Beijing Backs Down

THE CHINESE COMMANDER WHO HAD MET the Indian team at Moldo on China's side of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) for the sixth round of talks between military commanders on September 21, 2020, was in a somewhat pensive and distracted frame of mind. Differences between the two sides should be resolved by military leaders, he had said, an indirect but obvious reference to India's surprise military operation on the intervening night of August 29-30 that gave Indian troops control of the Kailash Range heights to the south of the Pangong Tso lake. Offering a clear line of sight of the Chinese military build-up, the audacious move neutralised the advantage Chinese troops had held since border tensions flared in May-June. Control of crucial features on the Kailash ridge would seriously disadvantage the People's Liberation Army (PLA) units if the face-off escalated. It was not hard to figure out why the Chinese general seemed out of sorts.

Earlier, when S Jaishankar had met Chinese State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Moscow on September 10, the Kailash operation had given the Indian external affairs minister strong bargaining chips as till then the odds along the LAC had put India on the backfoot. "The two Foreign Ministers agreed the current situation in the border areas is not in the interest of either side. They agreed therefore that the border troops of both sides should continue their dialogue, quickly disengage, maintain proper distance and ease tensions," said a joint statement after the meeting. After the military commanders met a few days later, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) said, "They [Indian and Chinese commanders] agreed to earnestly implement the important consensus reached by the leaders of the two countries, strengthen communication on the ground, avoid misunderstandings and misjudgements, stop sending more troops to the frontline, refrain from unilaterally changing the situation on the ground, and avoid taking any actions that may complicate the situation."

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The facts on the ground had changed. Not just along the south bank of Pangong but on the spurs, or the Finger 1 to 8 area, and on the north bank too. A little over three months later, Chinese troops vacated the spurs, removing shelters and dismantling other military infrastructure. The haste with which the Chinese left seemed to confirm the view of some Indian military commanders that occupation of the spurs exposed to hostile weather offered no real gain, certainly not since the Kailash move.

THOUGH THE JUNE 15, 2020, Galwan clash that claimed the lives of 20 Indian soldiers was not premeditated, it did make it evident that India would not baulk at casualties or hesitate from inflicting a similar cost on the Chinese. The scale of the Kailash action that followed signalled a preparedness to take risks and was not part of the copybook China was used to. For several years, and increasingly so 2010 onwards, the PLA found it expedient to intrude along the LAC, causing severe embarrassment to successive Indian governments. The so-called salami-slicing tactics were free of any significant cost as they led to Chinese troops squatting in an area for long periods and pulling back only after protracted negotiations. In 2013, PLA's incursion in Depsang had led to the Manmohan Singh government facing heat in Parliament before an agreement was reached. In September 2014, just ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping's visit to India where he was to be hosted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a PLA incursion in Chumar had led to an embarrassing standoff. In August 2018, China had created a similar situation in Demchok close to where the Indus flows into India from Tibet. Even though the trespasses were "vacated", Indian troops were obstructed in patrolling the Demchok and Depsang areas. The regularity of Chinese infractions—in the Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh sectors as well—signalled Beijing's assessment that the relative restraint of the 1990s and early noughts was no longer required. The gap in economic and military power between India and China had widened and it was felt that the PLA's actions could carve new alignments on the ground and remind India that it held a weak hand.

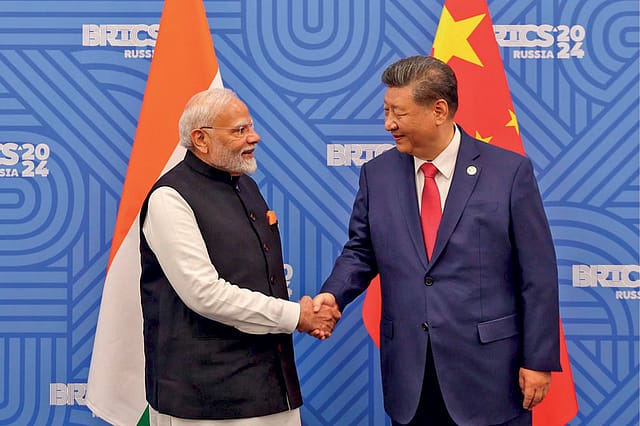

More than four years later, Beijing's calculations did not quite pan out. On September 21, India and China confirmed that an agreement had been reached to complete disengagement—and, importantly, restore patrolling—in eastern Ladakh, restoring the situation as in May 2020. The dramatic breakthrough led to a Modi and Xi bilateral meeting on October 23, the first since 2019, at Kazan in Russia on the sidelines of the BRICS summit. In his remarks, Modi clearly underlined India's bottom line, saying, "Mutual trust, mutual respect and mutual sensitivity should be the basis of bilateral relations."

"Welcoming the recent agreement for complete disengagement and resolution of issues that arose in 2020 in the India-China border areas, Prime Minister Modi underscored the importance of properly handling differences and disputes and not allowing them to disturb peace and tranquillity," the MEA statement said.

The Chinese statement said, "The two leaders commended the important progress the two sides had recently made through intensive communication on resolving the relevant issues in the border areas. Prime Minister Modi made suggestions on improving and developing the relationship, which President Xi agreed to in principle… The two sides were of the view that this meeting is constructive and carries great significance. They agreed to view and handle China-India relations from a strategic height and long-term perspective, prevent specific disagreements from affecting the overall relationship…"

Some commentators noted that the Chinese did not refer to an "agreement" on border tensions but Beijing has not objected to India's use of the formulation in any statement. The Chinese statement endorses the revival of the Special Representative-level dialogue on the "boundary question" and backs talks at the level of foreign ministers and other officials to "bring the relationship back to sound and steady development at an early date."

The inclusion of Demchok and Depsang, areas the Chinese argued pre-dated the 2020 events, in the disengagement and patrolling agreement, is significant. It appears the Indian insistence that these "legacy issues" be part of the deal was conceded by China. Following the October 21 Indian statement on agreement to restore patrolling arrangements, a Chinese spokesperson confirmed the developments, stating the two sides have reached a resolution on "relevant issues" and that China gives its "positive approval" to this. "In the next stage, we will properly implement the resolution with the Indian side," said a Chinese foreign ministry official. The details of the patrolling arrangements will be worked out between the two militaries and are expected to deal with protocols to ensure pushing and shoving between troops—that intensified into shots being fired in 2020—does not happen and soldiers are no longer in close proximity along the LAC. India achieved the first step of what the Modi government has repeatedly iterated: normalisation of the border is a pre-requisite for restoration of bilateral ties. For its part, China would need to rethink its view that border tensions are "localised" and can be compartmentalised.

India-China relations are far from normalised and Chief of Army Staff General Upendra Dwivedi pointed to a serious trust deficit that needs to be eradicated while commenting on the developments that will require China to faithfully implement the disengagement. According to Colonel (retired) S Dinny, editor of Chanakya Forum, China's gains from the military standoffs in eastern Ladakh since 2020 are meagre. "If the idea was to discourage India from building up infrastructure along its side of the LAC, the opposite has happened. If it was unhappiness over India's moving closer to the US, then Indian-US ties have deepened. If the idea was to show who is boss, then the resoluteness of the Indian response has surprised the Chinese leadership," said Dinny, who has served in the Ladakh area.

The decision to mass 50,000 troops in response to the PLA's aggressive actions and Modi's preparedness to extend the conflict to economic actions is evidence that China's coercive strategy has failed. The long and undefined LAC remains vulnerable to sudden intrusions but China's leaders would need to consider that the tactics are now yielding diminishing returns. The mobilisation of troops on both sides and improved means to monitor the ground situation means any move is quickly countered. Tactical deployment, better intelligence and year-round deployment saw Indian troops repulsing a Chinese bid to overrun border outposts in the Yangtse region of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh in December 2022. It was hard to escape the conclusion that the situation along the LAC was a stalemate and did not suit China. A 'mutual' disengagement is a useful exit strategy without calling it a face-saver. China can no longer assume that India's actions will be constrained by concerns about a likely escalation.

