The Last of Them

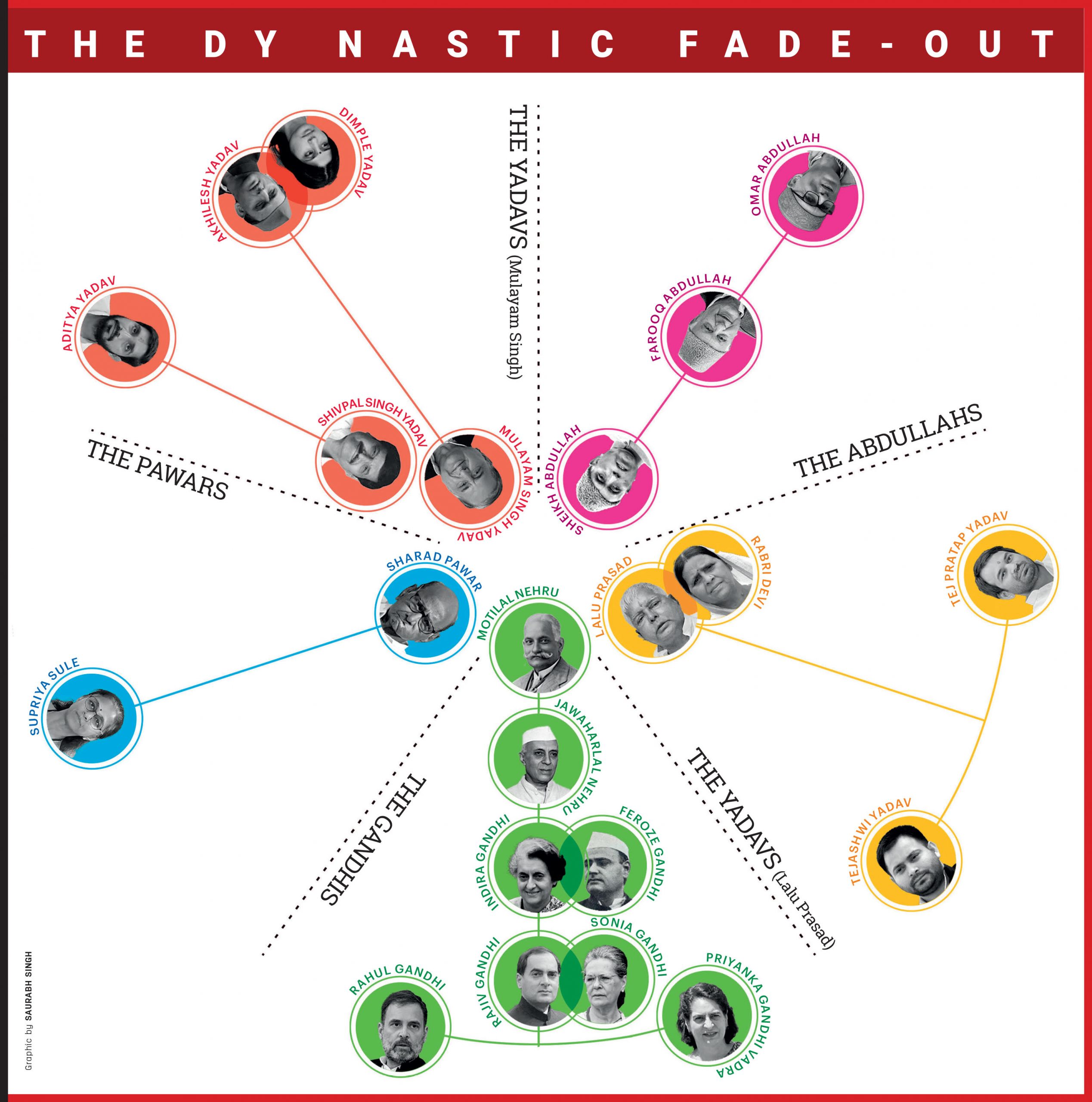

Why certain surnames are no longer an asset in indian politics

/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Lastofthem2.jpg)

