grow by 12 per cent in 2023-24. However, a closer look at the budget tells a different story. In terms of budgeted sums, the revenue deficit is projected to jump 109 per cent from 2022-23 and the fiscal deficit by 9 per cent. There is an open secret behind

these galloping deficits

As chief minister, he made another populist decision—that of declaring Urdu the second official language in Bihar, consolidating a coalition of Upper Castes, Muslims and Dalits that kept out an impending uprising of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in a complex state on the threshold of political turmoil. It worked well for Mishra who served as chief minister for three different terms. He came to be known as Bihar’s most powerful chief minister in his next two terms before the advent of Lalu Prasad. But what worked well for him politically created a socio-economic mess for Bihar that lasts even today.

Three decades later, in a state very different from Bihar, a bitter electoral campaign was being waged. Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat, was facing a vitriolic campaign in 2007 from Sonia Gandhi and her allies. Gujarat was preparing for state elections and most media projections put Congress back at the helm in Gandhinagar.

Fired up by that, then Congress president Sonia Gandhi referred to BJP’s chief ministerial candidate as “maut ka saudagar” at Navsari on December 1. If the objective of Congress was to catch Modi with his back to the wall politically, it could not have backfired worse. Leveraging this to his political advantage, Modi, an excellent communicator, turned the tables on Congress, claiming at rally after rally, “I am a son of Gujarat, do I look like a maut ka saudagar to you? You must teach Soniaben a lesson.” Sonia Gandhi’s attempt to highlight the post-Godhra riots and pin the blame on Modi fell flat. Modi swept the polls and returned to power in Gujarat, making Congress eat dust.

But the political field was not the only one in which Modi took on the opposition boldly. In the run-up to the 2007 state elections in Gujarat, Congress had committed to voters that if it formed the government, it would deliver free electricity. A veteran journalist covering the election in the western state told Modi that “emotive issues” were losing their appeal and this round would be fought on “kitchen-table” issues. The next day, at the end of a public meeting, just a handful of journalists remained at the venue. They were asked to recall their colleagues who had left for the day. To this group of reporters, Modi emphatically asserted that the BJP government would not give free electricity, at any cost, to those who consumed it. Every consumer would mandatorily have to pay his electricity bills. “What we can and will ensure, though, is this: every single paying consumer will get quality power and uninterrupted power.” As far back as the early 2000s, Modi was determined that populist politics would not dominate or dictate his government’s economic policies.

Sixteen years down the road from those days in Gujarat, Modi has stuck to his stand against populism and irresponsible ‘welfarism’. The expected turning on of spending taps in the last year before elections in 2024 has not taken place. If anything, Modi has spent the past several years warning the country about the dangers of economic populism and easy resort to a “revdi culture”. In May this year, at a rally in Ajmer, Modi warned against the ill effects of economic populism in the shape of freebies. His message was stark: If a government and a country spent money beyond its means, it would be walking on thin ice. In the context of the promises made by Congress to voters in Karnataka, he emphasised that if these guarantees were implemented in every state, the nation would be bankrupt. He listed for his listeners names of countries on the verge of bankruptcy due to such populist policies.

The same message was repeated at the beginning of last month when the prime minister was in Pune to inaugurate a Metro line. Again, in the context of Karnataka, he said, “Today, the entire country is worried about the freebie culture that has negatively impacted Karnataka. When a party, solely for selfish reasons, empties the state’s treasuries, it impacts the state’s people the most. This impacts the future of our youth.”

One state that stands as a warning to everyone who wants to play the populist playbook is Punjab. It is the most indebted state (47.6 per cent of its GSDP in 2022-23). Rajasthan has one of the fastest growing piles of outstanding liabilities. In 2023-24, the state is expected to spend 56 per cent of its estimated revenue receipts on committed expenditure

He went on to add: “The situation is that the Karnataka government is itself claiming that it has no money for not only Bengaluru but Karnataka’s development. This is very worrying for the country. The same situation is being repeated in Rajasthan. Here too, there is an increasing debt burden and development projects have come to a halt.”

