Lust for Life

AMONG THE PREFATORY pieces in Arunava Sinha's translation of Manoranjan Byapari's There's Gunpowder in the Air is an excerpt of a profile on the author from the journal Review/Preview. Here, Byapari generously decries his disenfranchisement and alienation. He employs a rhetoric that recreates not only the melody of his famed oration but also the oft-censored bane of his coerced dissociation. 'To a high caste person I'm a dalit, untouchable,' he claims. 'To other dalits I'm a rickshaw-driver. To other rickshaw-drivers I'm a writer, and therefore untouchable as far as they are concerned.'

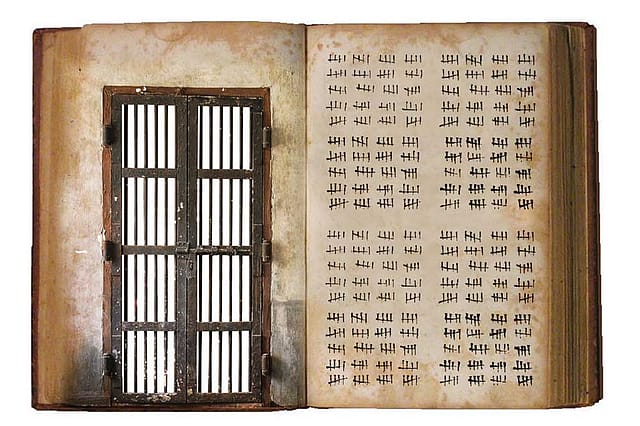

In Byapari's novel, Bhagoban, convicted of petty thievery, is assigned by the jailor, Bireshwar Mukherjee, to infiltrate the intimate group of five Naxal men conspiring to flee from prison in lieu of minor favours like ration and other basic amenities— currencies of power for the incarcerated and their keepers. However, on the very first night of Bhagoban's assignment, an act of kindness from Bijon, the man next to his cell who passes a portion of his ruti-torkari (rotis and vegetable) to his famished neighbour, endears him to Bhagoban. Riled up by the confusion of allegiances, he becomes an in-betweener. And, in so doing, inhabits the status Byapari so deftly articulates.

In a testimony relayed to Meenakshi Mukherjee, subsequently titled 'Is There Dalit Writing in Bangla?', Byapari charts the history of Bengali Dalit writing which began two decades after the corpus of Dalit literature gained momentum in Maharashtra. He evokes the dispersed lives of the Dalit community in Bengal. He refers to the ejection of Namashudras from Khulna, Faridpur, Jessore and Barisal in East Bengal following the 1947 Partition. He cites the atrocities meted out to Dalit settlers on the island of Marichjhapi in the Sundarbans. With continual attacks on a stable and communal Dalit existence, 'creative activities like writing were affordable luxuries'.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

But it is only through the written word that Byapari has appealed for jijiisha, which in English loosely translates to 'a lust for life'. This unaffordable luxury was adapted into a tool of necessity. Literacy was not a means to assimilate but to upend cultural, political and economic hegemonies. In reading Byapari's novel, one is not only struck by the first- hand perspective of Bengal's prison systems but also by its style of prose: bereft of aesthetic aspirations, melodrama and a humour which is always imposingly dark (Haloom, the obese white cat, is mistaken for the ghost of a former prisoner who succumbed to first-degree burns administered by his partner in crime in a live-and-let-die move).

His style may be difficult for the reader who has been reared on the standards of aestheticism established by Indian writers who write about Dalits from a distance or do not write about them at all. It is, in Byapari's own words, 'direct, blunt and explosive—devoid of stylistic elegance'. Here, Byapari may be making a case not only for himself as an idiosyncratic Dalit aesthete but also for distinct Dalit livelihoods that are attempting to resist subsumption.

The jacket of Byapari's novel describes Sinha's translation as 'deft'. I believe that his translation is merely dutiful. Sinha is respectful of Byapari's stylistic tendencies. He neither tampers with the cadence nor betrays an aspiration to superimpose an 'elegance' distinct from Byapari's. With pique I must add that certain dialogues are transliterated from the Bengali source text in English and an immediate English translation added. Here, on the one hand Sinha preserves the linguistic identifiers by means of which socio-economic and even geopolitical identities of certain characters can be easily determined. Yet, on the other, the English that follows immediately erases and renders unnecessary Sinha's reproductions. Only a Bangla speaker acquainted with the myriad dialects is welcome in this in-between space between author and translator. Yet, the translation and, above all, Byapari's fiction convey the addition of an invigorating literary voice to the canon not just of Bengali Dalit writing but of Indian literature.