The Ishrat File

Unravelling the political plot

PR Ramesh and Ullekh NP

PR Ramesh and Ullekh NP

PR Ramesh and Ullekh NP

|

18 Feb, 2016

PR Ramesh and Ullekh NP

|

18 Feb, 2016

/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/20862.ishratfile1a_0.jpg)

David Coleman Headley’s sensational disclosure via a video link from the US that Ishrat Jehan, the young woman who was killed in Gujarat along with three others in a 2004 police encounter, was an operative of Pakistan-based terror outfit Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), has evoked much shock, relief as well as denial. The political opposition, various human rights groups and NGOs have cried foul, arguing that Headley, a former Chicago drug dealer who later became an LeT accomplice—he of heterochromatic eyes, with a brownish left one and a bluish-green right eye, and who had conducted a reconnaissance exercise on prospective targets, including the iconic Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, for the brazen 26/11 attack in 2008 that killed 166 people—had named Jehan as part of a quid pro quo deal to help the BJP, which has been under a shadow of allegations that its leaders had approved of staging the encounter. The BJP, for its part, has demanded an apology from the Congress for targeting its top leadership, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi and BJP President Amit Shah, for more than a decade over Jehan’s death. Caught in a bad spot, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, who according to some reports once referred to Jehan as a ‘daughter of Bihar’, has denied ever saying so and has threatened legal action against various media houses for “putting words into his mouth”.

The focus is still on Jehan and Headley, the Pakistani-American LeT hand who had sneaked into India several times, acted as a conduit between several terror groups, plotted against the country, and avoided easy detection thanks to his skin colour and multiple passports. The name that neither Headley, aka Daood Sayed Gilani, nor investigative agencies have bothered to raise is that of a suspected Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh-born LeT associate of Javed Sheikh (formerly Pranesh Pillai), Jehan’s friend who had allegedly inveigled her into the LeT fold.

Based in the United Arab Emirates, Mohammed Mehraj Noorulla, now 41, was only 29 when Sheikh and Jehan were gunned down on the outskirts of Ahmedabad. An investigation by Open reveals that he was reporting directly to a tall, bearded Pakistan-based LeT leader, Muzzammil Bhat, and was in Lucknow when Jehan, Sheikh and others were killed by the Gujarat Police in what the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) had claimed was a fake encounter. Mehraj, as he is popularly known, had flown into India from Saudi Arabia’s capital Riyadh on 26 January 2004, but as soon as he got wind of the deaths of Jehan and Sheikh on 15 June 2004, he returned to Riyadh from Delhi, which he reached via road from Lucknow.

Mehraj, born on 25 May 1975 in the Ibrahimpur locality of Faizabad, carries an Indian passport issued in Lucknow (G2208137; the number of his old passport issued in Mumbai on 13 November 1997 was A4351291), and according to various sources, still travels to India. He had falsely given his father’s name as Noorulla Mohammed Zakir Shaikh, who in fact is his uncle, to obtain a passport from the Lucknow passport office.

It was Mehraj who facilitated Sheikh’s March 2004 trip to Oman at the behest of Muzzammil, from where he had returned in April that year with a satellite phone made by Dubai-headquartered Thuraya Telecommunications Co, and Rs 2.5 lakh in cash, which he used to buy a blue Tata Indica. Originally from Alappuzha in Kerala, Pillai had fallen in love with a Muslim girl before converting to Islam and adopting Javed Sheikh as his name. He had also managed to get a new birth certificate from Grant Road Upper Primary School in Mumbai through a bribe (with his date of birth as 11 March 1972). Sheikh had been in constant touch with Mehraj, but became a crucial link for LeT after acquiring the satellite phone for which air-time charges were paid by a Dubai contact. In fact, in a deposition before investigating agencies, Wasim Raju, an Ibrahimpur-based cousin of Mehraj’s, had admitted that the LeT operative often travels to his home town and stays away from the police radar. Shockingly, CBI had not probed the role played by him despite Gujarat Police recovering call data and other details from the Thuraya satellite phone that Sheikh had used and sharing the information with federal agencies. According to an officer close to the matter, Mehraj was able to beat the rap thanks to “interference” from “politicians at the helm”, especially a Congress leader from Gujarat who didn’t wish to see Mehraj’s name come under the scanner for some strange reason.

“Yes. Mehraj was closely involved in [all] the operations led by LeT men, especially in Gujarat. Ishrat was just part of its operations in the state along with Sheikh,” says Rajendra Kumar, former special director of Intelligence Bureau (IB) against whom the CBI had filed a chargesheet alleging that he had aided the Gujarat Police in staging a fake encounter that resulted in the death of Jehan, Sheikh and two others. Apart from Kumar, three other IB officers had been named in that chargesheet despite the Law Ministry’s denial of sanction to prosecute them. The CBI had said that Kumar had supplied arms and ammunition for the purpose. In fact, the CBI had earlier written to the Centre saying that there was insufficient evidence to suggest that he had supplied arms to state police officers.

