The Silence of Robert Vadra

…and what it says about him and the party led by his in-laws

Jatin Gandhi

Jatin Gandhi

Jatin Gandhi

|

10 Oct, 2012

Jatin Gandhi

|

10 Oct, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/vadra.jpg)

…and what it says about him and the party led by his in-laws

Two years before he lost faith in the ‘Mango people’, Robert Vadra told The Times of India that he had been under party pressure to contest the 2009 Lok Sabha election from Sultanpur, the constituency adjoining his mother-in-law Sonia Gandhi’s Raebareli and brother-in-law Rahul Gandhi’s Amethi. “There was a huge demand for me to stand [from Sultanpur],” he told the paper, “but I was clear that it was not my place. I was being recognised only because of the family.”

Unknowingly, Vadra had gone to the heart of the matter that is now being contested in the public domain after charges of a nexus between him and DLF have been levelled by the India Against Corruption (IAC) movement reborn as a political party. What Vadra, as Priyanka Gandhi’s husband, acknowledged in 2009 is exactly what the party loyal to the family he has married into has failed to accept today. This is as true of the host of lawyers who think politics in this country is entirely a matter of what is legally tenable, and that issues of propriety or public perception do not count in a democracy.

Would it have been a crime for Robert Vadra to contest the 2009 polls? Would any court in the country have struck it down? But Vadra thought it better not to, because he was paying heed to public perception. Why, then, should the same logic of public perception not apply to his business dealings? After all, he has shown due care in the past to avoid precisely such perceptions of any business that his family might have conducted.

THE PAST

The media discovered the Vadras—a Punjabi family with business interests in Moradabad and a house in Delhi’s posh New Friends Colony—barely weeks before the wedding of Robert and Priyanka in February 1997. Bhavdeep Kang of Outlook, in a report titled ‘The groom of 1997’, pieced together information from interviews with Vadra, his friends, family and business associates back in Moradabad. Kang found Vadra ‘extremely charming, soft spoken and poised, without the slightest hint of pretension. Mr Nice Guy in person’. Among other things, she described Vadra as only ‘moderately well to do’ and not the high-flying business success that he clearly is today.

At the time of his marriage, Vadra was 28, and ran a costume jewellery export firm called Artex in Delhi, having broken away from his father Rajindra Vadra’s brass export business. The Vadheras, as they once spelt their family name, were originally from Sialkot (now in Pakistan), and had set up a brass business seven years after Partition in Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh. Back in undivided Punjab, Robert’s grandfather Hukumat Rai Vadhera ran a sports goods business, but moved to Karnataka immediately after Partition and set up Mysore Electroplating. From metal coating, the family moved into metal exports, setting up base in Moradabad, where they took the surname ‘Vadra’, and as their business did well, they got themselves a house in Delhi.

In the first edition of his book on Sonia Gandhi (the material is missing in subsequent editions), journalist Rashid Kidwai notes that five years after the Robert-Priyanka marriage, Sonia had to caution party leaders not to have anything to do with ‘close relatives of Robert Vadra’. Sonia Gandhi’s directive came after Vadra had issued a public notice severing ties with his family.

That notice, drafted by Arun Bhardwaj, son of former Law Minister Hans Raj Bhardwaj (currently Governor of Karnataka), read: ‘It has been brought to the notice of my client that some persons including Rajindra Vadra (Robert’s father, now dead) resident of C-7, Amar Colony and Richard Vadra, resident of Basant Vihar Colony, Civil Lines, Moradabad, UP, are misrepresenting to the public that they are working on behalf of my client and allegedly promising jobs and other favours in return for money. Even though Rajindra Vadra and Richard Vadra are relatives of my client they have no access to my client. Public at large is hereby put to notice that my client has not authorised Rajindra Vadra and Richard Vadra and anyone else to work for him or to use his name in any manner and make such misrepresentations to anybody. Such misrepresentations are without the knowledge and consent of my client.’

According to Kidwai, ‘Informed sources said Sonia took the step of issuing a directive to chief ministers of party ruled states, AICC functionaries and others after receiving many complaints that the Vadras (not Robert) were seeking favours using the Nehru-Gandhi family name. It was said that when Salman Khurshid was UPCC president, Robert’s brother Richard (now dead) had allegedly called him up to recommend names of some local politicians from hometown Moradabad.’

Robert’s livid father told an interviewer, “Robert himself makes calls for his friends, why can’t I make a call for a friend who can’t pay lakhs in donation for a school admission?”