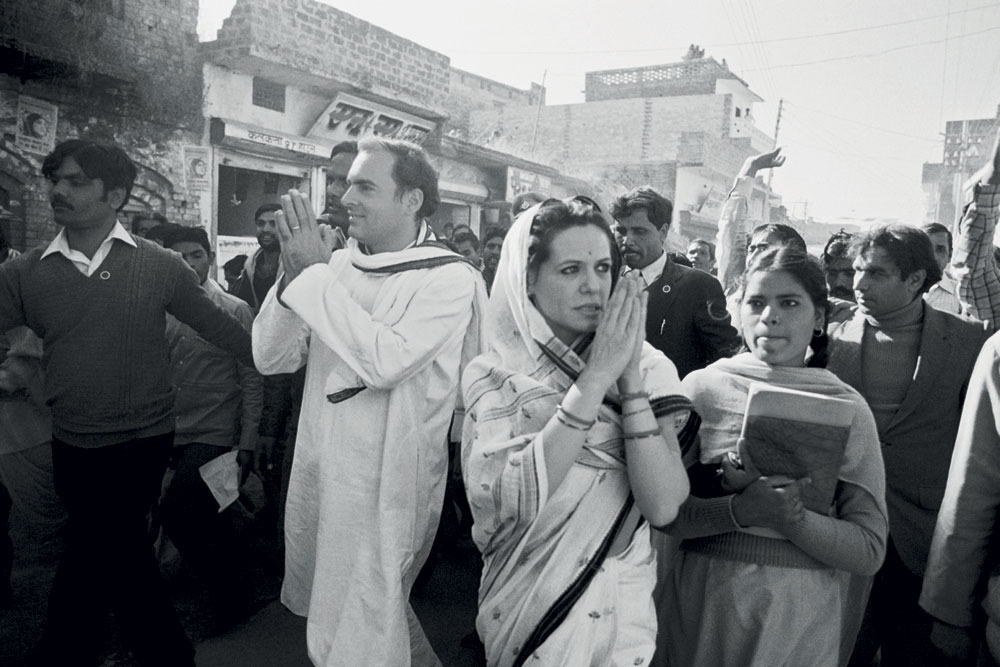

Priyanka and Rahul Gandhi on a roadshow in Wayanad, April 3, 2024 (Photo: AFP)

A CLOSE LOOK AT THE DECLINE AND fall of dynasties or empires, both in India and elsewhere, shows that one of the key reasons for their tragic end is inefficiency. True, exaggerated sense of self-importance and injured pride endure long after they slide towards the precipice of an inevitable doom. This historical pattern was conspicuous in dynasties that include the Mughals. The Mughal Empire had contributed nearly 25 per cent of the world’s GDP during Aurangzeb’s reign and then, following his death in 1707, it went on the slippery slope towards a massive and irreversible fall, thanks to a creeping rise in incompetence and blunders. The rule of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, was confined to a small tract that led to a saying in Persian—Sultanat-e-Shah Alam, az Dili ya Palam (the empire of Shah Alam is from Delhi to Palam, a suburb of the capital).

Rahul Gandhi’s primary choice of retreat to a safe seat in the South is confirmation of the fear in the family and the once-upon-a-time grand old party—that he is possibly the last in the family to exercise power in national politics

Funnily enough, even in modern times, such tragedies make it appear as though centuries coexist. The fate of various Indian political dynasties on the brink now is proof of the cycle of rise and fall of influential families that once presided over the destinies of millions even in the democratic world. A series of resounding and recurring political setbacks and isolation in the larger, national scheme of things suggests that several of these entities that had once dominated our mindspace are on a downward spiral, staring at insignificance and obscurity.

