Dreams From Obama

The epiphany came during that flight back home from the 2000 Democratic National Convention in L.A. Barack Obama went there with a friend who thought that the trip would cheer him up after his disastrous performance in the contest for Congress. The accusation by the rival campaign still resonated in his head: “Obama’s an outsider; he’s backed by white folks; he’s a Harvard elitist. And that name—is he even Black?” At the Convention, it was further humiliation. When he landed at the airport, he couldn’t rent a car because he had crossed the credit limit of his Amex card. He was denied access to the convention floor; his friend couldn’t even get him into a party that night. Next day he left for home as Al Gore was accepting the nomination. On that flight, he, almost 40 and broke and his marriage already strained, realised that perhaps the whole thing was an existential error. It just dawned on him that in running for a House seat “I had been driven not by some selfless dream of changing the world, but rather by the need to justify the choices I had already made, or to satisfy my ego, or to quell my envy of those who had achieved what I had not.” He had become what he had resisted all along as a young idealist. “I had become a politician—and not a very good one at that.”

What he doesn’t say is that a political life born in rejection and otherness will become an American catharsis. It was always there: biography as a reminder and responsibility, and in his case the exoticism of it constantly set him apart in his journeys. The first journey was recorded 25 years ago, when he published his memoirs at the age of 34. Dreams from My Father was a quest, both physical and internal, for an absence that overwhelmed his life as a young man shaped by many worlds, many colours. He was 21 and a loner by choice in New York when his aunt called from Nairobi to tell him that his father, a Kenyan, was dead. He “sat down on the couch, smelling eggs burn in the kitchen, staring at cracks in the plaster, trying to measure my loss.” His father left him when he was a two-year-old in Hawaii. Father grew within him as a story, a myth, a photograph. “That my father looked nothing like the people around me—that he was black as pitch, my mother white as milk—barely registered in my mind.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

It wouldn’t be long before inheritance became the meaning of his journeys. There were painful revelations along the way. One such moment came in Indonesia, the country of his stepfather, when he was waiting for his mother in the library of the American embassy. In one of the most poignant passages in Dreams, the boy would be transfixed by a photograph in Life magazine of a man walking down the road. On the next page, he noticed something unusual in the close-up of the man’s hands. “They had a strange, unnatural pallor, as if blood had been drawn from the flesh. Turning back to the first picture, I now saw that the man’s crinkly hair, his heavy lips and broad, fleshy nose, all had this same uneven, ghostly hue.” The accompanying article would reveal that the man, a Black who wanted to be white, was the victim of a chemical treatment. Colour was not just identity. It was a struggle. And the man was not alone in chasing, in vain, white happiness.

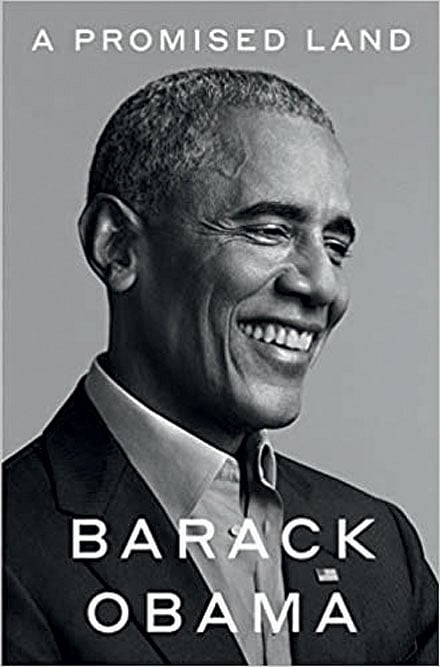

Obama’s life, as a boy brought up by a single mom and his grandparents, as a young man powered by idealism and ambition, as a tentative politician with a deeper sense of community, as a presidential candidate who ignited the post-racial imagination of America, and as America’s first Black president who put caution over the poetic spontaneity that marked his historic campaign, too, was a struggle, true, but it was the chemistry of empathy and intelligence that made him what he had become. History is still rereading his story that first reached us as an exclamation, and grew in the conscience of a country that dared to shed its own bad memories by electing him president. He is one of those writers who believe that their stories are better told by themselves, and Dreams, written with the flair of a novelist and the insight of a cultural historian, was his first attempt. It still retains its innocence, untouched by the restraints of power. A Promised Land (Viking, 768 pages, Rs 1,999), the first volume of his new memoir and the publishing event of the year, is written by someone who knows that every sentence of his is first edited by history. Its controlled elegance is the result of the distance he never fails to maintain between the story and the storyteller. Obama looks back with the modulated gaze of an outsider, and I’m sure you have noticed, this is one of those memoirs named after a place, not a person. America First, on a very personal note.

And it’s the pre-presidential passages that break the narrative barrier of distant storytelling. They are vintage Obama, written by the author of Dreams. Here we see the progression of a conflicted person, but mostly sure of his route in the maze of class and race, always aware of his mixed inheritance: “I was from everywhere and nowhere at once, a combination of ill-fitting parts, like a platypus or some imaginary beast, confined to a fragile habitat, unsure of where I belonged.” He was “a Don Quixote with no Sancho Panza.” What kept him going was a moral system, shaped by his mother, a free spirit, and the “pride in being American.” One day, he would fly to New York to see his mother, now a cancer patient, and watch with a brave face her sucking on ice cubes. Later, he would cry alone in his hotel room. Dreams from his father kicked off his journey back to his genetic and cultural inheritance. Love from his mother fortified his sense of independence and moral correctness. The companionship of Michelle, whose name he cannot invoke without the adjective “beautiful”, prepared him to build his ambition on reality. When he talked about wanting to be in politics but not part of it, she would reply: “The world as it is and the world as it should be.”

The political began to soar when he turned his moral inheritance into a theme song for change. His election strategist, David Axelrod, came up with the slogan that would outlive Obama’s campaign for the Senate seat from Illinois: Yes We Can. His stardom on the stump would earn him the prime speaker’s slot at the 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston. He had come a long way from the humiliation of 2000 in L.A. His one-time spiritual guru and an angry apostle of Black Nationalism, Jeremiah Wright, would provide the catchline of his speech: The audacity of hope. He began nervously. “But there comes a point in the speech where I find my cadence. The crowd quiets rather than roars. It’s the kind of moment I’d come to recognise in subsequent years, on certain magic nights.” The magic would sway the mind of America. Obama became the national sensation of O!bama. Four years later, the magic would take him to the White House, with a mandate to become America’s first post-racial president of reconciliation. Did he become one? Memoirs don’t answer such questions. History has not made up its mind either.

The detachment of the philosopher king becomes more pronounced in the presidential passages. The prosody of Candidate Obama gives way to the cautious prose of President Obama. Occasionally the poetic steps in to lift the narrative from the solidity of statecraft. The play of the light that cameras miss in the Oval Office, for instance: “The room is awash in light. On clear days, it pours through the huge windows on its eastern and southern ends, painting every object with a golden sheen that turns fine-grained, then dappled, as the late-afternoon sun recedes.” He spent most of his eight years of presidency in that room, and sometimes “I’d fantasize about walking out the east door and down the driveway, pass the guardhouse and wrought-iron gates, to lose myself in crowded streets and re-enter the life I’d once known.” Otherwise, it’s linear storytelling, a smooth passage through the events that defined his first term—from the crash of 2008 to the short-lived Arab Spring to the phoney war of Iraq to the just war of Afghanistan to the assassination of Osama bin Laden, the episode that brings the first volume to a resounding finale. In between, there are summitries and encounters, pen portraits and family vignettes, and the narrative tone, throughout, is that of someone who has the verbal and emotional agility to step aside from his own story for the sake of dignity and distance.

The personal sketches are sharp and brief. He is always the clever one in the room, and he makes no effort to let others notice. It’s felt nevertheless, the so-called Obama cool. Here are some sketches that stand out. Biden: “Most of all, Joe had heart. He’d overcome a bad stutter as a child (which probably explained his vigorous attachment to words) and two brain aneurysms in middle age. In politics, he’d known early success and suffered embarrassing defeats.” Manmohan Singh: “A gentle, soft-spoken economist in his seventies, with a white beard and a turban that were the marks of his Sikh faith but to the Western eye lent him the air of a holy man.” Merkel: Her “eyes were big and bright blue and could be touched by turns with frustration, amusement, or hints of sorrow.” Sarkozy: “With his dark, expressive, vaguely Mediterranean features…and a small stature…he looked like a figure out of a Toulouse-Lautrec painting.” Putin: “I noticed a casualness to his movements, a practised disinterest in his voice that indicated someone accustomed to being surrounded by subordinates and supplicants.” Family dog Bo: “…what someone once described as the only reliable friend a politician can have in Washington.”

Indian readers will be titillated by a set piece featuring Manmohan, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul. The occasion was the dinner hosted by Prime Minister Singh at his residence for the Obamas during their first India visit in November 2010. At the dinner table, Sonia was “a striking woman in her sixties, dressed in a traditional sari, with dark, probing eyes and a quiet, regal presence.” She “listened more than she spoke, careful to defer to Singh when policy matters came up, and often steered the conversation toward her son,” who had “a nervous, unformed quality about him.” The Obamas said their goodbyes when they noticed the prime minister

fighting off sleep.

The promised land of Obama is also home to subterranean suspicions, and being a serious reader of the context in which he plays out his text, he never misses the insult, the innuendo, and the demands on him to prove his patriotism, and even his citizenship. The so-called birtherism, peddled by Donald Trump, was a sinister campaign against his very being as a child and beneficiary of the promised land of America. The land is a hurt and a reward, and maybe that’s how it should be for an American who carries within him the sighs and joys of other cultures. He still retains his exoticism. In his own way, he has made otherness American again and again. As a candidate, it was pure romance. As president, it was greatness half realised.

As a writer, he has rebuilt the home that made him, and occasionally wounded him.

A writer-politician—a Gandhi, a Nehru, a Churchill, a Havel—changes the aesthetics of politics from the kitschy to the dignified. The cool dignity of Obama’s politics pervades his words, and that’s no mean achievement in an era when memoirs are tweets from hell.