In a subsequent interview, Robert claimed that his move was pre-emptive, aimed at stopping the two, especially his brother Richard, in their tracks. “When people come to me for favours, I immediately say ‘no’. I mind my own business. It’s not a large one. But it helps me make ends meet and I have a happy life. That’s what it’s all about. Now, after this advertisement, people who approach [my relatives] will stop doing so. All this will stop. It’s not just my relatives, it’s also people who think they can get to me and Priyanka. And that’s not going to happen. In the long run, this advertisement was a smart idea. It’s better to act now before anyone is hurt.”

Today, Vadra cannot make the same claims about his business. The question is not whether his business makes ends meets, or even if he leads a happy life. What matters today is his prolonged silence on charges of far greater impropriety. In a country committed in principle to its citizens’ right to information, and one long menaced by the phenomenon of power peddling, people at large have a right to know how Robert Vadra’s businesses grew so quickly once the UPA was in power.

SHAPING UP

Vadra’s marriage to Priyanka had surprised many not only because of the layers of secrecy that have surrounded the family, but also because many did not see much in common between the two. A friend of Priyanka, in Kang’s report, described Vadra as a ‘puppy.’ In the years after the marriage, while Priyanka has focused on bringing up their children, Raihan and Miraya, Vadra is said to have spent most of his time expanding his business. Priyanka’s spare time is spent on reading, meditation and Buddhism studies, while Vadra likes socialising (partying especially). Speaking to a reporter at a Page 3 event, he once gloated about how a designer friend had wanted him to walk the ramp, which he refused. In another interview, he spoke of how his gifts to Priyanka were mostly confined to books or music “because she is not into brands”. While she gravitated towards honing her cooking skills for her children, a touch picked up from her mother, Vadra took to chiselling his physique as part of a fitness regimen.

Vadra’s presence on social networking sites has an interesting tale to tell. Before he shut his Facebook account, his albums open to visitors featured pictures of him flaunting his rippling muscles. Vadra once told an interviewer that he had worked hard on his body and lost 20 kg in five years. “He ran a fitness bulletin on his FB page,” recalls a Facebook friend. Vadra would post bulletins of his physical exploits and often brag about how he was pushing the limits of fitness by doing that extra few kilometres of running or cycling. “He would take questions on fitness on his FB page,” the friend adds.

A fellow gymgoer at an elite fitness club in Delhi’s Connaught Place says Vadra comes across as a “typical Delhi businessman ready to mingle and free to chat”. Vadra himself has confessed to doling out workout advice in his interviews. He is said to be close to Rahul Gandhi, who calls him ‘Rob’, partly because the two share a passion for gruelling workouts at the gym and for superbikes.

Vadra seems to like the nickname. On Twitter, he is @Robdbob. His tweets, few and far between, have mostly ranged from the thoughts of a fitness freak to the anxieties of a father, with an occasional rant on the Dynasty’s son-in-law under a scanner for his business. ‘What the hell… Now I own Indigo airlines ?!! This rubbish just floats around and unfortunately everyone believes it ! I give up! Who cares’ he tweeted on 30 August. Sample a few more over the past six months. On 20 September: ‘Really fantastic to see the change in Delhi on Health and fitness. Each one is putting in the efforts to stay healthy. Great future!’ On Independence Day, he tweeted: ‘Recession in Europe is a farce… Ppl everywhere u go. Hotels sold out, restaurants sold out. Countries could survive on tourism !!’ This, incidentally, was a day on which Prime Minister Manmohan Singh blamed Europe’s recession among other things for India’s economic slowdown.

In 1997, Vadra would use a Maruti Gypsy to travel to office. Recently, reveals another businessman who shares his interest in superbikes and fast cars, he bought a Jaguar. The Vadra garage includes vehicles made by Mercedes, BMW and Land Rover. And he is rather fond of his 1800 cc Suzuki Intruder, a Rs 15 lakh cruise bike that he rides at least once a week—often to Delhi Golf Club—when he is in town.

Vadra is not just a fitness freak, he is an avid golfer too. The golf course seems to have played a significant role in his post-wedding evolution from Mr Nice Guy of modest means to a wealthy businessman with enviable assets.

THE CHARGES

The allegations by IAC read: ‘In the last 4 years, Robert Vadra has gone on a property buying binge and has purchased at least 31 properties mostly in and around New Delhi, which even at the time of their purchase were worth several hundred crores. An analysis of the balance sheets and audit reports of 5 companies set up by him (and owned exclusively by him and his mother) on or after 1/11/2007 show that the total share capital of these companies was just Rs 50 lakh and these companies together had no income from any legitimate business activity (except by way of interest derived from interest free loans obtained from DLF). Yet during 2007-2010 they have acquired properties which were worth well over Rs 300 crore even at their time of acquisition and are worth more than Rs 500 crore as of today.’

