The Power of My Vote Bank

From the sleepy villages to the bustling towns of western Uttar Pradesh, voters say they will reward the Modi dispensation for its generous schemes and state Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath for strict policing

/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/MyVoteBank1.jpg)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath campaigning in Ghaziabad, April 6, 2024 (Photo: AP)

HIS BODY LANGUAGE suggests that Sanjeev Balyan, Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) candidate and sitting member of Parliament (MP) from Muzaffarnagar, western Uttar Pradesh, is a man in a tearing hurry. But he still listens to my queries carefully while massaging his broad moustache. “Looks like there is no fight this time round in western Uttar Pradesh against BJP, but I still have to meet my people,” the two-time lawmaker declares.

He goes on to emphasise the significance of his party’s tie-up with Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) led by Jayant Singh Chaudhary whose father, the late Ajit Singh, he had trounced in the last General Election five years ago. RLD was part of the grand alliance of two hefty regional players in the General Election of 2019, the Akhilesh Yadav-led Samajwadi Party (SP) and Mayawati-steered Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) whose electoral performance vastly trailed expectations and forecasts based on simplistic caste arithmetic, winning a mere 15 seats. “I must go,” Balyan politely excuses himself as he climbs onto his SUV. The clean-shaven, 51-year-old Union minister dressed in sparkling white desi attire points me towards his friend Naveen Kohad who he says will brief me about his campaign. It highlights his achievements in this seat and the grander feats of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and state Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath. “We are seeking votes based on the work done,” says the politician whose energy seems contagious. Then, his convoy is gone into the searing heat of the day.

Seated comfortably in a chair on the covered veranda of Balyan’s home in the tony A2Z society of the city teeming with party workers and hangers-on, Kohad tells me that the BJP candidate visits some 10-12 localities of his constituency per day, starting off at 10AM and returning only late in the night. “He is always with the people,” he says. He dismisses the threat from the Thakur community, some of whom feel slighted about a person from the community not being given a BJP ticket this time round from this Lok Sabha constituency. “A lot of people are talking about it, but it is a demand by only a small section of the community. The majority are supportive of Balyan,” Kohad argues. He repeats the common refrain from the region in this election: people here will use their vote this election to thank Modi and Yogi for what they have done for them.

Western Uttar Pradesh, covering the Lok Sabha seats of Muzaffarnagar, Saharanpur, Kairana, Bijnor, Nagina, Moradabad, Rampur, Baghpat, Meerut, Amroha, Bulandshahr, Aligarh, Mathura, Ghaziabad, Gautam Buddh Nagar and Pilibhit, goes to the polls in the first two phases of the seven-phased General Election in which Modi is seeking a third straight term in office after previous emphatic wins in 2014 and 2019. Across this region, you often meet people who provide clarity about why they would vote for BJP—Modi’s schemes made their lives better and Yogi’s governance got rid of goondagiri (hooliganism) in the region as well as the state, the most populous one in the country. Uttar Pradesh accounts for 80 of 543 seats in Parliament and those from western Uttar Pradesh are crucial to ensuring BJP’s target for a massive majority in Lok Sabha. The ruling party, which had lost some seven seats in the region last time, is looking to improve its coalition tally of 64 to meet its ambitious target of 400-plus seats in the Lower House of Parliament.

