Meat Is the New Black

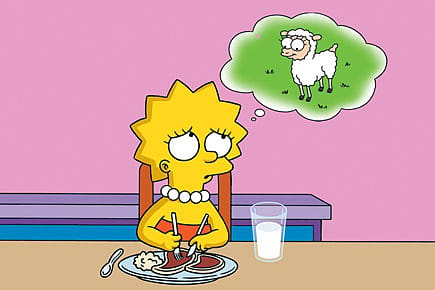

The newfound meat fetishism of well-heeled Indians reflects their desire to be seen as jetsetting bon vivants with a discriminating palate.

The newfound meat fetishism of well-heeled Indians reflects their desire to be seen as jetsetting bon vivants with a discriminating palate.

"We've ordered Thai," says my host, sheepishly under his breath, "I think there may be some veggie stuff in there." I discreetly exit before the food is served, heading off a culinary crisis, to the other dinner on my evening's itinerary. "I can't believe you don't eat meat," squeals Manisha in equal parts dismay and disbelief soon after I walk through the door. "Now you're eating leftovers!" she protests, as her cook serves me delicious aloo parathas, and the rest of her guests tuck into their carnivore-friendly feast.

Over the past twenty years in the United States, I have survived congealed dorm food, plates upon plates of grilled vegetables, a stroke-inducing diet of pizza, fries and pasta, and finally, ten blissful years in that vegetarian mecca, San Francisco. All this to return to a new and improved India, where I have once again joined the ranks of the gastronomically challenged; a "special needs" person with a dietary disability, i.e., my aversion to animal flesh. As with the disabled, I am obliged to signal my presence in advance if I am to be entertained. "You better let me know if you are coming," warns an acquaintance on inviting me to a book party at her place. "I'll be making a vegetarian curry just for you because everyone else eats meat."

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

India maybe home to the greatest number of vegetarians—300-odd million at last count—but its wealthier citizens are voraciously carnivorous in aspiration, and increasingly so in their diet. In the land of Gandhi, meat is a basic food group in the yuppie meal plan—bacon for breakfast, burgers for lunch, kebabs for dinner. Meat is the new black.

Back in the dark days of pre-liberalisation, Punjabi friends I grew up with in Delhi ate meat with regularity and relish, as in two to three times a week at home and each time they ate out. My disdain for the stuff was at worst a 'Madrasi' affectation that they did their cheerful best to cure: "Just taste the mutton pickle. Promise you'll love it." My culinary naysaying was deemed incorrigible, but there was always plenty for me to eat at any table I was invited to join.

"Samira, you should have told me she was vegetarian," grumbled Mrs D, the matriarch of my dorm-mate's host-family, on a damp New England afternoon in 1987. Within minutes of walking through the door at my first American home-cooked meal, I'd driven my hostess right back into her kitchen in a frantic effort to drum up something other than a side of boiled peas. It was the first inkling that my dietary restrictions were not merely different, but also onerous on those tasked with feeding me. Two decades later and I am right back where I started: a mortified fresh-off-the-boat emigre caught in a gastronomical faux pas at a meal hosted by the natives. "It's deja vu all over again," as the patron saint of non sequiturs, Yogi Berra, would say.

In aspiring India, we lowly vegetarians have fallen from grace and right off the map, and are now entirely invisible to food section editors in upmarket publications. Restaurant reviews, for instance, rarely mention vegetarian items on the menu (except when unavoidable as with cheap eats like bhelpuri, dosas or chaat). Gourmet cuisine is clearly not for us shakahari chumps. Titled 'How to be a Culinary Show-off', a weekend cover story in Mint lists the following "envy-inducing table": Khow Suey (with chicken and eggs), Naga-style pork, chicken tea soup, wintry sausage and mustard pasta, chicken stew, mustard fish and—trumpets please!—aubergine in a garlic-yogurt sauce.

Vegetables are déclassé, as are vegetarians. We are far too low-rent to accommodate either on the menu or at the table—even our own. Invited to a vegetarian friend's birthday celebration, a young IT executive grouses, "But there won't be anything to eat." Others may call in advance merely to uphold the rules of good hospitality: "You are serving a couple of non-veg dishes, right?" A self-deprived hostess is hardly good reason for her guests to do without, be it for an occasional meal.

Of the various meats, beef is the ultimate standard-bearer of cool, a cultural signifier that denotes membership in a cosmopolitan India whose taste for the once-forbidden meat marks its distance from the old. What was once low caste is now high class, served up in trendy restaurants with nary a chicken tikka in sight. With the exception of five-star hotels, most upscale dining in Bangalore is studiedly not-Indian. At least part of this newfound meat fetishism reflects our desire to be seen as jetsetting bon vivants with a discriminating palate. On my first night out in Bangalore, an immaculately hip woman at our table fussed for half an hour to triumphantly settle on beef stroganoff—the entree of choice in frozen TV dinners across blue-collar America.

Among the UMARs (upper middle and rich Indians), meat-eating has become a competitive sport. Armed with their uber-expensive Weber grills, the elite routinely stage barbecue cook-offs, their tables groaning under the weight of dead creatures imported from corners of the world: New Zealand lamb, Canadian bacon, Angus beef, Niman Ranch burgers, Norwegian salmon, anything that breathes is grist to the almighty grill.

In her book, Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Elizabeth Collingham describes the colonial tradition of the Burra Khana. East India merchants loaded their tables with turkeys "you could not see over—round of Beef, boiled roast Beef, loin of Veal for a side dish and roast big capons." And that was just the first course, to be soon followed by a second course of beefsteaks, pigeon pies, chicken drumsticks and quails. "It was on their dinner tables the British in India most extravagantly displayed their wealth and status," driven by their middle class determination to imitate the English aristocrat. In rushing headlong toward the future—our lavish, epicurean tastes apiece with our global swagger—we have followed dutifully in the steps of our past masters, fully embracing meat as the sign of cultural virility and power.

"Is the baby eating chicken yet?" demands my Jat husband over the phone from San Francisco, suspecting a conspiracy to corrupt his child with my TamBram squeamishness. "You are not raising her vegetarian, are you?" asks a friend, as I skip past the cured meats at the local gourmet bazaar, with my eighteen-month old in tow. God forbid, I should deprive my child of a bright future as a well-adjusted carnivore. "No," I want to say, "I'm raising her to eat well-fed meat-lovers like you." They say human flesh tastes a lot like chicken. Yum!