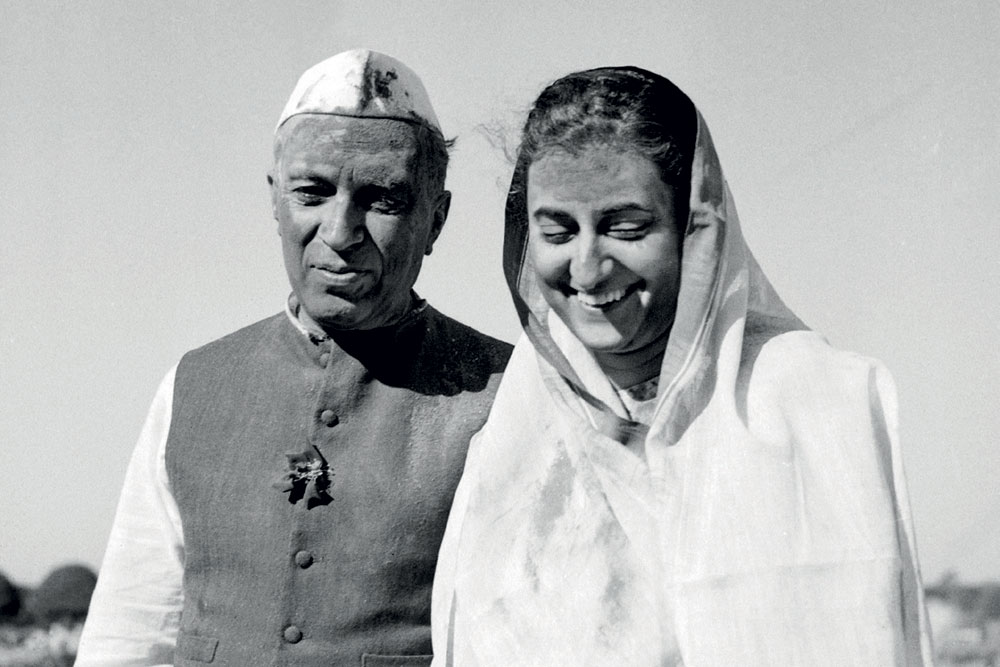

The ancestors of the Nehru family, which enjoyed political heft from the last decade of the 19th century in British India to 2014, had migrated from Kashmir in the 18th century, in first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s own words, to seek “fame and fortune in the rich plains below”. Finally, the family settled in Allahabad and yes, they did acquire fame and fortune, starting from the time of Jawaharlal’s father Motilal who was an early president of Congress and a wealthy man with powerful friends. Thanks to Mahatma Gandhi’s blessings, Jawaharlal Nehru went on to become the first premier of free India, engendering a dynasty that held the reins of Congress, which was destined to rule India for decades on its own and as the head of coalitions. In the process, the family, which produced three prime ministers who together ruled India for 36 years, remote-controlled a Congress-led coalition for another 10 years and had the party in its thrall all these decades except for a brief period, had acquired loyal constituencies—also called pocket boroughs—in the Hindi heartland from where their wins were a given whether or not they did anything for the people. Between them, Nehru and his sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit had won from Phulpur in Uttar Pradesh (UP) until the end of the 1960s. Yet, since 1989, Congress has not won from that Lok Sabha constituency even once.

In Amethi, a constituency created in 1967, the family had secured wins in several elections starting with Sanjay Gandhi, then Rajiv Gandhi, and later Sonia Gandhi as well as Rahul Gandhi. The only occasions the family didn’t represent this seat were when Congress candidates Vidya Dhar Bajpai won in 1967 and 1971, Satish Sharma in the 1991 bypoll (after the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi) and in 1996, and when Janata Party won the seat in 1977 (until 1980), and Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Sanjaya Sinh in 1998 (until 1999). Which means, since 1980, when Sanjay Gandhi, son of Indira Gandhi, won the seat, the constituency had elected either family or its loyalist Satish Sharma for 39 years, except for one year. Then in 2019, Rahul Gandhi lost to BJP’s Smriti Irani who is seeking re-election this year.