Years of torment have taken a toll on Rajendra Kumar’s family. He is cautious and worried about his parents. Kumar, who lives in a modest apartment of a lower middle-class Delhi suburb, says that his mother is now a “vegetable” and that his father is constantly under the weather thanks to the pressure he had to face from authorities to play ball while he was posted in Ahmedabad. Kumar, who was posted in Gujarat in 2002, refutes allegations levelled against him, saying the IB never takes part in encounters. “We don’t take part in such actions. We just give the police evidence that is collected through people, technical resources and through other scientific means,” he notes. According to him, he was targeted by the Central Government of the time, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), because he was a thorough professional who refused to help implicate the state’s leaders in the Ishrat Jehan encounter case. The leaders he refers to are then Gujarat Home Minister Amit Shah and Chief Minister Narendra Modi. He says they began hounding him after he refused to fall for allurements to give false evidence.

According to an Open investigation, on the day the nation celebrated Gandhi Jayanti in 2013, two UPA ministers and a powerful loyalist of Sonia Gandhi met at the official residence of one of them: though it was a national holiday, none of them was in a leisurely mood inside the spacious 28 Tughlak Crescent home in Delhi of then Union Minister of State for Personnel V Narayanasamy.

There was an air of urgency about Kapil Sibal, Union minister for Law and Justice and IT. Ahmed Patel, Congress President Sonia Gandhi’s right-hand man, was there too. The fourth person in the room was former CBI special director Saleem Ali. They were all waiting for Ranjit Sinha, then CBI director, known for his scheming ways. Sinha arrived late, knowing well that political winds had already signalled a power shift in Delhi. Ali was ready to play ball with the trio, and one of them suggested that Kumar had to be ‘tackled’ to incriminate Shah in the Ishrat Jehan case. By the time Sinha arrived, he had to confront four equally zealous people plotting a political conspiracy—Kumar was the top target. But their aims were higher, designed to eliminate potential political threats. Sinha, however, refused to yield to a minister’s goading: arrest Kumar and beat him up. The minister was persistent and Sinha equally defiant.

That was a red-letter day for Kumar. He was being made a victim for being professional, he asserts. A few months later, when the electorate’s pro-BJP mood seemed to abate a bit following the Delhi elections in which the Aam Aadmi Party achieved power, Sinha gave in to UPA pressure, but not to extract fake confessions from a senior IB officer like Kumar; instead, he agreed to file a chargesheet against Kumar. For their part, as regards the case, Congress leaders have denied any wrongdoing.

Kumar, now retired, is wont to look down upon politicians. After all, he is a man who knows too much, a man who is taught to keep secrets to himself—which explains why he is as sceptical as he is cynical. He blames police officer Kuldip Sharma, once the blue-eyed boy of Shah and Modi, for raking up an unnecessary controversy over the Ishrat Jehan case. He also blames a top Congress leader— who he won’t name—from Gujarat with close access to Sonia as the mastermind who altered the original affidavit filed by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), which had ruled out a staged encounter in the Jehan case, by roping in some disgruntled police officers like Sharma, Kumar says. Sharma, who has now entered politics, was not available for comment. Interestingly, Modi had recommended Sharma’s name for laurels when he was Chief Minister.

Kumar also swears by the detailed affidavit filed by the MHA on 6 August 2014 which showed that the inputs provided by the IB for the case were all correct. “After that some people got disgruntled. They pressured the witnesses and tried to prove that the affidavit was wrong through various manipulations,” he says. It was in a revision of the MHA’s second affidavit, he says, that the conspiracy hatched by the UPA came to the fore. A note sent to the Prime Minister said, ‘With these the last hope to grill the Gujarat CM and HM have diminished in despair since this was the last chance to have a strong [Special Investigation Team] with capable people who could have really embarrassed and put Gujarat Ministry in difficulty. Two of the accused are also in close contact and have shown willingness to reveal everything and to become approvers.’ It goes on, ‘The reason behind filing of the [revised] affidavit by the Central government was to dissuade the court from appointing a strong SIT and give a message that even the Central government had approved the act of fake encounter.’ People close to Kumar maintain that former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh as well as then Home Minister P Chidambaram were averse to the idea of targeting him as a means to gain political mileage.

The Headley revelation has come as a relief to Kumar, as he admits. Meanwhile, a section of analysts and pro-freedom groups have questioned Headley’s confessions, saying there are several inconsistencies in his various versions. Headley had allegedly said the following in his interrogation to the NIA in 2010:

“On being asked about Ishrat Jehan, I (Headley) state that in late 2005 Zaki ur Rehman Lakhvi introduced Muzzammil to me. Having introduced Muzzammil, Zaki talked about the accomplishments of Muzzammil as a Lashkar commander. Zaki also sarcastically mentioned that Muzzammil was a top commander whose every big ‘project’ had ended in a failure. Zaki added that Ishrat Jehan module was also one of the Muzzammil’s botched up operations.”

There are those who argue that this deposition contradicts an early part of the report in which Headley claims that he met Muzzammil in 2002 and multiple times after that in 2004 and more. Whatever be the case, Kumar insists that the original affidavits of the MHA—first filed on 28 January 2005 and the second in 2014—were the truest versions which were corrupted later to suit the political interests of the federal masters of the time. He had to pay a price for rejecting their overtures and threats, he claims. In 2009, metropolitan magistrate KS Tamang had indicted the Gujarat Police for faking the encounter, but the report was prepared without any investigation, he adds. Not surprisingly, it is considered ‘highly judgemental and frivolous’ by lawyers and CBI officers alike.

The CBI chargesheet against Kumar, however, was destined to keep the issue alive. Before he appeared before the agency, a senior IB officer had told him “to keep shut” in case he wanted to retire with all the perks typically enjoyed by retired IB officers. Kumar doesn’t elaborate on this, but only suggests that the senior officer may have meant that he shouldn’t talk about other murky deals he was aware of.

For an officer who has been recommended for various medals and rated as an excellent professional by former Home Minister and Congress leader P Chidambaram himself, Kumar was shocked by such treatment.

The senior IB officer mentioned above later approached Kumar suggesting that he become an intervenor in the case in the Supreme Court. Intervenors typically offer a contrarian perspective to an ongoing case. Kumar was initially thrilled by the idea, but it soon dawned on him that if the Supreme Court dismissed his plea, he would be hounded by law-enforcing agencies—and then forced to offer a fake admission, something that the UPA had wanted him to do.

“I realised pretty well soon that it was a trap laid for me to force me to yield to pressure to parrot the official version that political leaders would have benefitted from,” he points out, emphasising that the senior IB officer had assured him that all his lawyer’s fees and other expenses for the case would be taken care of. The thought then occurred to Kumar: why would they take care of his expenses unless they had an axe to grind? He decided that he wouldn’t want to fall victim to the games that politicians play. “My family has been suffering in an inexplicable way for more than eight years,” the IB officer says. He is upset that nobody in the CBI bothered to closely review the mass of evidence that suggests that the UPA Government wanted to cover up the true story of Ishrat Jehan. Perhaps the CBI’s lack of evidence to sustain its arguments against officers charged with abetting the fake encounter serves to give Kumar’s assertion credibility.

Now, following the Headley disclosure, the storm over the Ishrat Jehan case is still raging with activists and opposition parties insisting that what needs to be probed is not whether she was an LeT operative or not, but how she died—whether she was killed in cold blood. It is not easy to disagree with such calls for transparency. It is an altogether different matter that very few people are talking about how to combat terror, what with top-ranking officers vying with one another to land a plum retirement job. In the process, Indian intelligence agencies pursuing inconvenient truths are often forced to bury them. Again, it comes as no surprise that former IB chief Syed Asif Ibrahim is now Narendra Modi’s special envoy on ‘Countering Terrorism and Extremism’ whose job requires him to liaise with countries in the Middle East, apart from Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Blame it on our wheedling politicians. Blame it on the avarice of senior officers looking for a cushy life after service, or on agencies trapped in inertia. The real tragedy is that the truth about Ishrat Jehan remains elusive. Perhaps it is too awkward.

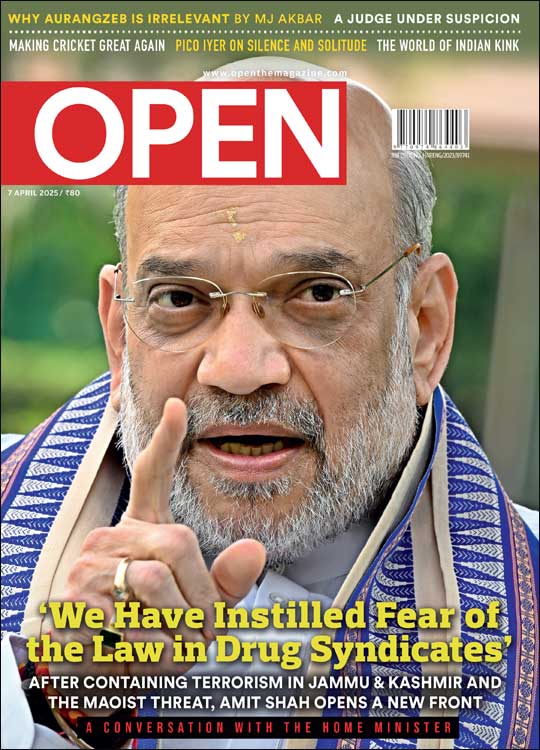

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Calling Japan Kaveree Bamzai

Knives Out in the White House Kaveree Bamzai

Sex, Lies and Espionage Kaveree Bamzai