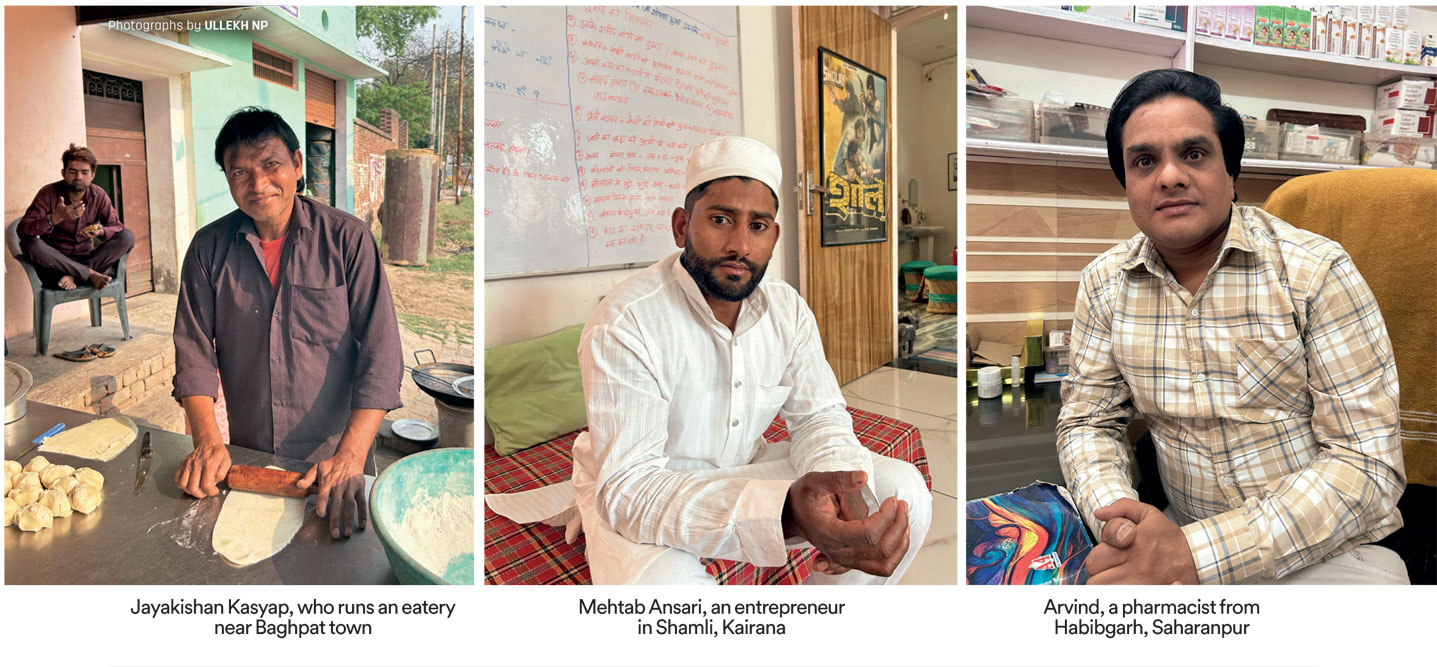

Jayakishan Kasyap, who runs a roadside eatery in a village near Baghpat town, is busy making traditional Indian bread for his customers. He says his business is good although the pomp and grandeur of usual election campaigns are missing this year. “Maybe it is the heat, but then elections often take place round this time of the year when the weather is scorching,” he makes a statement, and then hastens to correct himself. “Maybe the opposition is not excited enough.” But none of it worries him one bit, he asserts, as he spiritedly places balls of rolled dough on a tray to make rotis later. He takes a break to serve me tea, which is sweeter than I had anticipated. “The overall atmosphere is good,” he avers and then laughs off the question about which party he would vote for. Without naming BJP, he tells me that his vote is for the party that helped him build a home and improved the law-and-order situation in his neighbourhood. He guffaws after making what was a pithy statement as though it was a stock reply. Then his facial expression turns grave. Although he is worried about the high cost of living and fewer employment opportunities for his 20-year-old son who is now working as a mason, he expects that “good policies will usher in good times”.

RLD founder, the late Ajit Singh, had represented the Baghpat Lok Sabha seat in 1999, 2004 and 2009, winning a hat-trick. His father, the legendary Chaudhary Charan Singh, the former prime minister who was recently awarded the highest civilian honour in India, Bharat Ratna, had represented this constituency in Parliament in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. In this historically significant seat, Satyapal Singh of BJP trounced Ajit Singh in 2014 and his son Jayant Chaudhary in 2019. This time, the seat has gone to RLD thanks to an alliance sealed in March. The key candidates in the fray in this election are RLD’s Raj Kumar Sagwan, SP’s Amarpal Sharma and BSP’s Praveen Bansal.

Uttar Pradesh accounts for 80 of 543 seats in parliament and those from western Uttar Pradesh are crucial to ensuring BJP’s target for a massive majority in Lok Sabha

I RUN INTO a group of people discussing politics right in the heart of Baghpat town—not far from the office of the municipal corporation—where a farmer, Rohthash Singh, who is in his 50s, is telling a younger man, Sagar Ruhela, that if he doesn’t get jobs even after acquiring specialised skills, he should be bold enough to become an entrepreneur. “I tell him we are getting the benefits of Central schemes and a peaceful state under Yogi, and so he should not wait for government jobs, but look for avenues to avail of loans and start a business on his own,” Singh says. But Ruhela isn’t convinced yet. Singh goes on to argue forcefully about why it doesn’t matter who is the candidate from Baghpat so long as the person’s victory ensures the continuation of the Modi dispensation. “Problems of the poor won’t disappear in one stroke. It will take time,” he reasons, using mild expletives against those in the group who bring up inflation. The others are not against BJP or the projection of the Modi-Yogi combo as a winning formula, but they are hit by the rise in prices of essential goods, including vegetables.