In the last General Election, Rahul Gandhi, the Nehru-Gandhi scion, had to contest from Wayanad in northern Kerala, fearing a drubbing in Amethi where he, as a section of Congress and the family had rightly expected, was trounced by Irani. This time round, Rahul has chosen to contest from Rae Bareli, another pocket borough in UP, and has deputed a non-family Congress leader, KL Sharma, to take on Irani in Amethi. The loss of Amethi for the family is confirmation of not only its dwindling fortunes but a debilitating fall in national politics.

Now, take Rae Bareli which had, since 1952, the year of the first elections, non-Congress representatives barely for six years—first when Raj Narain defeated then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1977 (until 1980) then when Ashok Singh of BJP held the seat from 1996 to 1999. Nehru family members who won from the seat include Indira Gandhi’s husband Feroze Gandhi, Indira herself, and Sonia Gandhi. Interestingly, after her ignominious defeat at the hands of Narain in 1977, Indira Gandhi had contested from the south, from Karnataka’s Chikmagalur. In 1999, Sonia Gandhi had contested from two seats, Amethi and Bellary in Karnataka. Rahul moved further south to a constituency where Congress is unlikely to face defeat thanks to it being the stronghold of the Indian Union Muslim League, an ally.

Rahul Gandhi decided to contest from Rae Bareli—where elections will be held along with Amethi on May 20 in the fifth phase—at the last minute, opting initially to stick to Wayanad alone. He changed his mind not to further demoralise the Congress ranks who are perturbed that none of the members of their first family is contesting from the Hindi heartland which holds the key to electoral triumph. Yet, his primary choice of retreat to a safe seat in the south is confirmation of the fear in the family and the once-upon-a-time Grand Old Party—that he is possibly the last in the family to exercise power in national politics.

Inside SP, they often compare Mulayam Singh’s plight to that of Shah Jahan who was put under house arrest by his son Aurangzeb. Yadav senior, a generous man who was known to help the needy whenever approached, was given a paltry pension of sorts by his son Akhilesh

Rahul Gandhi has been leading a tepid campaign in the face of an aggressive BJP blitz led by its spearhead Narendra Modi. Surprisingly, his priorities looked skewed. Sample this: on April 28, ahead of the crucial third phase of polls on May 7 in multiple states, including UP and Madhya Pradesh and others, he was in Odisha’s Kendrapara Lok Sabha seat where the only occasion his party had won was in the 1952 General Election. He has also laid emphasis on divisive agendas of caste and on blaming celebrities for reportedly backing BJP, besides making uninformed pronouncements—including stating that caste elitism is inherent in the Indian bureaucracy. He seemed oblivious to the fact that the Indian bureaucracy has worked more years under his family’s spell than that of any other political entity.

What comes to the fore is his lack of focus and a sense of pessimism combined with wounded pride, traits common to dynasties that are, in all likelihood, descending into chaos.

ANOTHER DYNASTY FACING an existential dilemma is the one that was built from scratch by Mulayam Singh Yadav who was groomed in the anti-Congress, socialist politics of the 1960s. A schoolteacher in Mainpuri, UP, he took a plunge into politics and grew as a politician under the guidance of the likes of Ram Manohar Lohia, Raj Narain, Chandra Shekhar, et al. He became an MLA at the age of 28 in 1967 and then chief minister of UP in 1989, aged 50. A former wrestler, Yadav went on to become Union minister and UP chief minister on multiple occasions, riding the post-Mandal churning in UP politics. He continued to reign in the state after almost coming close to becoming prime minister in 1996 and led his Samajwadi Party (SP) to electoral triumph in the 2012 Assembly polls. That year saw his son Akhilesh Yadav become chief minister of UP.