THE FIRST PUBLIC evidence of a possible thaw came by way of China appointing Xu Feihong as ambassador in May 2024, after a gap of 18 months when the office was vacant. In August, Xu wrote an article about the "five mutuals"—mutual respect, mutual understanding, mutual trust, mutual accommodation, and mutual accomplishment—that can bring India-China relations back on track. This would not be the first time that a Chinese diplomat has penned conciliatory and encouraging words about India-China relations and it was not until more high-level contacts between National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval and Jaishankar on the Indian side and Wang on the Chinese that the possibility of a breakthrough seemed likely. Though the exact motives of the Chinese leadership are not easy to fathom, the disengagement might signal Beijing's acknowledgement that the Modi government is firmly in the saddle for another term. The possibility of a weaker coalition government having been ruled out, political stability in India could have a bearing on China's decisions. Progress has been incremental with successive disengagement in the Galwan, Pangong Tso, Gogra and Hot Springs areas. The Indian and Chinese announcements this week can set the stage for a larger de-induction of forces along the LAC which will signal that both sides no longer anticipate a rapid escalation of border tensions into military conflict. Former officers familiar with the Ladakh sector point out that the patrolling protocols need a review to rule out a return to old tensions. In 2013, when Manmohan Singh visited China, border protocols were indeed enhanced but failed to prevent incursions, providing strong evidence that India needs to demonstrate deterrence and a capacity to confront intruders.

The buffer zones created at the friction points have served to move troops away from eyeball-to-eyeball contact and while India stepped back, so did China from points that it claims fall within its perception of the LAC. It was not India alone that gave up patrolling to points within buffer zones as the PLA did the same. In certain areas, both PLA and Indian troops have patrolled without setting up permanent markers and border posts. The ranges in the Ladakh Himalayas are indistinguishable to the naked eye and without military maps and satellites there is no way of knowing where the LAC runs. The restoration of patrolling protocols will be based on patterns the two militaries recognise and agree not to violate and which do not amount to attempts to create new alignments. Dinny points out that Chinese positions along the LAC go back to 1962 and its aftermath. The intrusions in Demchok or Depsang had added a few kilometres and in other places the ingress is not much more than a few hundred metres. "They have been on their claim lines for years," he said. Statements that the Chinese have taken over hundreds of square kilometres of Indian territory have been contested by Jaishankar, who said this had happened in 1962 and not recently.

Not long after he became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Chinese Military Commission in late 2012, Xi undertook a series of steps that signalled a more assertive power projection which was a sea change from the caution of previous leaders best articulated by Chinese proverbs like "Bide your time, hide your strength". After having taken down internal rivals, many on corruption charges, Xi felt the time had come for China to flex its muscles within its 'legitimate' zone of influence, a view that led to serious friction in the South and East China Seas. As regards India, the motives could include a desire to set out China's red lines. These typically mean India's infrastructure build-up is a 'threat' to China's security interests in the Karakoram region and New Delhi must defer to Beijing's role in Asian and global affairs. As things stand, Xi's policies have only brought China's neighbours and rivals together. The US has invested heavily in the Quad as an informal alliance to counter China and the engagement of European nations in the Indo-Pacific has risen exponentially. There are misgivings within ASEAN about China's actions as it seeks to unilaterally impose its nine-dash line formula.

In a thoughtful and well-informed essay titled 'China's Age of Counter-Reform', Fordham Law School Professor Carl Minzner argues China is economically slowing down and closing up ideologically and is closer to Mao's one-man rule—with its consequent ill effects—than might be apparent. "Security officials regularly fan fears of foreign espionage, particularly around April 15, designated since 2016 as National Security Education Day. A 2023 anti-espionage crackdown on consulting firms shocked foreign corporations trying to conduct statistical research and due diligence… New laws criminalize defamation of regime-designated martyrs and heroes. Access to commercial and academic databases has been curbed," Minzner writes. He adds that on the economic front, "China continues to slow. Covid lockdowns, a rapidly aging population, and the implosion of a massive property bubble have taken a toll on the once buzzing economy. Annual growth, which registered 6.7 percent as recently as 2016, has steadily fallen. For 2024, the official rate is expected to come in at no higher than 5 percent (the IMF projection) and could be as low as 3 percent (per the New York–based Rhodium Group)." Though the inner workings of the Chinese leadership are subject to speculation, there might be strong incentives for China to tone down its hostility towards India.

The gains of the India-China disengagement agreement will need work on the ground to become more permanent and this includes respect for border protocols and a purposeful discussion on processes to resolve differing perceptions about the LAC. The initial rounds of negotiations between military commanders and at the diplomatic level following the Galwan confrontation were tough and brutal, according to sources familiar with the events. India repeatedly stressed China had to reverse its aggression and the time for unilateral action along the LAC was over. It took a while, but the message did get home. There is little room for charity in international relations and states achieve outcomes on the basis of an unsentimental commitment to national interest and the strength of their capacities. This rule has endured through the history of human conflict.