Their arguments aren’t unfounded: India’s wholesale price index-based inflation accelerated to 0.53 per cent in March on an annual basis, its highest level in three months, as against 0.20 per cent in February, says data from the Union Commerce Ministry. Similarly, official numbers show that the unemployment rate in the country rose to 5.4 per cent in 2022-23 from 4.9 per cent in 2013-14. Reports quoting official data suggest that as many as 16 per cent of urban youth in the age group of 15-29 years remained unemployed in 2022-23 owing to multiple reasons, ranging from poor skills to a lack of quality jobs. Not surprisingly, a Lokniti-CSDS survey showed that, in this election, unemployment is the primary concern of 27 per cent of the 10,000 voters across 19 of India’s 28 states; inflation came second at 23 per cent, according to reports.

The mood among BJP leaders in western Uttar Pradesh is upbeat because they argue that poll momentum is on their side and that the overall trend is for all to see: that the performance of the Centre and the state is what finally counts, as evident from the narrative that has captured people’s imagination in the region. They are not off the mark, as the responses of voters confirm, and therefore party leaders aren’t overly concerned about common people voicing their worries and woes as well. Once BJP is voted to power again, the party-led government will work towards addressing all such issues, goes the commonly held belief here.

After all, Rome was not built in a day, a party leader in Delhi tells me. “We will solve more problems, going ahead, than we have done before,” he professes, adding that there is a breath of fresh air in the country. “This is a new beginning,” he says, leaving no room for doubt or confusion about the triumphant mood in the BJP camp at a time when the opposition, especially Congress, is in disarray and regional parties unable to ally cohesively enough to take on the might of BJP and allies.

BJP is also buoyed by the backing it is getting from the Muslims, and how they are winning from seats in western Uttar Pradesh that have a huge population of Muslims, on an average, of close to 30 per cent. In some of them, Muslims account for as high as 40-50 per cent of the population.

Kairana is one such constituency.

Mehtab Ansari, an entrepreneur based in Shamli, which falls in the Kairana seat, says it is his personal experience that for all the cries of Hindutva that the ruling party and its leaders make, as a government, the Centre doesn’t discriminate against anyone while disbursing welfare schemes. As a lower-class Muslim, Ansari feels that bullying by Gujjar Muslims and other land-owning communities has fallen drastically under Yogi. Ansari is a landscape artist who has done various projects in Delhi, including for the G20 summit, various government offices and at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. “We are a team of people who accept work across cities in India, including metropolises,” he says, emphasising that, back home, discrimination from land-owning communities among the Muslims was extreme until the Yogi government began to show them their place—which means ending their goondagiri, which he says they have a special talent for. Revati Laul, author and director at Sarfaroshi Foundation in Shamli, which works among Hindu and Muslim communities, agrees that the relationships between the formerly landowning communities and the formerly have-nots who are now upwardly mobile are complicated. Which explains why backward-class Muslims tend to gravitate towards BJP, she says.

This writer met many such groups of Muslims across the region, who talk typically like Hindu voters, attesting that their lives have improved thanks to Central schemes and strict policing under Yogi. “In this election, there is not much of Hindu-Muslim rivalry and hostilities. Whatever BJP has done in terms of temple building, etc., does not worry us much so long as we are not subject to bhed bhav [discrimination] in the allotment of welfare policies,” says Zeeshan, also from Shamli, who says he belongs to the Pasmanda community, an umbrella term for OBC and Dalit Muslims. In the 2014 Lok Sabha election, BJP had won in Muslim-dominated seats of the region, including Rampur, Amroha, Muzaffarnagar, Saharanpur, Moradabad, Bijnor and Nagina, all of which were once upon a time strongholds of the Samajwadi Party (SP) and Congress. In the last election of 2019, the SP-Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)-RLD alliance won 15 seats in Uttar Pradesh, a good chunk of them from this region. This time round, Muslim votes are likely to get split.

Many in Shamli attest that as a government, the centre doesn’t discriminate against anyone while disbursing welfare schemes and that regardless of anyone’s religion, their lives have improved

The Kairana constituency is dominated by Muslims who are said to make up 5.5 lakh of the total close to 18 lakh electorate. In2014, Hukum Singh of BJP had wrested this seat from BSP, which had won in 2009. Although RLD, which was then in the anti-BJP camp, won the seat in the by-poll held in 2018 after the demise of Singh, Pradeep Choudhary of BJP won it back in the 2019 election. This time, 55-year-old Choudhary, the BJP candidate and incumbent, is up against SP’s Iqra Hasan and BSP’s Shripal Rana. At 27, London-educated Iqra Hasan is one of the youngest candidates in the polls and is the daughter of politicians, the late Munawwar Hasan and Tabassum Hasan, both former MPs from Kairana, famous for the Kirana gharana of Hindustani classical music that has produced the likes of Pandit Bhimsen Joshi.

“Jo kaam karega unko vote milega (those who work will get votes),” says Saira from the Saharanpur Lok Sabha constituency, who says her family is content that the law and order situation has improved all over the state, not just in this seat. “They are not worried the way they used to be about us kids before,” says this medical student. No different is the sentiment from Arvind, who runs a pharmacy and also checks the blood pressure of people for a fee and lives in the densely Dalit-populated Habibgarh area of Saharanpur. The common refrain here is that “goondagiri has ended”. He thinks that there is hardly any anti-incumbency sentiment against the ruling BJP in his hometown. In Saharanpur, the key candidates are BSP’s Majid Ali, former lawmaker and BJP leader Raghav Lakhanpal, and Congress’ Imran Masood.

But there are a few others who are worried about the Hindu nationalist surge that they say may not be good for “us” in the long run. Fareed Khan, who lives in Jhatav Nagar in the city, says that development and federal schemes are indications of good governance, but BJP workers at the grassroots tend to be aggressive. “They are not very nice people,” he says laughing. BSP had won this seat last time but Haji Fazlur Rehman, the MP, is not contesting this time round. Roshan Lal, who depends on his children now that he is in his 70s, repeats what you tend to hear from a large chunk of voters in the region as if it is the theme of the election: “Welfare schemes have helped us a lot in building our home, toilets.” Lal adds that the Ayushman Bharat card, which people here describe as the “Modi card”, is the backbone of his life because he can avail of free treatment for up to ₹5 lakh for his health problems. Some others, meanwhile, speak from their experience that the Ayushman Bharat card is not accepted in many hospitals, arguing that it is not as useful as it is made to appear.

MEANWHILE, IN MUZAFFARNAGAR, as stated before, a section of voters from the Thakur community aren’t immensely pleased with what they call “lack of due representation”. Deepak Pundir, a small-time trader in his forties, is crestfallen and says that “some people in the party are obsessed with promoting people only from their caste”, referring to the Jat community. On the other hand, for Atul Verma of Naugawan Sadat, Amroha Lok Sabha constituency, the candidate that BJP fields is not as important as the party itself. “I will vote for whoever the party names, especially because candidates seldom rise to your expectations. What I am looking for is to strengthen the hands of Modi at the Centre and Yogi here in the state,” he tells me. In this seat, one of the crucial ones in the region, Kanwar Singh Tanwar, who was MP from 2014 to 2019, is the candidate for BJP against sitting MP Kunwar Danish Ali of Congress, who had won last time on a BSP ticket. BSP, for its part, has fielded Mujahid Hussain in this election. Devendra Nagpal of RLD had won this seat back in 2009.

Rampur was once synonymous with SP founding member and strongman Azam Khan who is now languishing in Sitapur jail. The former 10-time MLA from Rampur, his wife Tanzeen Fatima and son Abdullah Azam Khan are behind bars for illegally acquiring a fake birth certificate (for the son), in a case filed by local BJP leader Akash Saxena. Although the 75-year-old Khan, a former high-profile minister in Uttar Pradesh, is flexing his political muscles to get his people to contest polls in at least some seats, his influence within the party and the constituency seems to be on the wane. A section of Khan’s supporters, one of whom is a restaurateur in the town, is not happy with SP chief Akhilesh Yadav for not being “accommodative enough”. At the same time, he is also upset with BJP for what they call a “witch hunt” on their leader. But among the common folk here, sentiments are vastly different. Naresh Kumar Saini, a shopkeeper from the Awas Vikas area in Rampur, is glad that the “rowdyism” of the Azam Khan era is now a thing of the past since he is in jail. He, however, states that a lot more needs to be done to bring more industrial units to the city to address unemployment woes. In this seat, in 2019, Azam Khan had defeated BJP’s Jaya Prada, but in the by-poll held in 2022, Ghanshyam Singh Lodhi of BJP—who was earlier a protégé of Azam Khan—had won against SP’s Mohammad Asim Raza.