SP was never the same again on Akhilesh’s watch. In fact, the young Yadav, who had never won an election on his own, began to sideline his father following his election as party president. In party circles, especially among the old guard close to Mulayam, there was much resentment about the way the son had treated the father who died in 2022 after winning his last election from Mainpuri in 2019. Inside SP, they often compare Mulayam’s plight to that of Shah Jahan who was put under house arrest by his son Aurangzeb. Yadav Sr, a generous man who was known to help the needy whenever approached, was given a paltry pension of sorts by the son, and this meant much distress and anguish for the ailing father who still had people approaching him for help, including financial support. Distraught, Mulayam had to turn to UP businessman Sanjay Seth for assistance. Before his death, Yadav Sr requested a meeting with an influential Union minister who not only agreed to meet him but did so at Mulayam’s own place, saying that a senior leader of his stature didn’t have to visit the minister at his advanced age. Mulayam had only one request: that the minister take care of Seth after he was gone. Seth, who was Rajya Sabha member initially from SP and joined BJP in 2019, has been re-nominated as member of the House this year.

The Yadav family of Bihar faces a similar predicament, having lost its sway over OBC votes, including a section of Yadavs, to BJP. But the heyday of the patriarch, Lalu Prasad, was over long ago. Prasad has not been able to revive himself in state politics after 2005

Akhilesh Yadav did not fare well on his own in the 2017 and 2022 Assembly elections, and did badly in the 2019 General Election too, despite a grand alliance with Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). In the previous General Election, SP won only five seats, including that won by Mulayam. In the SP stronghold of Kannauj, which Mulayam, Akhilesh and wife Dimple had represented since 1999, Dimple Yadav lost to BJP’s Subrat Pathak in 2019. She was elected to Parliament in a sympathy wave in the bypoll held after Mulayam Singh’s death in 2022 in Mainpuri.

Kannauj is where the great socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia was elected to Lok Sabha in 1967. Akhilesh Yadav had won from there in 2000, 2004, and 2009. After he was named chief minister in 2012, Dimple Yadav won the byelection unopposed, and she won once again in 2014—until losing it to BJP after 21 long years. In the 2022 bypoll, BJP also won in Azamgarh, the Lok Sabha seat won by Akhilesh in 2019 which he had to vacate since he was elected as member of the UP Assembly.

This time round, like Rahul Gandhi, Akhilesh Yadav is buffeted by crises within and without, including his growing irrelevance as a politician and regional heavyweight amidst charges of nepotism and lack of shrewdness. His seat distribution has come under flak from within the party and from sympathisers. For reasons best known only to him, he has changed candidates in 12 seats in the state, including twice in Meerut, besides other seats like Baghpat, Gautam Buddh Nagar, Badaun, Sultanpur, Bijnor, Moradabad, Shahjahanpur, Kannauj, Lucknow, and Shravasti.

Now, the SP president faces headwinds following the loss of Yadav-dominant constituencies in UP, such as Firozabad and Badaun. In Badaun, SP has fielded Shivpal Singh Yadav’s son Aditya Yadav. In Kannauj, where Akhilesh is contesting from, Muslims constitute 15 per cent of the electorate and Hindus 83 per cent, among whom Yadavs are 16 per cent, Brahmins 15 per cent, Rajputs 10 per cent, Scheduled Castes (SCs) 22 per cent, and the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) 17 per cent. With BSP not aligned with SP this time, it isn’t an easy sail for the SP scion who is facing the biggest challenge of his career yet.

THE OTHER ONCE-powerful Yadav family in the neighbouring state of Bihar faces a similar predicament, having lost its sway over OBC votes, including a section of Yadavs, to BJP. But the heyday of the patriarch, Lalu Prasad, was over long ago, at the beginning of this century. Prasad, who became chief minister of Bihar in 1990 and helmed a lawless regime that forced wealthy business classes to flee from the eastern state, has not been able to revive himself in state politics after 2005 when his former comrade-in-arms Nitish Kumar emerged as chief minister and went on to become the longest-serving chief minister of the state with BJP’s backing and his own party Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD). Lalu Prasad did steer state politics when his wife Rabri Devi was chief minister between 2000 and 2005 and earlier in her two short terms. His younger son Tejashwi Yadav—Lalu Prasad and Rabri Devi have nine children, seven female and two male—had held the deputy chief minister’s post from 2015 to 2017 and later from 2022 to 2024.