These examples can be multiplied. But the messaging has been consistent through the Modi era, both during his time as chief minister of Gujarat and since he became prime minister in 2014. The idea is simple: Yes to targeted welfare, a big No to freebies.

It is a cliché that economic populism is destructive to the economic health of a country, especially a developing one. The truth of the assertion is abundantly clear but it is often wholly disregarded in the pursuit of political power. The idea was simple: political parties and leaders should generate enough money to spend their way through elections and recoup this during their term in power so as to contest for another term five years down the line. Freebies, allurements in the shape of cash or kind, all were par for the course when it came to tempting voters or staying power.

For the longest time, this practice had traction. The reasoning was pretty basic, too: given the widespread poverty in India, people would want relief from their misery. This, even if it were temporary and bore no relationship whatsoever to finding long-term and systemic solutions for the severe lack of essential goods and services for the most eligible, such as potable water, low-cost housing, affordable food, education and health care, LPG cylinders for cooking, accessible and cheaper public transport, no-frills bank accounts, and more. This worked well for the political class on two key fronts: one, little or no money was left to provide essential goods and services on a large scale to citizens after money had been frittered away on loan waivers and other populist schemes. Two, and more fundamentally, alleviating poverty was contrary to the very grain of the Indian political system: if people were empowered to stand on their feet, there would be no need for welfare schemes. In turn, that would disallow political parties and leaders from tempting voters with pre-poll largesse with overwhelming power stakes and the consequent competition.

The evisceration of the nation, as a result of irresponsible and untargeted welfarism, is not restricted to its economics alone; it dangerously erodes the very core of the democratic processes. Analysts have time and again emphasised that if the integrity of the electoral process is compromised, the very notion of representation becomes vacuous. Although populism has characterised the politics of Tamil Nadu since the 1960s, they maintain, it is since the significant changes ushered in from the 1990s that the terms of populism in politics have also been transformed, seeing this as an opportunity. In his article, ‘To Take or Not to Take: Is the freebie culture in Tamil Nadu a threat to democracy?’ (2021), Sudarsan Padmanabhan raises key questions as to whether the people of India, and especially states like Tamil Nadu, are really concerned about governance or if they cynically participate in the hollowing out of democratic, electoral and political processes. He writes: “In states such as Tamil Nadu in Southern India, distribution of money and promise of freebies has reached alarming levels with elections being countermanded several times. In this scenario, the danger to the system of parliamentary democracy and the Indian republic cannot be gainsaid.”

HOW DID MODI cut through this knot? In a word: honesty. Honesty of purpose, in both politics and economic policy. This is evident in his handling of development as well as managing issues like the availability of LPG. Since 2014, technology has been harnessed in multiple ways to cut through the thicket of intermediaries who rendered any welfare scheme futile even as the political purpose of undertaking such schemes was fulfilled. The money saved from plugging such massive leakages—immense by any budgetary estimate—has been used for multiple purposes, ranging from finely targeted schemes to eligible beneficiaries to the rapid development of infrastructure.

Since 2014, the Modi government has weeded out 1.86 crore fake farmers, 2.5 lakh fake companies, 4.2 crore fake ration cards, two crore fake MGNREGA cards, 4.11 crore fake LPG connections and 28 lakh fake madrassah students. The savings: a cumulative sum of ₹2.73 lakh crore. This has resulted in an unprecedented spending boom on infrastructure. Till 2015, India spent barely 0.3 per cent of its GDP on capital expenditure on roads and railways. Since that year, this figure has been rising steadily without a break. In 2023-24, the spending is expected to touch a massive 1.7 per cent of GDP on road and railway infrastructure.

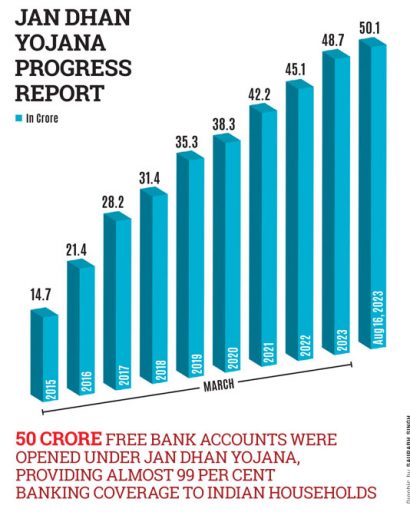

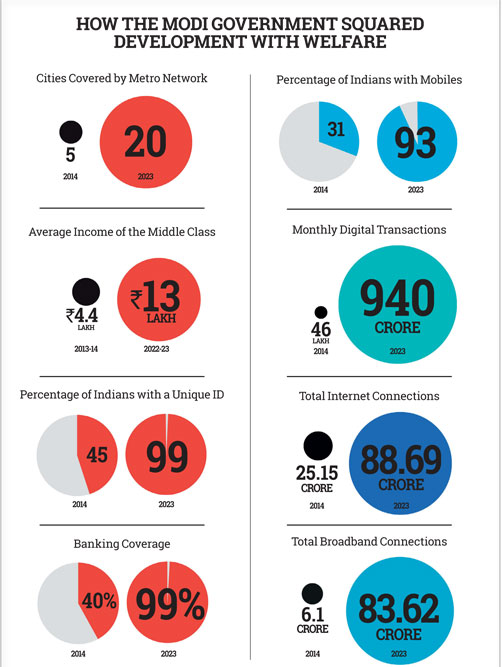

Another part of the ongoing transformation of the Indian economy is its emphasis on digital public infrastructure. This is visible in a series of metrics observable from 2014. In 2014, the percentage of the population having mobile phones was 31 per cent. By 2023, it had shot up to 93 per cent. Similarly, the percentage of the population having a unique identity in 2014 was 45 per cent. This had increased to 99 per cent by 2023. This had an immense impact on digital transactions that require identities for purposes of safe and smooth processing. In 2014, monthly digital transactions were a measly 45 lakh. In 2023, these numbered 940 crore. This has had an impact on banking coverage also which has gone up from 40 per cent in 2014 to 99 per cent in 2023.

Then there are issues like enabling people to avail facilities like LPG for cooking and the availability of this good at reasonable prices. In the 2012-14 period, the annual LPG subsidy burden on the government was very high at ₹46,000 crore. This subsidy expenditure was financed through borrowings at 9.5 per cent interest. Over 10 years, total interest paid would have been ₹43,700 crore. Only six to nine subsidised cylinders were allowed per household annually and there were long waiting times of four-seven weeks for the delivery of cylinders, with non-subsidised cylinders costing anywhere from ₹1,250 to ₹1,400, making them unaffordable for most people.

The Ujjwala scheme gave 10.35 crore connections to BPL households with the number of LPG connections now touching 32.5 crore, up from 14.52 crore in 2014. Twelve subsidised cylinders are now allowed per household annually even as there is no waiting time for cylinder delivery. Two days ago, the price of subsidised cylinders was reduced by ₹200, and those under the Ujjwala Yojana now enjoy a subsidy of ₹400. Non-subsidised cylinders are now priced in an affordable ₹900-1,000 range. The use of direct benefit transfer (DBT) to plug leakage has improved the targeting of subsidies and the annual subsidy burden has been controlled at ₹7,700 crore as of 2023.

One way to look at the change engineered by Narendra Modi is to claim a repurposing of spending. That is true. But fundamentally, it is about being responsible for the nation’s kitty and honesty in spending, making for integrity both in economics and, consequently, in politics and the democratic process. As 2024 approaches, the drumbeat of populism will also rise in volume and tempo. But unlike in the past when there was only one choice—populism and more populism—this time there is an option: populism as against honesty of purpose and reinforcement of democracy.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

India holds the upper hand as end of hostilities with Pakistan announced Open

Ajay Kumar Garg Engineering College (AKGEC), Ghaziabad Open Avenues

Sanskriti University Open Avenues