This time, Khan wanted Akhilesh Yadav to contest the polls from here, but the latter refused to do so. Then, much to the anguish of Khan and his men, nomination papers of Khan’s close aides, Asim Raza and Abdul Salam, were rejected over not supplying all the details required. On the contrary, SP fielded Muhibullah Nadwi, an imam of a mosque in Delhi’s Parliament Street, a candidature that Khan and his team disapprove of. While they are dismayed by this decision by the SP leadership, what adds to the woes of non-BJP parties in this seat, which accounts for close to 50 per cent Muslim voters, is the potential split in minority votes between SP and BSP’s Zeeshan Khan.

Amidst all this confusion, Khan somehow managed to get his nominee Ruchi Veera made the SP candidate from Moradabad, replacing sitting lawmaker ST Hasan. Moradabad is one of the Lok Sabha seats in the state that has a Muslim majority. Hasan had won Moradabad in 2019 by defeating BJP’s Kunwar Sarvesh Kumar Singh. Singh had defeated Hasan in 2014.

In Rampur, people say that the ‘rowdyism’ of the Azam Khan era is now a thing of the past since he is in jail, but state that a lot more needs to be done to bring new industrial units to the city to address unemployment woes

A section of voters in the region aren’t thrilled at the prospect of what looks like a unilateral election, with BJP enjoying a big lead. Hansa Makhijani Jain, a Meerut-based author, tells me that she relishes more choices. “I want more opposition. Now, only positive issues are highlighted. Day-to-day living costs are high, but very few or none are talking about it,” the 39-year-old mother of two says, conceding that it is a masterstroke on the part of BJP to pitch Arun Govil, who had acted as Lord Ram in Ramanand Sagar’s serial Ramayan. “People tend to see Ram in him,” she says. Jain also rues the demonisation of the opposition and that there is a clear polarisation, which she describes as “us and them”. At the same time, inflation is draining the middle class. Indian National Army veteran Shah Nawaz Khan, Mohsina Kidwai and others have won from this prestigious seat in the past. In the last three Lok Sabha elections, BJP had won this seat. This time, BJP’s Arun Govil will be up against candidates such as BSP’s Devvrat Kumar Tyagi and SP’s Sunita Verma.

Among other key constituencies in the region, BJP’s Hema Malini is looking for a hat-trick in Mathura. In 2019, the actress-politician defeated Kumar Narendra Singh, and Jayant Chaudhary in 2014. In Pilibhit, interestingly, we will see an election in which neither Maneka Gandhi nor her son Varun Gandhi is a candidate. Since 1996, between them, the mother and son had won from this seat. Jitin Prasada replaces Varun Gandhi as BJP’s nominee. Maneka Gandhi will seek re-election for BJP from Sultanpur.

Notwithstanding subtle undercurrents of discontent in some areas, BJP has a clear edge across the region in terms of perception. Voters feel that Congress is as good as dead, having won only one seat in the state last time. SP, for its part, was hoping to encash what it calls PDA—no, not public display of affection or the seat-sharing arrangement with Congress, but its focus on Pichda (backwards), Dalit (Scheduled Castes) and Alpsankhyak (minorities). But as SP politician and academic Sudhir Panwar admits, “BJP has mastered the art of winning elections. In terms of perception, there is no critical mass of voters on the opposition side to checkmate the ruling party. There are murmurs and noises but there are hardly any mobilisations against them.” Indeed, it would be a miracle if the opposition makes headway.

Another SP leader, who blames the Congress for being overly selfish over the years and squandering away multiple political opportunities since 2014, perhaps sums up the mood in the region: “The sentiment here is that if you are not voting for Modi, you are wasting your vote.”

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

Beware the Digital Arrest Madhavankutty Pillai

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair