How Bad Is the Economy?

The fiscal year 2008-09 is at its end, and everyone is cheering. Is this premature?

The fiscal year 2008-09 is at its end, and everyone is cheering its demise. Though we won't know for another couple of months, the news (conveniently after the election results are out!) will not be good. It is highly likely that the last two quarters will show the lowest growth in GDP that the economy has seen, ever! (More accurately, since quarterly records became available in 1996). The previous six month low was in the second calendar quarter of 1997, or the quarter just before the Asian crisis. At that time, the six month growth was only 0.9 per cent; end March 2009, the six month growth might be negative.

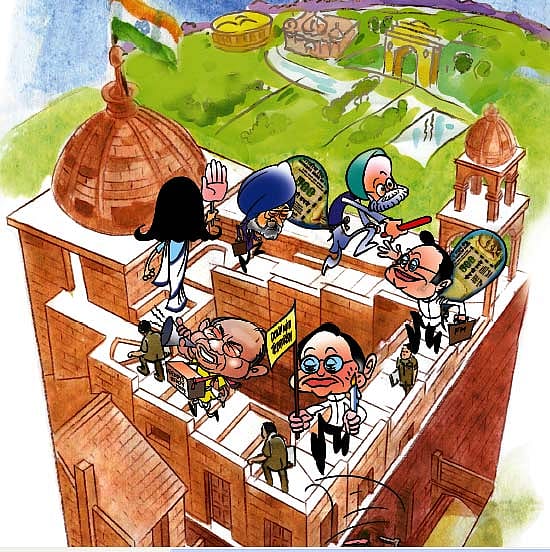

That is the bad news, and news that all of us have lived through. That it has been so bad is a large function of the international crisis; a not insignificant part is because of some particularly misguided policymaking and policy response in India. The response can be analysed through three layers of policymaking—the Congress party, Ministry of Finance and Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The first two are part of the same parcel, with the difference that the ideological parameters are set by the more-than-leftist Congress high command.

The ideological space occupied by this high command was revealed by Ms Sonia Gandhi's assertion that India had escaped the financial crisis because its banks were in good shape—and the reason its banks were in good shape was because of her mother-in-law Ms Indira Gandhi's bank nationalisation policy of 1969!

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Sure, the international crisis has affected the domestic economy, but the slowdown has been exaggerated by a mishandling of economic policy. Which is tragic given that Dr Manmohan Singh is the prime minister, the same individual who helped usher in economic reforms in 1991.

So the first aspect of how bad is it is the ideology of denial on part of the Congress party. Ever since the crisis started, it has trotted out one 'expert' after another (including some pliant foreign 'experts') to shout the party line—India has really not been affected by the global financial crisis. "Look, our growth rate is down to 5.3 per cent while most countries have that number with a negative sign."

The quick answer to this assertion is that for developed countries, the growth rate number is for the particular three months in question. For example, the minus 6.2 per cent growth rate reported for the US for the October–December 2008 period is a decline in GDP in October–December of 1.55 per cent (one fourth of 6.22) from the GDP level during July–September 2008.

If the US growth for the fourth quarter were calculated according to the Indian method, then the US economy, the one hardest hit by the recession, would have shown a decline of only 0.8 per cent. India by the same calculation shows a positive 5.3 per cent. The difference between 5.3 and minus 0.8 is a lot less than the difference between 5.3 and minus 6.2.

The point of this laboured calculation is to illustrate, and emphasise, that the (malign) neglect policy of the Government, possibly induced by looking at the wrong data, has made the policy response worse. By looking at the year-on-year GDP growth rate, the Government boldly calculated that it did not need any additional fiscal stimulus at the time of the interim Budget in mid-February. That it soon reversed itself a week later, without any new information, is a sign of gross incompetence, and much more.

What has been genuinely scary about the Congress party response to the crisis is its arrogance combined with incompetence. Until 26 November 2008, the Congress believed it had fooled the people by having a 'reform' oriented Mr PC Chidambaram as the finance minister. With 26/11, one of the two Congress lies got exposed—certainly one of the two ministers, finance or home, was a bumbler and had to go. Shivraj Patil went, and there was a vacancy at finance. This is where the arrogance came to the forefront. First, the Congress made us all believe that the best way to cope with the international crisis was to have Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh handle two portfolios. Then the PM had to have heart surgery and it is ambiguous whether the two phenomena are related. The Congress chose to have nobody run the finance ministry, and then chose a traditional politician, also with another key portfolio, to run finance. No surprise that the acting finance minister made a complete mess of the interim Budget. Why, in all of this, they could not find a competent person within the Government to be finance minister is beyond most people's comprehension or imagination.

In all fairness, the Congress party (unofficially) had a response—look, we cannot choose a technocrat, or a non-party smart person, to be the finance minister because this is such an important post! So why leave it vacant? That this nonsense could not emanate from the PM is made obvious by the observation that the PM himself was a technocrat who was offered the plum job by another Congress leader, Mr Narasimha Rao. Perhaps the obvious explanation is that an insecure Congress leadership cannot appoint anybody on merit, or on what the nation needs. And this last part is pertinent in our examination of whether the present Congress Government has made a bad situation worse. It most certainly has.

But one would be less than honest if one did not apportion a large portion of the blame to a subsidiary of the Ministry of Finance, the RBI. This is another organisation which, in its obstinacy and ineptness, has read the entire Indian growth story wrong. Both when the economy was doing well, and when not, the RBI made erroneous judgments. As far back as April 2005, the RBI came out with this shocker: the economy was overheating. For the next four years, the economy continued to 'overheat' to grow at a faster rate, to be investment led, to not have any additional inflation. None of this changed the obstinate ideology at the RBI. Thankfully, the central bank is no longer claiming (as it initially was) that the increase in inflation to 12 per cent plus in mid-year 2008 was due to 'overheating'. I think the RBI has now grudgingly acknowledged that most of the inflation was imported into India, as it was in most parts of the world.

Now that we are in the midst of the greatest recession, and slowdown, the RBI continues to talk of overheating and incipient inflation. It also hints that because it has brought the overnight rates to as low as 5 per cent, India might possibly be in the midst of a liquidity trap! No one has heard of real lending rates of 13 per cent plus in the midst of a liquidity trap, yet the obduracy at the RBI believes so.

So no matter where one looks in India, the news is not good. So does that mean that the Indian economy is doomed because of our bad administrators? Most emphatically not.

Globalisation, and our entry in it, has brought us a large part of our gains, and globalisation (albeit aided and abetted by the authorities) has brought us the slowdown. A reasonable case can be made that the developing countries, led by China and India, have probably already seen their worst quarter (either October–December 2008 or January–March 2009). These two economies should lead the world economic recovery.

Analysts sometimes question this emphasis on these two population giants and point to the fact that the two economies together make up only a quarter of US GDP. True. However, the recovery being mentioned is in terms of GDP growth, and if the US grows at 1.5 per cent, these two have to grow at only 6 per cent to make their contribution to world growth the same as that of the US.

My admittedly risky forecast for Indian and world growth is as follows. For fiscal year 2009-10, India should grow at 7 per cent plus, and about the same for China. The Western world should join the recovery bandwagon latest by the end of the year. The stock markets, if they are true to historical form, should start rallying three to six months before the economy bottoms. Which means the Indian stock market should be doing well now. This is not exactly happening, though it is occurring in China and East Asia. But then, India has elections to consider!