Balochistan: And the Mountains Echoed

ON 22 SEPTEMBER, around 60 people gathered at Rive Gauche in central Geneva, Switzerland. Led by Brahumdagh Bugti, president of the Baloch Republican Party (BRP), and armed with placards saying 'Free Balochistan', 'We Hate Pakistan' and 'Long Live Balochistan', among others, the group marched along the streets in the mid-afternoon sun towards the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 3 km away. The 33-year-old Bugti, the most prominent leader of Balochistan's movement of freedom from Pakistan, was accompanied by Mehran Marri, the Sardar of the largest tribe—called Marri—of that province sandwiched between Sindh, Iran, Afghanistan and Punjab. Also present was Tarek Fatah, a Pakistani writer and analyst.

The march was aimed at drawing attention to a movement that the world had largely forgotten until it got an unexpected shot in the arm from Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 15 August this year. "We held several protests in the past, but no one cared about what we were talking about. We used to record ourselves and send to media houses, but it would appear nowhere," says Shah Nawaz Bugti, spokesperson of the BRP. "But now, a lot of media was there, along with people from different countries who showed interest in our plight. You can call it 'the Modi Effect'."

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Ever since Modi rebuked Pakistan for its handling of Balochistan in his Independence Day speech, Baloch nationalism has had the oxygen of publicity enough to reignite passions for a cause many had begun to presume lost. Baloch leaders across the world have revived the stir with a gusto rarely seen in recent times. That India has kept up the pressure has encouraged them. On 26 September, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj highlighted human rights violations in Balochistan in her special address at the United Nations General Assembly. "This will be an incentive to the Baloch people, as their voice will be heard across the world," says Tarek Fatah, "because when the Indian Foreign Minister speaks, the world listens."

The voice of the Subcontinent's major power, they believe, offers them an unprecedented opportunity to up the ante against Islamabad. "It would be wrong to say that the struggle was not there [earlier]. It is just that the world was ignorant of our fight for freedom and the atrocities on Baloch people in Pakistan," Bugti tells Open over the phone from Geneva, where he has applied at the Indian Consulate for asylum in India.

Balochistan's liberation movement has its origin in the messy manner of the province's integration with Pakistan in 1948 and is fuelled by Baloch alienation, a sense of their aspirations being crushed by the 1947-formed country. Embers of frustration have surfaced from time to time, most recently after the cave-blast killing in August 2006 of Akbar Bugti, Balochistan's former chief minister-turned-rebel and Brahumdagh Bugti's grandfather.

Pakistan's largest province, Balochistan accounts for 42 per cent of the country's land, but, being a largely arid zone of hills and ravines, only 4 per cent of its population. This also means its people have very little say in national affairs. The region is rich in natural resources such as oil and gas, gold and copper, and its location gives it a geo-strategic importance that underlies the current China Pakistan Economic Corridor, a project that the two countries expect will energise their commercial ties and turn Gwadar—the province's principal port—into a trade hub, granting China direct access to the Indian Ocean. While grand plans are chalked out in Islamabad and Beijing, the locals there have seen almost nothing done for their upliftment. Poverty is rampant, by all accounts, and signs of Pakistan's neglect everywhere. The education system has all but collapsed, as also whatever passes for industry. Local leaders have long complained of apathy and worse.

Before it came under British rule in 1839, Balochistan was a vast independent province with four states within it, Kalat, Lasbela, Kharan and Makran, each of them ruled by the leader of the dominant tribe there. During India's freedom struggle, Baloch leaders had supported the Muslim League's demand for Pakistan. While Lasbela, Kharan and Makran were ready to join the new country, Kalat, whose territory corresponds with that of Balochistan today, wanted to proclaim itself independent. According to the Baloch narrative, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who was also Kalat's legal advisor, had agreed to this in principle.

On 11 August 1947, Kalat declared its independence. But in reality, its 'autonomy' had a rider in the form of an agreement signed between Jinnah and Kalat's ruler Ahmad Yar Khan by which Pakistan would inherit the rights—to external affairs, security control and so on—held by the British over Kalat. After 14 August 1947, the fledgling state found itself under Pakistan's control with Jinnah pressing for its formal integration. Yar Khan put up a resistance that was finally crushed by Pakistan's army on 26 March 1948. On 1 April that year, Kalat was made to join Pakistan as its Balochistan province.

Memories of the army's depradations still abound, and calls for freedom have been throttled and silenced with force all through the decades since. Insurgent Baloch leaders have been jailed, threatened and killed, and armed uprisings have been overpowered by Pakistan's army. By the turn of the century, separatists were ready to settle for an autonomy deal within the country that would give Balochs greater control over the region's resources. But Akbar Bugti's 2006 killing in an army attack on his hideout ended those overtures and the Baloch insurgency re-adopted full independence as its aim—with the BRP, launched that year by his grandson, at its forefront.

The area is still overrun by Pakistan's army, whose violations remain a matter of grave concern. Taj Baloch, who runs Human Rights Council of Balochistan from Sweden, claims to have the names of 3,500 people who have gone missing. "What we have is just 5 per cent of the total number. The sources to collect such data are very limited and the actual numbers are very high," he says.

TODAY, EVEN AS the ground situation in Balochistan remains parlous, the freedom movement is mostly in exile overseas. Its leaders have sought asylum in the UK, the US, Canada, Europe and even South Korea. "There were a number of murder attempts on me," says Bugti, who fled to Afghanistan in 2006, "The house next to mine was blown up in Afghanistan. My friends told me I was the target." It was in 2010 that he reached Switzerland. "The Swiss government doesn't allow me to travel anywhere. That's why my movement is very restricted," he laments, "If I get asylum [in India], I would be able to travel to different countries and talk about Balochistan."

