Helpless in Chitapur

An Israeli journalist wonders if there is any difference at all between how Israel treats Palestinians and how India treats its poor

Recently, I moved into a lovely little rented, cement flat. Although I have sworn I would never again live under a concrete roof, I am loving it; no raindrops falling on this head this monsoon season. After many years in a crumbling, funky stone house in the jungle, the bliss of solidity is a revelation. In my old place, every time the wind blew, or a langoor loped across the roof, a shingle would shift or shatter—not so bad in the dry season, but a true disaster in the monsoon. Perhaps I had taken my worship of Mother Nature a little too far: must one really live with scorpions under the mattress, vipers in every crack, termites in every cupboard, and lizards on every wall in order to commune with She Who Gives Life To All? I think not, but it took me 10 years to reach that conclusion and discover the deeply spiritual benefits of a dry (and venom free) bed.

My housekeeper Sujata loves the new flat as well; she used to consider me crazy. "This is good, this is right," she said the first time I brought her here. She had just returned from a long holiday in her village. She always asks for two weeks, but it is never less than a month until she returns, and who can blame her? Sujata and her husband, a day labourer, stay in a room the size of a single mattress in a tenement for migrant workers. They are quite alone here in Goa, where they came to make their fortune but haven't. Back home in the village of Chitapur in the Gulbarga district of northern Karnataka, her family and in-laws adore and fuss over her. At night, on their charpais on the roof, they sleep to the soft whispers of family and neighbours from every direction. Most people here were conceived on these roofs, under the vast, twinkling sky.

2026 New Year Issue

Essays by Shashi Tharoor, Sumana Roy, Ram Madhav, Swapan Dasgupta, Carlo Pizzati, Manjari Chaturvedi, TCA Raghavan, Vinita Dawra Nangia, Rami Niranjan Desai, Shylashri Shankar, Roderick Matthews, Suvir Saran

The couple would like to buy land in Chitapur and eventually build something of their own, but as hard as they work, they can't seem to save, and that dream is starting to fade. Still, a pink or yellow hibiscus adorns her perfect ponytail every morning and her sweet shy smile lights up my lovely new flat.

Last month, while chopping onions, Sujata told me that bulldozers had come to Chitapur the day before and demolished hundreds of houses, leaving the families that had lived in them homeless. Over the rest of that day and week (during which the demolitions continued), this is what I learned from conversations with those in Chitapur: there was some vague 'masterplan' that demanded the construction of an 'ambulance road'. There had been some kind of warning several days earlier, but they had not all properly understood nor known how to stop it. There was no talk of compensation. No one was offering the families any guidance on how to get emergency assistance or relocation support. They were all terrified of 'The Madam' on the scene; when one man insisted she give clear answers on what was happening, she asked him to point to his home and then had the bulldozer demolish it immediately. One local politician I spoke to assured me, incorrectly, that only a few houses had been demolished, almost all on "encroached land". (He did not actually go there himself to see any of this with his own eyes, and did not care to discuss the 'philosophical' need of all people to live somewhere even if they are poor.) He assured me that what was happening in Chitapur was not extraordinary; it was happening all over northern Karnataka and had been sanctioned by the Supreme Court as a necessary measure to widen roads.

That did not make the distress any less alarming. Thousands of newly homeless men and women, children, babies and aged grandparents were trying to find space to rent in the village; room rates were rising rapidly, creating a landlord-renter divide. "Thanks madam, but nobody will care and nobody will help," Sujata's nephew Vishal told me on the phone from Chitapur. He was proven wrong and then right when a politician (who had lost the recent MLA race from Gulbarga) told me the next day I could send the villagers to him for assistance. A group of them made their way to the city by bus, leaving their families in the shade of trees and temples.

When they reached, the politician told them, "Don't agitate or seek compensation, you will be arrested. There is nothing to be done. Besides, you did not vote for me, so what do you want from me now? Go home." Most of them actually had no home to go home to, but I guess it was just a figure of speech.

I tried ringing Rahul Gandhi, who I thought might be looking to get arrested again. "Actually, we feel his action [the last time round in Uttar Pradesh] was not received well by the press," a top aide confided (I protested that a lot of us thought it was great). He heard me out, then put me on to a senior Congress politician in Bangalore who was gracious and gave me more phone numbers. One told me about a scheme by which those who lost their homes could get a Rs 10,000 grant and Rs 10,000 loan, perhaps a small plot of land as well. But, despite my persistence, he has not got back to me with guidance on how to go about availing of the scheme.

"I do not know about encroachment," said one man from Chitapur. "I was born in the house and so were my kids. My father obviously paid someone, or else no one would have let us live here, [that too] with gas and electricity. We have nowhere to go and my wife is pregnant, due to give birth during the rains."

The only surprise anyone expressed about this state of affairs—a government by the people, of the people, for the people treating its citizens as enemies—was over my being so surprised.

"Come on," chuckled M, a journalist with a major Indian daily, "You can't tell me you really think that the plight of the poor in India is news! Listen," he added, "You are going to give up in the end without accomplishing anything, so save your breath and your good standing and let it go. These people will manage, they always do."

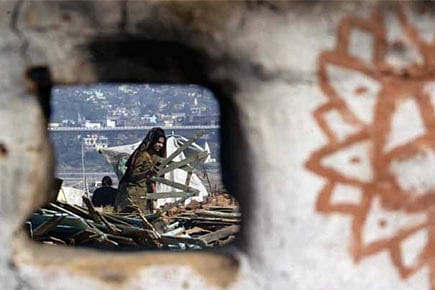

I was reminded of another conversation with a topnotch journalist, D, at a Barista outlet in South Delhi, about a year ago. He had just been to Israel, and had hated it. Curiously, he didn't even know what language was spoken there (Hebrew). "I couldn't stop thinking about the way you guys treat Palestinians," he said, "The way Israelis just sit in their chic' cafés and sip their Mocha Latte while their government demolishes thousands of homes on bogus charges of 'terrorism', taking their land to build roads. It makes me sick."

It used to make me sick as well, with grief and with rage. So, after I burnt myself out as a radical activist, I left, finding my way to India where I could be as spiritual as I wanted and not care too much about social injustice. I've left D the journalist a few messages requesting help in this Chitapur situation, but he hasn't got back to me.