UP Assembly Elections 2017: Fight to the Finish

Are we heading for another psephological surprise?

Praveen Rai

Praveen Rai

Praveen Rai

|

02 Mar, 2017

Praveen Rai

|

02 Mar, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/UPpolls1.jpg)

THE RUN-UP TO the Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh was marked by a dramatic family feud in the state’s ruling Samajwadi Party (SP), which provided one of the best spectacles on Indian television in recent times. The soap opera within the Yadav clan for claiming the party could’ve given Shakespeare’s play The Comedy of Errors a run for its money. Observers have been watching keenly. The electoral exercise in the state is a political extravaganza due its vast proportions in terms of geographical space, the electorate and representation in Indian Parliament.

The state mandate has a direct bearing on the national politics of India. This was evident in the General Election of 2014, as it voted heavily for the BJP and catapulted the saffron party back to power in Delhi after ten years of political eclipse. The electorate in UP is not only politically well informed and decisive, but also prone to changing its electoral preferences over successive elections and thus keeping competitive politics in the state on tenterhooks. The polls held in the last four years in the state reveal how voter choices keep changing at frequent intervals. In the 2012 Assembly elections, voters ousted the incumbent BSP government and brought back the SP with a clear majority. In 2014, it handed over more than 80 per cent of its Lok Sabha seats to the BJP, and decimated the SP, BSP and Congress. And in the 2016 by-elections held for 11 Assembly seats vacated by BJP MLAs, it gave a mandate to the SP in eight constituencies and to the saffron outfit in only three. The oscillation of voter preferences in UP has not only kept political parties in the state looking for ways to retain their core support base but also pollsters searching for statistical models that can forecast the results correctly.

Opinion polls conducted by media houses just before the elections in UP predict varied outcomes, with one poll giving a clear majority to the BJP while three others point to a hung Assembly in Lucknow. Of the three surveys that suggest no single party will get a majority, two project the BJP as the single largest party in the House, while the other forecasts that the SP will win the highest number of Assembly seats. The pre-polls differ in pointing to the winner and runner- up, but they are unanimous in placing the BSP in third position. The record of poll predictions in UP has been patchy, as they have failed to foresee the magnitude of mandates several times in the past decade. The high number of ‘psephological surprises’ in UP is mainly due to the multi-polarity of party competition, in which a small swing of votes could result in high rates of seat shifts, and the heterogeneity of its electorate. Thus it is crucial to decode the interplay of caste and community factors in the state, assess the dimensions of the issues framed by prominent parties in the fray, and determine their efficacy in shaping voting decisions while discussing the likely outcome of the polls.

First, the demographic composition of the electorate in UP. The state has 41 per cent OBC, 21 per cent Dalit, 19 per cent Muslim and 19 per cent upper-caste voters. Its electoral politics, until the emergence of regional parties like the BSP and SP, was dominated by the Congress whose main support base was a combination of upper-castes, Dalits and Muslims. The rise of the BSP and SP witnessed a major realignment of the electoral calculus and marked the beginning of caste-based identity politics in the state. The majority of Dalit votes shifted from the Congress and moved towards the BSP, while the bulk of Muslim votes gravitated towards the SP, which, combined with Yadav support (9 per cent of the state population) made it a force majeure in UP politics. The core caste base of the BSP and SP was not enough for them, and they had to stitch together a social coalition with other caste communities and religious groups to achieve the critical mass required for winning elections.

Consider the role of Muslim voters. Their voting patterns were similar to those of other caste groups during the period of Congress dominance, but the 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid in the state by religious fundamentalists resulted in a polarisation that saw their votes go in favour of non-BJP parties. Muslim votes play a key role in 73 Assembly constituencies, and the disaggregation of data reveals that in the 2002 Assembly elections, 54 per cent voted for the SP, 9 per cent for the BSP, around 11 per cent for the Congress and 5 per cent for the BJP. The SP, which won the polls that year, was able to win 37 per cent of the seats. In the 2007 elections, the BSP forged an alliance with Brahmins, whose votes combined with those of Dalits and Muslims propelled Mayawati to power in the state. She was able to double her vote share among the religious group from 9 to 18 per cent and win 45 per cent of the seats. In the 2012 elections, the majority-winning SP was able to win 48 per cent of the seats dominated by Muslim voters, with a 39 per cent share of their votes. Muslim votes have been crucial in determining the outcome of the last two state elections, and are expected to play a significant role in the ongoing polls. The SP-Congress alliance will split their votes two ways and will not only have an impact in the 73 constituencies dominated by them, but also those where they number more than 10 per cent of the electorate.

To clinch victory, BSP is counting mainly on the fissures in SP and resultant fragmentation of Yadav votes, a consolidation of Dalit Muslim votes in its favour, and her stand against demonetisation for its negative impact on the poor

The near clean sweep by the BJP in the 2014 General Election, with support cutting across caste and community, has been hailed by analysts as a tectonic shift of politics in UP from a paradigm of identity to development. But this seems to be an aberration, as all the major political parties in the state have been working round the clock to forge social coalitions of caste and sub-caste groups, signalling a return to the usual dynamics. The nature of the electoral contest and the issues offered by various parties in all their dimensions will determine how the caste-community matrix plays out this year to throw up a winner.

AN IMPORTANT ASPECT that shapes electoral outcomes in a multi-corner contest is the set of issues that are presented by parties and those that figure in the minds of voters, which could either be the same or be diametrically opposite each other. It is important to analyse how these resonate with voters.

The BJP is contesting these polls on the twin issues of India’s ‘surgical strike’ against terrorist camps in Pakistan and the demonetisation decision to end black money and corruption in the country. These issues are not only the main plank of the party in UP, but were also in Uttarakhand, Punjab and Goa. The saffron party’s effort to rake up Pakistan for bashing is an attempt to polarise and consolidate Hindu votes in its favour and neutralise the Muslim votes expected to go to its rival parties. It is using the currency exchange issue primarily to project itself as a pro-poor and anti-corruption crusader, and also to target the BSP and Congress, which opposed the move. The party has tried to raise the Ayodhya temple issue as well, by announcing a Ramayana museum there even as it drew attention to the issue of Triple Talaq in the Muslim community. The recent Supreme Court judgment banning the use of religion and caste for garnering votes may have made it a non-issue officially, but it is being used in a veiled manner to mobilise Hindu support. But more than that, the issue of the economy’s re-monetisation is likely to turn the polls into a referendum on the party, a kind of mid-term appraisal of the work done by its government at the Centre.

The track record of UP’s ruling SP government on matters of governance has been far from satisfactory, and the pitched battle between the police and a religious sect in Mathura which left many dead speaks volumes of the breakdown of law-and- order in the state. Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav’s usurpation of full control of the SP from his father Mulayam Singh Yadav in a political coup just before the elections seems to be a clever ploy by the party to redeem its falling popularity and stay afloat in the competition. In a self report card that the party issued listing the ‘good and bad’ points of its rule in UP, it gave full marks to Akhilesh Yadav for all the good work done in the state and projected him as a young leader with a clean image who is committed to the development and progress of UP. The red marks in the report card were ascribed to the party’s old guard, politicians who were opposed to Akhilesh and were either shown the door or stripped of power in the SP. With the popularity ratings of the Chief Minister showing signs of improvement, the state’s ruling party has been using his political recovery and a poll tie-up with the Congress to make it a force to be reckoned with at the hustings. Whether this results in an outright SP-Congress victory will depend on unity within the party, the transfer of votes from one alliance partner to the other, and, importantly, on how much ice the ‘good and bad’ dichotomy cuts with voters in the state.

The Mayawati-led BSP, which is going through a lean electoral patch, began by playing the ‘victim card’, an issue arising from an Income Tax notice issued to her brother which she portrayed as a witch hunt against her. To clinch victory, she is now counting mainly on fissures within the SP and resultant fragmentation of Yadav votes, a consolidation of Muslim-Dalit votes in its favour, and her stand against demonetisation for its negative impact on the poor. Apart from the support of Muslims worried by wrangling within the SP, a backlash against the BJP for the cash crunch caused by demonetisation could have given Mayawati a chance to come back to power in the state. However, giving BSP tickets to members of a dreaded gangster family could nullify her image as a custodian of law-and-order in the state. The BSP appears to be in third position in the electoral race, but the party still has the potential to surprise everyone with its performance.

The Congress, after testing UP’s political waters, gave up the idea of going solo and is content to piggy-ride the SP to retain the number of seats it won in the last Assembly elections and stay politically significant in the state. While the ‘electoral choice’ of voters in UP could depend on the issues laid down by political parties, there is always a possibility of a mismatch between the issues projected by them as important and those that the electorate considers critical.

With eight out of ten voters now having exercised their franchise in the state, the battle of ballots is entering its conclusionary stage, which can still alter the mandate locked up in EVMs. However, the eerie silence of the UP electorate is not only intriguing but also baffling poll watchers. A round-up of the first five phases of elections appears to indicate a subtle groundswell of support for the SP-Congress combine, which has not only overcome the loss of votes due to a change-of-guard in the SP, but also got the alliance arithmetic correct on the electoral turf. The BJP seems to have lost its momentum after takeoff due to its failure in projecting a credible chief ministerial face coupled with diminishing returns of the ‘Modi wave’, which makes it susceptible to a repeat of Bihar’s 2015 electoral outcome. The BJP may need a miracle in the last phases or wait for the eventuality of the Congress’ hand knocking off the SP bicycle to finish first on the victory podium. The BSP, written off by pollsters, seems to have regained its once- dissipating support base (as seen in its 2014 setback) and remains a dark horse.

The Election Commission ban on exhibiting opinion poll results during the elections was blatantly violated by a Hindi newspaper in UP. It published a phoney exit poll after the first phase of voting to deliberately create a bandwagon effect among the electorate in the remaining phases. This not only brought the issue of ‘fake news’ to the forefront but also the cronyism of regional media and its loss of credibility in the country.

An electoral season that began with development as its main narrative changed midway, with leaders resorting to no-holds- barred attacks and their rhetoric dipping to new lows, revealing the ugly face of Indian democracy. The history of electoral politics in UP has been so uncertain and subject to vagaries that there could be another ‘psephological surprise’ waiting in the wings.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

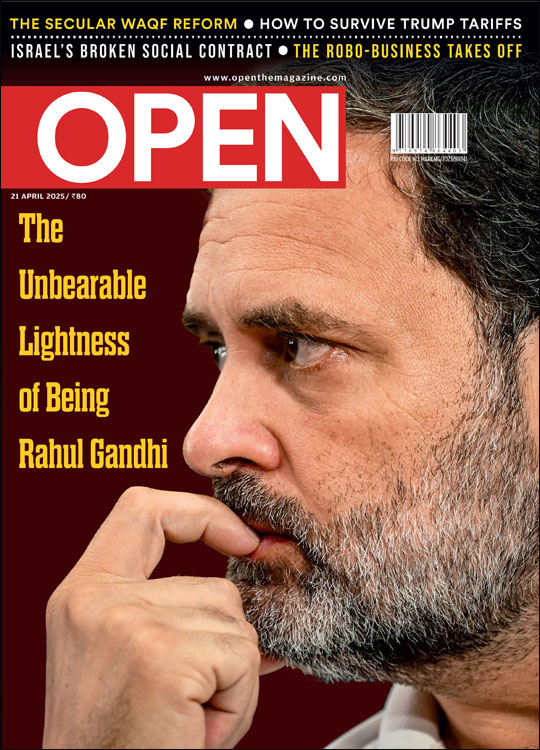

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP

Speculative History Shaan Kashyap