With the rules of engagement changing rapidly, especially following the revocation of Article 370 that bestowed special powers on Jammu & Kashmir, the Abdullah dynasty has lost its sting and has diminished in appeal

In a case of receiving their just deserts, Lalu Prasad (and family) had always been in the eye of the storm when it came to corruption scandals from early on in his career and these continued to haunt him and the family, in addition to seemingly insurmountable political challenges in the state. Open had reported earlier that the Directorate of Enforcement (ED) was in advanced stages of inquiry into the land-for-jobs scam, allegedly involving the family of Lalu Prasad, which took place when he was Union railways minister in the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. The scam pertains to handing out jobs to people in exchange for land plots that were transferred at nominal prices to the relatives of the RJD leader. The candidates who got jobs in railways, directly or through their immediate family members, allegedly sold land to the Yadav family at highly discounted rates. Officials joke about the naiveté of those behind this ‘scam’ who didn’t seem to realise how easily traceable the money link was, the same reason Lalu Prasad landed in trouble in the fodder scam of the 1990s when he was chief minister. Back then, an official report had noted: “Cattle were transported on scooters, police vans, oil tankers, and autos by the suppliers.”

With none of the other children, with the exception of Tejashwi Yadav, displaying political skills—which in any case are too rusty to be put to use in the fast-changing national politics—it looks like sunset time for the once-formidable Yadav clan of Bihar.

VERY FEW THINGS are what they seem, especially when it comes to Kashmir.

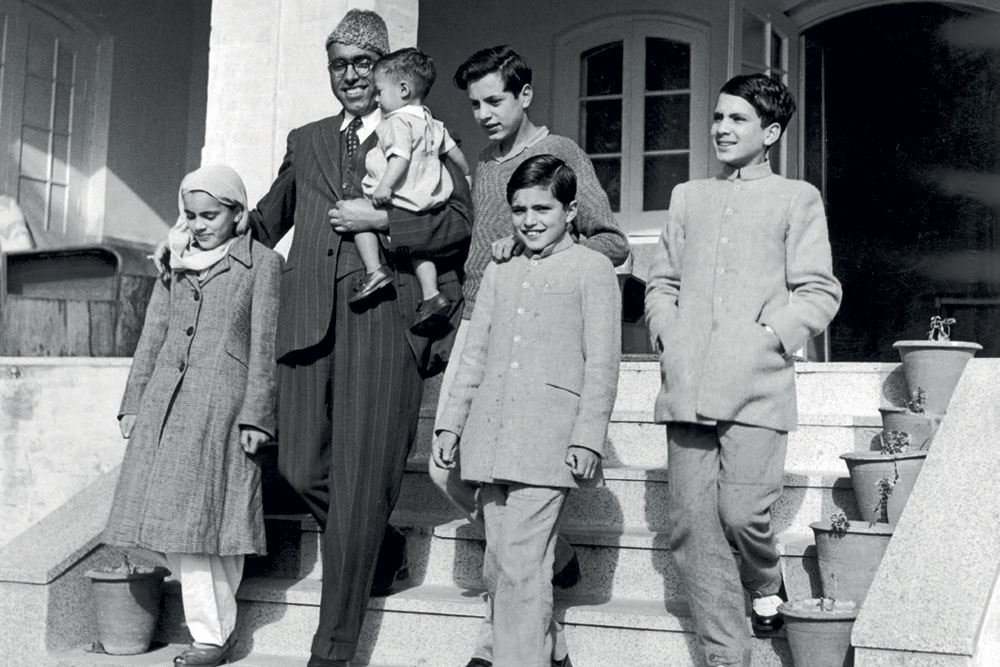

Sheikh Abdullah is often revered among a section of historians as the man who made the accession of Kashmir to the Indian Union possible, but his early anti-Dogra stance and his association with Islamist organisations make him a controversial figure. Nehru invited the wrath of nationalists for enabling the rise of this leader and his family in Indian politics. National Conference (NC), the party he founded in 1939, was earlier called All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference. It was created by Sheikh Abdullah and Chaudhry Ghulam Abbas in 1932. Although NC backed the accession of the princely state to India in 1947, Abdullah and Nehru were criticised for delaying the process. This was due to Nehru’s insistence on installing Abdullah at the helm of things. Maharaja Hari Singh, then ruler of Jammu & Kashmir, finally agreed although Abdullah had earlier raised inflammatory slogans against Singh and his clan.

Sheikh Abdullah became the prime minister of Jammu & Kashmir after the region’s accession to India and he stayed in the post until 1953 when he was dismissed, following which he accused Nehru of plotting against him. A decade or so later, he made peace with Congress’ first family and ensured that his dynasty—of the Abdullahs—enjoyed the fruits of power over the next decades. On the death of Sheikh Abdullah in 1982, his son Farooq Abdullah became chief minister of the state, occupying the post thrice, first from 1982 to 1984, then from 1986 to 1990 and finally from 1996 to 2002. His son Omar Abdullah, too, was chief minister from 2009 to 2015. Both had occupied key positions in various Union governments as ministers as well, whether in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government or the Manmohan Singh-led UPA dispensation.

But currently, with the rules of engagement changing rapidly, especially following the revocation of Article 370 that bestowed special powers on Jammu & Kashmir, the Abdullah dynasty has lost its sting and has diminished in appeal.

Sharad Pawar came to the limelight thanks to the mentorship of Maharashtra strongman YB Chavan who backed the young Pawar to contest Assembly elections in 1967. Others had objected, but Chavan endorsed Pawar’s candidature. Since then, Pawar has not left legislative politics. He was only 38 when he became chief minister of Maharashtra. His political rise was nothing short of meteoric, helping him create a solid network among corporations over the decades. In 1991, after the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, Pawar staked his claim to be prime minister, losing out to PV Narasimha Rao later. He thrived thanks to media coverage over time, and he was not ready to settle for the second slot. In 1999, he and a few Congress leaders floated the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) after he and his comrades were expelled from Congress for demanding that an Indian native must become prime minister. And despite the anti-Sonia Gandhi posturing, Pawar had no qualms about joining hands with Congress and the UPA government. The Maratha heavyweight, who had occupied several crucial berths as Union minister, positions in cricket bodies, and had been chief minister of Maharashtra in periods the state had seen violence and turmoil, soon began to promote his daughter Supriya Sule, although much of the hard work for the party was being done by his nephew Ajit Pawar.

Maratha heavyweight Sharad Pawar has been promoting his daughter Supriya Sule, although much of the hard work for the party was being done by his nephew Ajit. It is Pawar’s love for his daughter over his nephew that brought him to a point of crisis and of no return

It is Pawar’s love for his daughter over his nephew that brought him to a point of crisis and of no return. Ajit Pawar could take the slight no longer and snapped ties with his uncle last year, laid claim to the NCP party name, and joined hands with BJP to become deputy chief minister of Maharashtra. He had served as a parliamentarian and as opposition leader in the Maharashtra Assembly earlier.

Recently, Ajit Pawar said that he should have parted ways with his uncle in 2004 itself when NCP gave up its claim to the chief minister’s post while forming a government in the state in alliance with Congress. The nephew also said recently that because he is not the son of Pawar, he had lost out on a lot of political opportunities.

In this year’s election, Ajit’s wife Sunetra Pawar is pitted against sitting MP and cousin Supriya Sule of NCP (Sharad Pawar) in the Baramati constituency. The Baramati seat, as of now, is dominated by NCP owing allegiance to Ajit Pawar—whose strength gets amplified thanks to BJP’s electoral prowess—much to the disadvantage of Pawar Sr and daughter. For the 83-year-old politician, now a pale shadow of what he was as a Congress leader, nothing can be more heartbreaking than a setback for his daughter, who, again, is hoping against hope. Confronting the demons has never been this intense for the father, considered a man for all seasons to date.

At the end, the prospects for certain dynasts look bleak.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande