A Wounded Memory

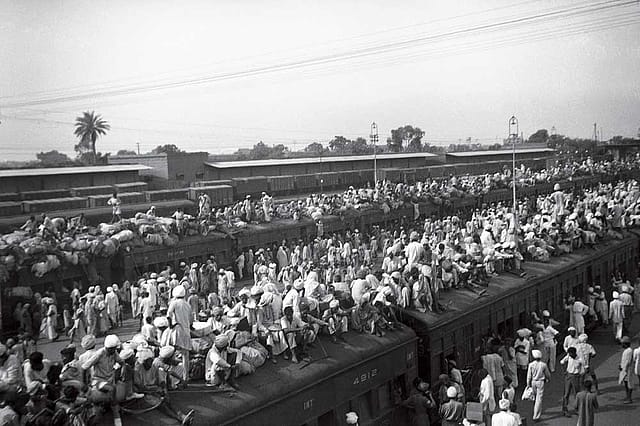

"IT'S NOT THAT he has forgotten… it's just that he can no longer remember," Bharati Sanyal says about her husband's recollection of life in what is now Bangladesh. The Sanyals are one of the many interviewees in Aanchal Malhotra's Remnants of a Separation who struggle between varying degrees of remembering and emotional amnesia to recount their experiences of Partition. Bharati's insistence that forgetting is not the same as no longer remembering might be true of how we all construct Partition histories, whether we lived the event or not. Seventy years after a cartographic rip that tore apart lives and communities— perhaps those of our parents and grandparents and, in inheritance, even our own—we do not always remember Partition, though we never truly forget it. The word slips off our tongues in living room conversations as if it were the name of an epic we all know. We assume we all know how it went. And we rarely enunciate its weight.

Malhotra's book addresses this omission, and attempts to 'unravel the word' through different people's memories. In doing so, the book wants to return to our utterances of 'Partition' a weight it is losing. Partition by Barney White-Spunner shares a similar aim, though its methods differ significantly. White-Spunner, a British soldier who served in Iraq, investigates through political, military and personal records the year leading up to Indian independence and the formation of Pakistan in 1947. His is a more traditional telling of wars and failed political agreements, while Malhotra attempts a 'history from below'; this distinction, however, does not imply that either approach is better than the other.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

Malhotra gives us a sense of the continuing heaviness of Partition through material objects, things we can touch and hold, preserve and misplace, even destroy. Beginning with her own grandfather, Malhotra interviews people of different backgrounds who experienced Partition and asks them to show her their prized possessions that have survived. These objects trigger memories of wider happenings of Partition and life before it. Soon, it is no longer about a box, or a shawl, or a string of pearls, but of the pasts those objects have lived and lived within.

By prodding recollections through assorted objects—from graduation certificates to kitchenware to pieces of silk— Malhotra unearths narratives that are often tactile rather than pointed enough to fit a timeline. Hansla Chowdhary still drapes her grandmother's bagh—a large fabric covering, embroidered collectively by the women of her family—as a wearable archive to remember old feelings, customs and legacies. "Wearing it means keeping it close to my body," she says, "it feels as if I am living in history." This kind of 'malleable memory', Malhotra suggests, 'takes years to ferment' and rests 'between fact and fiction', tracing a genealogy of a past that hasn't fully resolved.

One success of Malhotra's research is that it never exits conversation. She, as the interviewer, is always present, asking her subjects to repeat themselves when she doesn't understand them, or allowing them and herself to depart on tangents as one does in everyday chit- chat. Often, she treads dangerously close to being too present, almost interrupting the gravity of another's story with her own processing of it; thankfully, she steps back in time. The conversations switch languages as needed, between English, Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi and other dialects, for so often we just need to find the right words to recall the past—Sindhi, we learn, has no word for 'partition'. "Language is bound to soil," Shobha Mirchandani, a Sindhi, says, "and we no longer have any soil of our own." As these voices and accents quiver, then become firmer as they excavate events they have lived, Malhotra shows us that Partition carries with it lost lives, but also lost vocabularies that could perhaps describe those lives more fully.

In finding ways to account for these losses, to put together the word 'Partition', Malhotra doesn't go back in time, but back and forth across decades and across the border, interviewing people from all three sides whose objects arrived at different times, sometimes retrieved even after Partition. Malhotra allows a history to emerge beyond its tellers. We learn of political strife, present-day Indo- Pak relations, and contested definitions of 'nation'. Unlike Malhotra, White- Spunner attempts a more direct investigation, back into the past in one direction and along a more defined border. He finds the lost words Malhotra points to in documents that have survived beyond the Raj, and writes of Partition largely as it emerges from official archives.

White-Spunner's Partition makes two major points. First, the British stayed too long in India. Although the British transferred power to India a year earlier than expected, White-Spunner argues they should have granted India Dominion status after World War I, as they had done with South Africa and Canada. By denying self-government when it was demanded, the British agitated political forces within India and steadily weakened the Raj. Communal rifts also increased and perhaps Partition, or at least how it unfolded, would have followed a different trajectory had the British left earlier. Second, White-Spunner argues that the bloodshed that accompanied Partition could have been mitigated had the army been deployed effectively.

The most compelling arguments in Partition are about the army. After the World Wars, relations between British and Indian soldiers, and among Indian soldiers of different castes and creeds, changed. There was more equality among soldiers but the army was also increasingly ignored, which meant that those in charge of the political handover didn't have a strong vision for this more egalitarian army's future. Communal friction entered the ranks of Indian soldiers, which was exacerbated by the decision to divide by religion the Indian soldiers of the British army between the to-be states of India and Pakistan. So when the handover occurred, and police forces in Punjab went rogue, the reluctance to use what was left of a loyal army (largely British soldiers and Indian soldiers of 'non-partisan' castes) allowed the violence to go unchecked.

White-Spunner reminds us, as does Malhotra, that Partition affected British lives, too—for many, India was home. But in his attempt to write an empathetic account, White-Spunner often gets buried under his own research. There are too many digressions into personal narrations of Partition violence and backstories of characters like Mountbatten, Auchinleck and Nehru. What could have been a focused, insightful analysis of the army's role during Partition gets lost in a book that holds a wealth of facts with no clear vision for their assembly.

Different as they are, White-Spunner's and Malhotra's books demonstrate that 'Partition' quickly frays into many strands when unpacked. Where official agreements, telegrams, and speeches fail, intangibles emerge—memories of possessing physical stuff, memories always at the edge of a more public history. But memories are what we retain and also what we forget. Many of Malhotra's interviewees ask to be pardoned for not wanting to remember the horrific sights of Partition. "Forgetting is important," says Bharati Sanyal, otherwise "our hearts would be too heavy." So maybe it is those forgotten bits, buried in divided soil of similar colour, that carry the true weight of 'Partition'. The weight that must be filled into the Partition history we write to remember. The weight of being so close to what happened, and of still not being sure what did.