Band of Beleaguered Brothers

The struggle for a united opposition to the resurgent BJP falls apart in the absence of a leader or a slogan

Kumar Anshuman

Kumar Anshuman

Kumar Anshuman

|

19 Apr, 2017

Kumar Anshuman

|

19 Apr, 2017

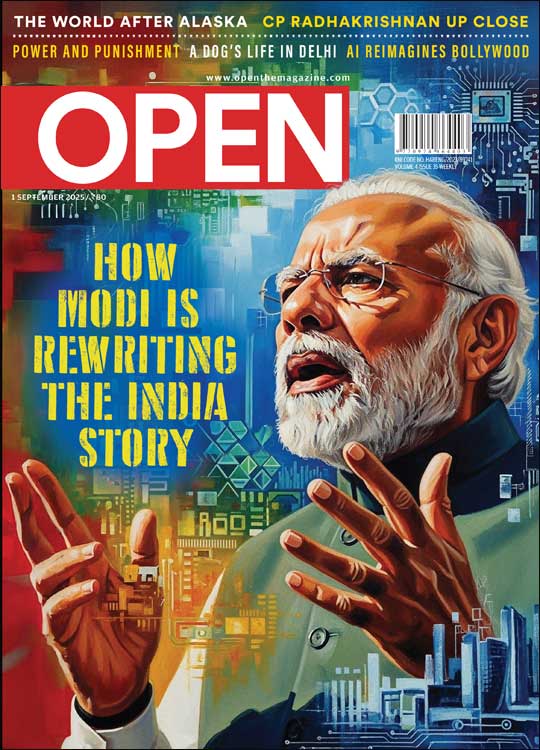

/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Modiopposition1.jpg)

ON APRIL 5TH, SITARAM Yechuri took a long walk to the Congress parliamentary party office, a journey he had not made since the CPM withdrew support from the UPA Government in 2008. He was there on the special invitation of Congress Vice-President Rahul Gandhi. The two leaders met for a good 45 minutes over coffee and sandwiches and discussed various issues, starting with the GST Bill that was going to come up in the Rajya Sabha, followed by the possibility of a coalition before the Panchayat and Nagar Nigam polls in West Bengal. Yechuri’s Rajya Sabha term is coming to an end this August and if his party nominates him again, he will have to rely on votes from the Congress to sail through. But more than anything else, this was a meeting to discuss strategy for the 2019 General Election. A day later, Rahul Gandhi met CPI leader D Raja. “We discussed the current political situation and how to fight communal, fascist threats. We tried to understand each other’s assessment of the situation during the informal talk,” Raja said.

The opposition camp has clumped together after the Assembly elections in five states in March, and especially in the light of the results in Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP won more than a two-third majority. The Modi juggernaut, which started rolling in 2014, has engulfed much of India, barring Delhi and Bihar. Opposition parties now fear complete decimation and there are whispers of a grand alliance like never before. Where anti-Congressism was the cornerstone of erstwhile national alliances, in the current scenario the Congress has ceded centrespace to the BJP.

Just before elections were announced in Uttar Pradesh, BSP supremo Mayawati had completely ruled out any coalition with the Samajwadi Party and Congress. Now that the party has been reduced to 19 seats, she is quick to accept the ground reality. On April 14th, she announced in Lucknow: “I am ready to join any alliance to defeat the BJP. Zehar ko zehar se maarenge (We will kill poison with poison).”

To understand how desperate the anti-BJP parties are, one need only track the inter-party activities that have taken place this month. On April 3rd, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar urged the Congress and Left parties to take the lead in forging a grand alliance against the BJP. The following day, RJD President Lalu Prasad called several regional party heads including Sharad Pawar, Navin Patnaik, Mamata Banerjee and some Left Front leaders to initiate talk of an alliance. On April 5th and 6th, Rahul Gandhi met Yechuri and D Raja. On April 10th, Mamata Banerjee met Samajwadi Party President Akhilesh Yadav in Delhi. She tried to arrange a meeting with Sonia Gandhi but couldn’t get an appointment. But the two later managed to talk for half an hour over the phone. On April 14th, Mayawati spoke out in favour of an alliance. On April 16th, Akhilesh Yadav vowed to play a crucial role in the alliance against the BJP. On April 19th, Mamata Banerjee went to Odisha and met Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik.

A grand alliance makes mathematical sense. The Bihar formula, after all, did manage to stop the BJP in its stride in the state elections in 2015. Even in the UP elections where the BJP emerged the clear victor, the combined vote share of the SP, Congress and the BSP was over 50 per cent, as against the BJP’s 39 per cent. But simple arithmetic doesn’t always work in politics. “Indian voters are moving beyond caste considerations and governance has become a major factor for voting,” says AK Verma, head of the Department of Political Science at Christ Church College, Kanpur. “I think the people of the country are quite upbeat about Modi and they are refusing to be part of negative politics.”

On several occasions in the past, the opposition did come together. In 1977, the opposition united under the Janata Party to beat Indira Gandhi, who was facing popular ire over her government’s excesses during the Emergency. People were ready to support any coalition that could beat her and so the alliance emerged victorious. Another such moment came in 1989. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was facing a credibility crisis after the Bofors scandal and some of his own lieutenants such as VP Singh and Arun Nehru led the opposition against him. In 1996, the opposition once again united against the Congress and the BJP. The Congress under Narasimha Rao was in decline post the demolition of the Babri mosque and the BJP’s star was rising. The alliance did well in the elections and even formed the Government with Congress support. This was the first time the BJP, even though it was not in power, was perceived as a threat by all other parties, including the Congress. The situation now is much more dire for the Congress. Prime Minister Modi is extremely popular among the masses and he is adding victories to his cap with every year. During his term so far, the BJP has won eight states—in four of which the party formed the government for the first time—besides the coalition government with the PDP in Jammu & Kashmir.

In the past, the Left Front performed the role of bringing anti-BJP parties together with CPM leader Harkishan Singh Surjeet playing the ultimate dealmaker

FOR A GRAND ALLIANCE TO work, one of the prerequisites is a leader or a party that can bring everyone together. In the past, the Left Front, especially the CPM, performed this role, with its senior leader Harkishan Singh Surjeet playing dealmaker. In 1996, when the 13-day-old BJP Government collapsed, Surjeet was quick to initiate a discussion with other parties. He was the force behind the formation of the United Front Government. A year later, the then Congress President Sitaram Kesri withdrew support and staked his claim to form the government. But Surjeet, who had been in constant touch with the regional parties that were part of the United Front Government, left no room for defection. Kesri was finally forced to stand down and to once again extend support to the UF. “The CPM wielded power from its strength in West Bengal. Now that it has been routed in Bengal, it is no more in a position to play dealmaker,” says Prasenjit Bose, a former CPM member and a political economist. “If they are at the mercy of others for a Rajya Sabha seat, who would listen to them?”

Rahul Gandhi wants Nationalist Congress Party chief Sharad Pawar, who has friends in all parties, to be the matchmaker. On March 10th, a day before the results of the Assembly elections in the five states were announced, Gandhi had a detailed meeting with Pawar in Delhi. Pawar could well help ease talks between party leaders, but it won’t be long before the proposed alliance hits a deadend. Who will be the face of the front? The Congress is without a strong leader, and despite being the biggest party in the proposed alliance, it has nothing to offer. “Being a bigger party, it is the Congress’ responsibility to take the initiative of bringing all major non-BJP parties onto one platform,” Nitish Kumar said. But his party has already announced him as the alliance leader. Says party spokesperson Neeraj Kumar, ‘In the given situation, Nitish Kumar is the most competent and credible face to lead an anti-BJP front.”

Nitish Kumar’s is a name that is eliciting support from some regional parties. “We are ready to back anyone the alliance leaders choose,” says SP’s Akhilesh Yadav. RJD’s Lalu Prasad, Nitish’s partner in the Bihar government, is, of course, willing to extend his support. “I have no problem in supporting Nitish as the leader to compete against Modi. Extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures,” he says.

However, all is not well in the grand alliance in Bihar. Every now and then, new unlisted properties of Lalu Prasad and family are making headlines, and a rumour in Patna has it that a close Nitish aide and minister has been leaking information to the BJP. “Nitish is keeping a check on Lalu and he can well force him to accept his leadership,” says NK Choudhary, a professor at Patna University. “The question is, the way he has been flirting lately with the BJP, will other partners trust him as someone who can challenge Modi?”

For regional parties, too, the situation is quite different this time round. On earlier occasions when they joined a national alliance, they did so from a position of strength in their respective states. Now, everyone is fighting their own regional battles of survival against the BJP. For instance, Mayawati, who was once considered a prime ministerial prospect, is on the brink of redundancy. Akhilesh Yadav, who has sidelined his father Mulayam Singh and is still trying to take control of the family, is not doing much better. With a second consecutive win in West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee is today the most sure-footed among regional party leaders. Derek O Brien, Trinamool Congress MP, says he is confident Banerjee will play a crucial role in the BJP’s defeat in 2019. But she is worried about the rising graph of the BJP in her state, and how it has swiftly replaced the Congress and Left as the main opposition. At this juncture, she cannot afford to entertain national ambitions.

Naveen Patnaik, the four-time Chief Minister of Odisha, who until now looked invincible, is also facing the heat. The BJP stole the show in the recently held Panchayat elections in Odisha. The state will go to polls along with the Lok Sabha elections in 2019 and the BJP is trying hard to make a mark there. On April 15th, Modi was in Bhubaneshwar to attend a BJP national executive meeting. His roadshow in Odisha was a resounding success. Besides, Patnaik now faces challenges from within the party with infighting surfacing post the Panchayat poll debacle. Party MP T Sathpathy openly alleged that the BJP was trying to divide the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) before the polls. He even accused party MP Jay Panda of playing into BJP hands. Panda, who on occasion has expressed agreement with steps taken by the Modi Government, was quick to tweet: ‘He speaks with expertise, having once been suspended from BJD and joined another party. I don’t have such experience.’ Patnaik has maintained a clear distance from the Congress and has occasionally aligned with the BJP, but now with the BJP as the main opposition, he is forced to ally with others.

Other regional parties, whatever their past affiliations, would rather back the winning horse. Andhra Chief Minister and TDP President Chandrababu Naidu, who was convener of the UF Government and played a role in bringing all the parties together, has been cosying up to the BJP of late. He has to build a new capital and attract investment into bifurcated Andhra Pradesh and needs Delhi’s blessings. A man with a mission, he has no inclination to join the opposition.

There is, therefore, no political colossus under whose leadership even conflicting parties such as the Left, the TMC and the Congress could join hands. “It will be interesting to see if the opposition parties manage to come together and make it a two-corner fight, but if they make it anti-BJP or anti-Modi, it could backfire,” says Verma. Joining hands solely on the plank of opposing the dominant party has not worked in the past and won’t work now. As Ram Vilas Paswan, Union minister and president of the Lok Janshakti Party, says, “Too many zeroes can’t make a hundred. They will remain zero.”

/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Cover_Blueprint.jpg)

More Columns

How Cubism Became Vernacular in India Shaikh Ayaz

This Alternate Asia Cup XI Will Give Team India A Run For Its Money Short Post

Graphic Narratives that Tell Magical and Relevant Stories Rush Mukherjee