For the Day Bihar Thinks Beyond Caste

"I am going to Patna, Bihar."

"Why?"

"It's election time."

"Again…didn't you guys just have elections… How many times do you people vote, jeez!"

This was just another conversation with my best friend in Montreal. She just can't seem to get her head around the fact that I am going to cover another election. Last time I talked election and voting was hardly a few months back, during the Delhi polls. Fast-forward six months, and the elections are here again. This time, we are talking Bihar.

Ever since the dates were announced, people from Delhi have been crowding Bihar; 16 choppers and more have been stationed at Patna's Jayaprakash Narayan International Airport. Leaders and 'star campaigners' of all major parties, be it of the BJP or of the JD-U-RJD- Congress 'Grand Alliance', are descending upon the airport as early as 6 am to take on the heat, literally. The six daily flights to and from Delhi are flying packed. Two 'five star' hotels in Patna are experiencing one of their busiest seasons. The election carnival is in full swing in this state. Those thronging Bihar, besides the politicians, can also be divided into different 'castes', if I may. There is the 'secular' media. There is the English 'secular' media. There are senior 'forward' journalists. There are (non)-partisan journalists. And then there are the novice journalists. Everyone has been decoding and trying to decode the Bihar election. Some are giving a hands-down victory to the BJP-led NDA. Some are calling it in favour of the 'Maha Gathbandan' or Grand Alliance. A few are giving an edge to the BJP on its own. And others are saying it's 'too close to call'.

As for the newbie, Bihar electioneering is an eye opener.

"So, what is different about Bihar elections then?"

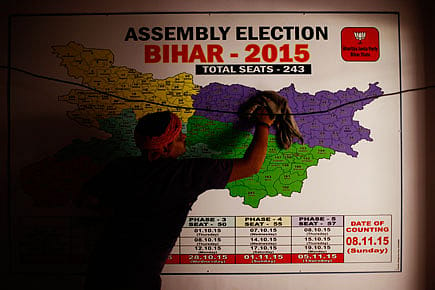

"Everything is different. Bihar is huge, with 243 constituencies and more importantly the state is still very caste-ic"

"Caste-ic?"

"The state works and behaves along caste lines."

"Jeez… We have enough divisions without dividing ourselves up even more."

Sigh

In India, there is no better place to talk about the complexity of politics than in Bihar. The matrix is intricate and unwieldy. It is a model example of the sheer number of divisions that we Hindus have created among ourselves.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Having covered and understood the previous few polls in relatively simple states, working on Bihar requires first figuring out all the castes that exist. However, the state started making sense once I began to visit constituencies. The underdevelopment of Bihar also started to make sense. Why Bihar continues to be one of India's so-called BIMARU states also began to make sense. Bihar is caustically 'caste-ic', as I call it. It is a mesh of so many jaatis that the mind boggles and wobbles. Its backwardness explains itself. And it's sad that at a time when the Government at the Centre has chosen to defy caste politics, at a time when it almost seemed that Mandal politics was over, Bihar came up and proved such assumptions all wrong.

Campaigns here are run on caste, which makes the election interesting but complicated and very confusing. Prime Minister Modi, who is devoting more than his usual sweat and toil to these elections, is fighting for 'parivartan' or change. But Biharis are being wooed on caste. A Modi Sarkar leader unabashedly proclaimed that the Bihar election's outcome will be based "20 per cent on Modi and 80 per cent on caste".

Once you leave the city of political billboards, aka Patna, and travel around the villages of Bihar, the percentage makes sense. While making our way to Modi's rally at Nawada, we took pit stops at many villages. Each village had its castes and clans to whom special appeals were made.

Musahars have been in the limelight because of the prominence in the NDA of Jitan Ram Manjhi, a leader of this group and former Chief Minister who has been very vocal in this election. Manjhi has his own party, the Hindustani Awam Morcha, and is a star campaigner of the NDA.

Of any caste or creed, Biharis are very politically aware, conscious of their interests and with each a kind of political pundit on his own. From a server at a hotel to a taxi driver or farmer, even children can speak knowingly about the politics around them. The state may lag in literacy, but when it comes to politics, they beat even seasoned journalists and analysts. Everyone knows his or her local MLA, their parties and their 'work'—which for most is the work done for their own caste group.

In the village of Musahars, one person stood out: a young girl, a first time voter. Having just come back from school, she still had her uniform on. When asked who she would vote for, she gave a sheepish smile and said, "I want to vote for Nitish Kumar, because he has worked for us, he has given us cycles to ride to school. He has given us good roads. He has worked for us…." However, after a brief pause, she added, "but… I will vote where my village votes." By that, she meant Manjhi.

The same is the case with Yadavs, Dalits and Mahadalits or Bhumihars, Rajputs and their ilk. They all know whom they want to vote for, each sticking to caste or clan loyalties. No one is weighing their leaders or options by the yardstick of promises or visions of development or progress. Though everyone sounds happy with the work done by Nitish Kumar, there are few who say they will vote on merit.

Clearly, in Bihar, people do not cast votes so much as vote castes.

But amid these vocal communities, stands the meek and timid group of Extremely Backward Classes. Apparently, there are 130 odd castes in this category. And it is these voters who could be the game-changers of this election. They are the silent voters. The ones who will be pressured and threatened by domineering Yadavs and Bhumihars to vote for their choice. After witnessing the fanfare at the Modi rally, on our way back to Patna, we stopped to talk to some Barhais (carpenters). None was willing to speak or express a political view. Only after much probing did they speak, but the words were carefully weighed. Just like the Musahar girl, a young man spoke in whisper, "We will vote for Nitish Kumar…" But before he could continue further, a Bhumihar interjected, claiming the group present would vote for the BJP. There is a couplet you hear in Gaya, Bina jhaad ka pahad, bina paani ke naadi, aur bina buddhi ke log. Translated in English, it says, 'A mountain without trees, a river without water, and people without brains'.

The kind of debates needed are not to be heard in Bihar. Yes, its voters are very politically aware, but caste dominates the voice of many even as a vast majority want to remain mum. For the past 25 years or more, Biharis have elected state governments on the basis of caste. And this looks likely to go on.

But there is hope. After all, isn't India also riding high on 'hope'?