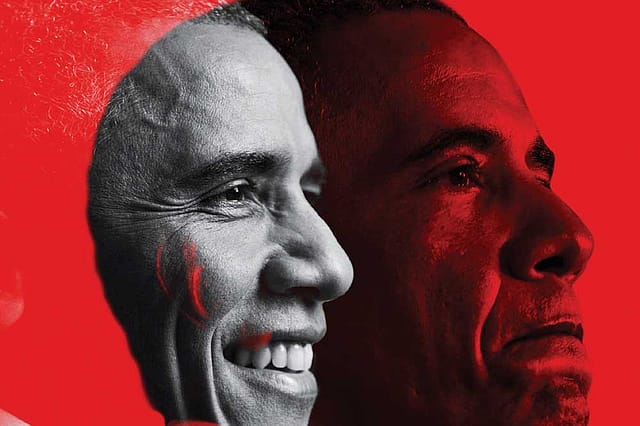

The Triumph and Tragedy of Obama

IN THE BEGINNING was the poetry, and the dreams of a people soared with its cadence. It was a time when one man's biography, an infusion of distant worlds and cultures, became an entire nation's destiny. Every word he spoke broke the frozen cynicism of political tribalism; he turned the oldest clichés of the trade into catchphrases of redemption. Suddenly, 'change' was the most original idea delivered by a freshman senator who dared to reimagine America, not as a colour-coded land of political and racial divisions, but as a unifying ideal. The context of war and imperial morality added to the urgency of his text of moderation. The wages of partisan politics had corrupted the soul of America, and it was for him to restore the frayed dreams of the founders—or that much loftier was his vision. In revolutionary fervour, they, cutting across demographics, chanted "Yes, You Can." In a rare outbreak of emotionalism, he became a nation's utmost intimacy and inspiration, a catalyst for the humanisation of politics. He promised to be the Unifier-in-Chief, and not just America, the whole free world needed one. The dawn of Barack Obama was America's repentance in retrospect, a future made fabulous by bad memories.

That was a distant yesterday, a cathartic pause in the twenty-first century's first polarising decade, when America elected its first Black president.

Eight years on, as President Obama leaves the White House, the most contested word after 'Trump' is 'legacy.' In his first inaugural address, he spoke to rapturous applause: "On this day, we gather because we have chosen hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord. On this day, we come to proclaim an end to the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn-out dogmas that for far too long strangled our politics…The time has come to reaffirm our enduring spirit; to choose our better history; to carry forward that precious gift, that noble idea passed on from generation to generation: the God-given promise that all are equal, all are free, and all deserve a chance to pursue their full measure of happiness." Poetry is out of place in today's America, an angrier, resentful, divided place where hope is not an audacity but an adventure. This is not the place he promised as a candidate: there is no red America and there is no blue America but only the United States of America. The America he leaves behind is starker in colour consciousness, and its divisions—along class, culture and race—are deeper.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

This America is not the one he addressed twelve years ago at the Democratic National Convention in Boston. That was his original inauguration, when his biography was his mandate. "My father was a foreign student, born and raised in a small village in Kenya," he told them, and his audience was not used to such storytellers with a dash of cultural otherness. "He grew up herding goats, went to school in a tin-roof shack. His father—my grandfather—was a cook, a domestic servant to the British." He told them about how his father met his mother, "born in a town on the other side of the world, in Kansas". His parents "shared an abiding faith in the possibilities of this nation". They gave him an African name, Barack, or blessed, "believing that in a tolerant America your name is no barrier to success". In America, he told his audience, "you don't have to be rich to achieve your potential." How his America has changed— "you are the change"—in twelve years. There is a feeling of déjà vu even about irony in the America that Obama has handed over to Donald Trump, perhaps the richest man ever to come stay in the White House. The new billionaire president is there because money, not fairy tale, alone can buy the biggest American Dream. Obama's poetry of reconciliation, and his own ancestral story of cultural multiplicities, is too remote to be real in the America that has rejected everything that the 'blessed' president symbolised. Maybe he floated in sublime detachment above politics-as-usual to see the churning beneath, the groundswell of resentment against all kinds of elitism. The poor against the rich. The White against the Black. The nativist against the immigrant. The working class against the bloated class. The outsider against the Establishmentarian. The nationalist against the globalist. The eight years of the great centrist saw the centre shrinking, and an exclusivist, extreme sense of Americanism taking over. He preferred the pulpit to the arena, the loftiness of a sermon to the ordinariness of a conversation, and it was quite natural that such a man was unaware of the raw passions of an unequal America erupting beyond his gaze. Even though he wanted the best of politics, politics as a craft bored him, demeaned him. So in Obama merged the elegance of an intellectual and the arrogance of an elitist. As a self-conscious socialist and welfare evangelist, he brought stability to the marketplace, but the social base was falling apart. His domestic legacy project, Obamacare, even as it came as a relief to millions of Americans, did not become a unifying reform; it sharpened the class war. He should have been the ideal healer of a broken America; instead, he became its presiding deity. How did such a good man, armed with words and phrases tailor-made for every occasion, create the mood for Trump's entry? Could there be anything more heartbreaking than this?

We could not have missed the tinge of sadness in his farewell speech—or in his last press conference in the White House. He may not have said it in so many words, but the disillusion of the man who wanted to be the reconciler-in-chief was there in every word he spoke in his final days as President. His decency would not have allowed him to name his successor as a repudiator of his legacy. He named and shamed Trump during the campaign, and once humiliated by history, Obama did not abandon his legendary cool. From an accusation, Trump became an allusion in his speeches. He was, in his eight years as president, more an existential hero than a Beltway gladiator, his tentativeness a mark of his thoughtfulness. The more he withdrew from the arena, his contempt for the political class never hidden, the more he got entrapped in his own philosophical aloofness. Whenever he intervened to make a difference, healthcare being a good example, ideology came to the fore. It was as if eight years were not enough for him to bring his conversation with power to a conclusion.

Not just America, the world too defied his poetry. Once in power, his first major speech was his address to the Muslim world from Cairo. Playing the reconciler to poetic perfection, he envisioned an America in harmony with Islam. That was a daring, and redeeming, dream to sell in the post-9/11 world. He ended the speech quoting from the Qur'an, the Talmud, and the Bible, and each quote a call for oneness. Today it is not Cuba or Iran that speaks of Obama's foreign policy legacy. It is the sword-wielding executioner in the Islamic State who brings out the moral failure of the Obama years. He was not there whenever young freedom fighters of the Middle East wanted moral as well as physical support. The world missed America, and even Israel felt orphaned. It was Obama's Lax Americana at play.

What remains—and it is a huge triumph—is the idea of the man himself: grace in the time of bitterness, good taste in the time of political vulgarity, culture in the time of crassness. Perhaps Barack Obama preferred to read a good novel when politics required him to read the mind of America.