DLF Ltd, India’s top real estate developer, issued a statement denying the charges. ‘The business relationship of DLF with Mr Robert Vadra or his companies, has been in his capacity as an individual entrepreneur, on a completely transparent and at an arm’s length basis. Our business relationship has been conducted to the highest standards of ethics and transparency,’ stated Sanjey Roy, vice-president, corporate Communications, DLF, nearly 24 hours after IAC made its charges public at a press conference on 5 October in Delhi.

In March 2011, when The Economic Times had reported Vadra’s quiet foray into the real estate business and his association with DLF, he had told the paper, “I have known the DLF people for a long time and they are friends of mine. I had wanted to invest in real estate and one thing led to another. Right now, I can only be part of a small hotel. If I were taking favours from people I would be doing far bigger things. But I am doing this on my own. I can’t expand immediately but I hope to expand a few years down the line.”

This raises more questions than it answers. Did his friendship with ‘DLF people’ precede his becoming a Nehru-Gandhi son-in-law? Do ‘DLF people’ really like being friends with Robert Vadra or the son-in-law of Congress President Sonia Gandhi? If no favours were being done to him, how come his business has expanded so dramatically in the years that the UPA has been in power at the Centre and the Congress in Haryana (where most land deals were located)? Do Vadra and the Congress leadership not know that the very fact of a business arrangement with a Nehru-Gandhi son-in-law gives a company, especially in a sector as prone to discretionary fiat as real-estate, immense advantages?

These are fair questions, all worth asking and in need of answers, not from DLF but from Vadra, whose rebuttal (a copy of which was emailed to Open by his office) of IAC’s allegations only says that these are false and defamatory, aimed at seeking publicity for the movement’s new political outfit. In Vadra’s words, ‘My business transactions are fully reflected in financial statements filed before appropriate government authorities in compliance with the law. They are available in the public domain to anyone interested in knowing the truth.’

Indeed. According to a report in Business Standard published on 10 October, records show that Vadra’s firm Sky Light Hospitality acquired 3.5 acres of land in Manesar for Rs 15.38 crore—most of the money taken as an overdraft from Corporation Bank—that got commercial development clearance from the Haryana government in March 2008 and was soon resold to DLF for Rs 58 crore.

THE BACKGROUND

The allegations come at a time when the threat posed by crony capitalism to India’s political system is a matter of grave concern. It is what has evoked such anger over the 2G scam and Coalgate. Arbitrary awards of resources by ministers to large firms appear to have converted public money into private wealth without the people’s consent.

The Radia Tapes were a shock because they unveiled the networks that operate behind the scenes to influence government policy. Many of the big names on those tapes did nothing that would count as criminal under strict application of the law, yet the current consensus seems to be that the revelations were in the public interest. The publication of those tapes has meant that citizens are better informed of the ties and conduct of those featured, be it Vir Sanghvi and Barkha Dutt of the media, A Raja and Kanimozhi in government, or Ratan Tata in business.

Another person who figured on the tapes, Ranjan Bhattacharya, foster son-in-law of former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, may hold the key to the BJP’s muted response on the issue. Bhattacharya is heard boasting of his access to some powerful figures in business such as Mukesh (who he says told him “Ab toh Congress apni dukaan hai”) and in the UPA Government who he refers to as Ghulam and GNA, and SG (asked who SG is, he says “SG is SG boss”). It was the first time that rumours of Bhattacharya’s myriad links were backed by something in the public domain.

The day after the Vadra story was published in The Economic Times, Nishikant Dubey, a BJP MP from Jharkhand, moved a notice for the suspension of question hour in Parliament and a discussion instead on Vadra’s business. Dubey tells Open that the Speaker had ruled against the notice, and the discussion never took place, “My contention was if Ranjan Bhattacharya’s business deals could be discussed in Parliament, why not Vadra’s?”

In 2001, he says, the Speaker had allowed a discussion on the businesses of Atal Behari Vajpayee’s foster son-in-law. Dubey adds that he did not press the matter further because it was the Budget Session. In a meeting of BJP leaders in Parliament two days after the notice, party leaders were divided over embarrassing Congress President Sonia Gandhi over Vadra’s dealing without “proper verification” of the details that had surfaced. The BJP back then, which is now asking for a thorough probe into the allegations against Vadra, never pressed the matter further after Dubey’s notice was overruled.

Whatever the compulsions of a political party, the fact is that in the post-Radia era, no one’s dealings can escape public scrutiny, and no conspiracy of silence can be allowed to prevail. Even so, it is clear that the media has failed to examine Sky Light’s dealings in detail in the year since the ET report. Only now, after Arvind Kejriwal and his IAC team have raised such a stink, has the matter got the attention it deserves, contrary to what the Congress likes to believe.