Geneva, however, does offer access to international dignitaries, and Bugti gets active before the UN sessions every March, June and September, meeting people, organising protests and speaking at various forums to highlight the Baloch cause. Mehran Marri, Bugti's Dubai-based brother-in-law and the sixth son of Baloch leader Khair Bakhs Marri who died in June 2014, brings the voice of Balochistan's largest tribe to the microphone.

Like Marri, Bugti belongs to families that are among Pakistan's wealthiest. "Lots of people question our funding. I own 100,000 acres of agricultural land across Pakistan, apart from other properties," says Bugti. "I finance almost half the party's expenditure. The rest comes from party members in different countries, especially in the Middle East."

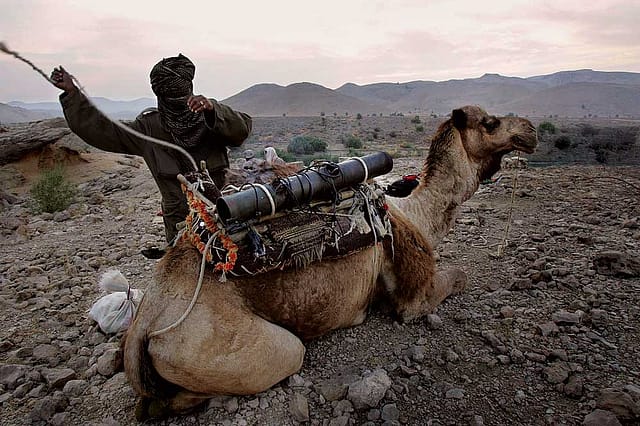

Among the other formations fighting the cause is the Balochistan Student Organisation-Azad. Founded in 2002 by Allah Nazar, a medical student keen on an armed struggle to secure a 'Greater Balochistan' that would include some parts of Afghanistan and Iran, the BSO-A has been mobilising young Balochs for the cause both in Balochistan and overseas. After it was banned by Pakistan in 2013, Nazar moved to a secret retreat. While the BSO-A disavows the use of arms now, the party expresses sympathy for those willing to deploy such means for Baloch freedom. "Some of our people took gun, because Pakistan forced them to do so," says Karima Baloch, the 32-year-old president of the BSO-A, speaking from Toronto. "They are also fighting like us."

As a party worker in Pakistan, Karima Baloch would tour the country draped in a hijab waving a 'Free Balochistan' banner. Banuk Karima, as Balochs fondly came to call her, quickly gained popularity for what they saw as a daring campaign of open defiance. In March 2014, she was travelling with party president Zahid Baloch and two other female members, when they were waylaid and their president was abducted. "I couldn't recognise who they were," she says of the abductors, "I and the other two, being female, were left." There has been no word or trace of Zahid Baloch since. A month after the incident, a student leader called Lateef Johar sat on a hunger strike outside Karachi Press Club for 46 days for the party president's release, but to no avail. "They threatened and even tortured me, and I eventually had to end my hunger strike," says Johar, who is also in Toronto.

Last year, Johar and Baloch were advised by close friends to leave Pakistan. Neither will disclose how they got there. "The details of my escape could cause trouble for my family back in Balochistan," says Johar, who reached Toronto last September. Karima Baloch got there a couple of months later. "The first thing I did after landing in Canada was to remove my hijab," she says, "I had no fear, and that is when the world saw me for the first time."

The BSO-A has recently forged an alliance with the Baloch National Movement (BNM), another political organisation, to form the Balochistan Nationalist Front with Karima Baloch as its chairperson. Her days are quite hectic, she says, as she keeps track of developments and formulates a strategy for the alliance to press ahead with the cause while it remains in the spotlight.

"Today, there would hardly be any youth in Balochistan who is not part of our party," claims Johar, who assists Karima Baloch in her work apart from keeping party workers back at home engaged. On the matter of funding, he says, "Every party member donates money to the party fund as per his or her wish, and we also organise donation camps. We don't get funds in abundance and hence we spend the money logically."

On Raksha Bandhan this year, Karima Baloch addressed Modi in a video message from Toronto, hailing him as a 'brother of Baloch women'. "As the head of the world's largest democracy, he raised our issue for the first time," she explains. "Not just me, but all Baloch women consider him a brother. There couldn't have been any better day to extend our good wishes."

The other party in the alliance, the BNM, is led by Hammal Haidar, an Oxford-educated Baloch who had moved to the UK as a child and is now a British citizen. Officially the BNM's foreign representative, he has been leading protests in London and other places in the UK against Pakistan's control of Balochistan. "I keep travelling for party work and meeting Baloch people in different countries," says Haidar, speaking from Canada, where he is on tour to address hall meetings and draw Baloch activists together who have been working solo. "It is better to join an organisation than work independently, as your strength increases with the support of other members," he says.

This quest for unity is recent. The movement has always had disparate groups in operation. The BRP and BNF, for example, are not even in contact with each other. Many activists claim no allegiance to any group. "I work under the banner of my NGO, World Baloch Women's Forum," says Canada-based Professor Naela Quadri, a filmmaker and writer who is not affiliated to any group, "I don't feel the need of joining any party."

Are these divisions the reason the movement went largely unnoticed for so long? "I don't think so," says Bugti, "Every freedom struggle had different parties and individuals working differently, but they work for a common cause." He cites the example of Gandhi and Bhagat Singh, who fought the British in different ways.

With their cause getting a global wave of attention, Baloch nationalists hope, their dream of freedom will take a leap for realisation at long last. "There could not be better time for Balochs than now," says Bugti, "We don't want to miss it."