LACK OF POLITICAL SENSE

Soon after IAC’s allegations, Central ministers leapt to Vadra’s defence. Salman Khurshid, in an interview to Times Now, appeared an angry Congress worker more than a man entrusted with overseeing the country’s justice apparatus. The Union Law Minister argued that if a man went to a good school and made friends, his relations were bound to fetch him favours. Such statements, like Kapil Sibal’s ‘no loss’ on the 2G scam, would make anyone wonder whether these lawyers in high positions are rallying to help the party or damage it further.

This issue is not in the courts, it is in the public space. The Congress does seem to understand the difference. A senior political journalist of a leading English news channel says that at least two ministers in the Government had called up the channel asking to be interviewed in response to the allegations against Vadra. Both went on air bending over backwards to defend Vadra’s deals as ‘clean’ and those of a ‘private’ businessman.

But the stance they and other Congress members took in public were so contradictory that they cannot survive even cursory scrutiny. A party cannot on one hand claim that Vadra’s business deals with DLF are a matter between two private entities and on the other allege that IAC is trying to malign the Congress and its president’s family.

Robert Vadra is not the first Nehru-Gandhi son-in-law to hit the public eye. Indira Gandhi’s husband Feroze too had caused his father-in-law Jawaharlal Nehru, who was PM at the time, considerable embarrassment. Ironically, for those who trace India’s crisis of crony capitalism to liberalisation, that episode involved a similar nexus between money and power, except that Feroze was the one making the accusations. Inder Malhotra, in Indira Gandhi: A Personal and Political Biography, writes of Feroze Gandhi’s maiden speech in Parliament in 1954 (he was elected to the Lok Sabha twice from Raebareli, in 1952 and 1957): ‘He pitilessly and diligently exposed the misdeeds of a business house, particularly the gross misuse of insurance funds at its disposal. This led soon enough to the nationalisation of all insurance companies and the arrest and imprisonment of the head of the business house, Ramakrishna Dalmia…Feroze was admired by an admiring public as a giant killer. He reached the peak of his glory in 1958 when he rose in Parliament to indict the Life Insurance Corporation he had helped set up….he cited the corporation’s dubious investments in the shares of questionable firms owned by an adventurer named Mundhra.’ The Mundhra deal led to Nehru’s Finance Minister and aide TT Krishnamachari resigning.

Today’s Congress seems like another party. But the country’s problems are much the same. And observers are appalled by the lack of transparency in deals being done by the wealthy under the aegis of those with power. This is why the Vadra case demands our attention. It involves money and power, and while the link may not be a legal case yet, it is being watched very carefully across the country. Whatever the law says, observers know that it is not possible to draw lines between Robert Vadra the individual, Robert Vadra the businessman and Robert Vadra the Nehru-Gandhi son-in-law.

That is the nature of politics. When Vadra issued a notice distancing himself from his family, he clearly understood this. Today, he cannot turn around and demand complete privacy.

A report in The Hindu says that the assets of his companies grew rapidly without any employees, without any clarity on what exactly, if anything, these companies were up to. Now, evidence is emerging of his partnership in a proposed DLF special economic zone. As the questions get more insistent, denial will not work. In the meantime, it is Vadra’s silence that has a lot to say.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

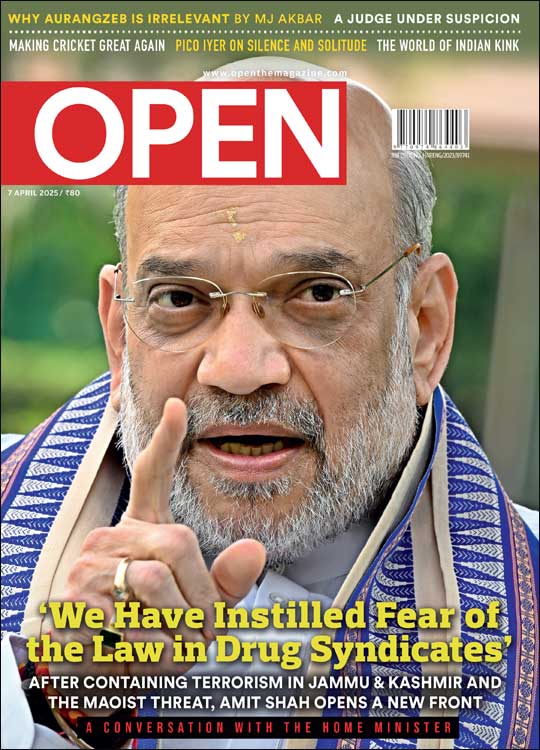

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

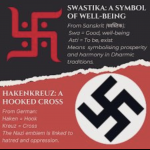

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh