Why Indian Politics Is Anti-Wealth

The pornography of poverty is the aesthetic of the desperate populist. And there is no place more rewarding than India for him.

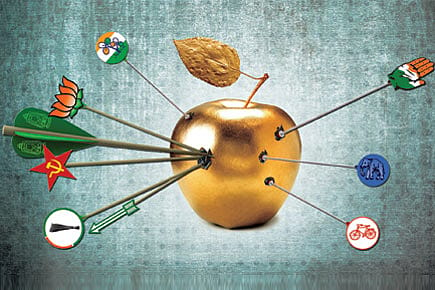

When you are on the side of the people, the nameless and the shirtless, there is no bogeyman more useful than the bloated plutocrat. You don't have to be a demagogue from Caracas or a revolutionary from Havana to demonise the capitalist who thrives on the misery of the masses; you could very well be the average Indian politician from the Left or the Right or the Centre—or from nowhere. Lately, it is Arvind Kejriwal, the only common man among our leaders, or maybe the only leader among common men. This one from one of his most reported stump speeches: "Mukesh Ambani is running this country. Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi are just his two masks. You think that Modi, Rahul or Sonia Gandhi will run the country? Mind it, Ambani will again run this country… In this country, not many can dare to blame Mukesh Ambani." The speaker and his object of derision fit a familiar Indian narrative in which the David armed with nothing but the truth is pitted against the pinstriped Goliath. Here, the lone fighter is always dedicated to the state, and the state is a wretched place where poverty is the slogan that sustains the rage of the fighter, and where the enemy is the Corporate Man, the reaper of the wretchedness, the power behind the puppet king.

This portrait of capitalist as national villain has a hoary history. It goes back to our nation- building days when Third Worldism was in vogue, socialism was the State religion, and ideas such as market liberalism were hallucinations of minds corrupted by Western capitalism. It was a time when the liberated nationalist in a Nehruvian straitjacket internalised socialist virtues of Soviet vintage and placed himself on the left side of history. A time when the wisdom of the State sought to overrule the instincts of the individual. When national happiness was a huge State enterprise, which resulted in the so-called public sector, and when the State's monopolisation of resources was a necessary condition for growth. India was then the model developing country, an inspiration for other newly-decolonised Third Worldists taking their first steps of self-sufficiency. In the beginning, it was said that our Five Year Plan (which continues to be the enduring legacy of the socialist state) was an ideal guide for countries such as South Korea. Maybe in freedom's day after, we needed the intrusive state with a social conscience to set the stage for growth. The trouble began when the State refused to withdraw and became the maker and controller of growth.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

The socialist state was a closed state, and a darker place. It institutionalised the resistance against the evil of lucre. The man who made money was not a success story worth emulating in a country fed on the legends of mendicants and austerity. By the time Indira Gandhi came to power, there was hardly any difference between nationalism and socialism. As Mother India sought direct access to the mass mind, a certain amount of nationalist hysteria was inevitable; and she was exceptionally successful in marketing populism as pulp patriotism. The enemy was a prerequisite for the survival of the compassionate nationalist, and she found an effective one in the businessman, the private entrepreneur. Even as the nationalisation project went on, there was a parallel political enterprise of poverty. 'Garibi Hatao' was a powerful slogan then, and it is so even now. No one realised the uses of poverty as much as the Third World socialist did, and India, where Third Worldism became the mindset of the left-of-centre ruling establishment, was poverty's most photogenic address in the East. Our politicians made best use of it; they are at it still. The pornography of poverty is the aesthetic of the desperate populist. And there is no place more rewarding than India for him. Pornography sells, and when poverty is marketed as wretchedness over which we have no control, it sells more. Prototypes of Kejriwal are easily identifiable in the back pages of socialist rhetoric.

So the average Indian politician in power worked hard to keep poverty at a visible level of utility—and the capitalist at bay. The labyrinthine Licence Raj was the socialist's protective mechanism against the capitalist who dared. In Independent India, the market still remained fettered because the State abhorred the spirit of the individual. The Licence Raj not only perpetuated economic unfreedom, it made India more unequal by banishing fair play. The industrialist still failed to win the trust of the State. It took the sagacity of two men, Prime Minister Narasimha Rao and his finance minister Dr Manmohan Singh, to unshackle the Indian market. It was not full-fledged freedom in the marketplace, but for a country steeped in socialist shibboleths, it was partial redemption nevertheless. At long last, Asia's most evolved civil society got a market to match. Still, somewhere deep within our national psyche, the venal capitalist lurked.

Today, the pioneer of liberalisation is in power, counting the last days of his infamy. Dr Singh had a chance to be the moderniser of India. He had the mind, and the perceived disadvantage of the accidental politician could have been his biggest qualification to lead India—a country let down by the worst habits of politics. He may have succeeded in calling the Marxists' bluff when he refused to make the apparatchiks of AKG Bhavan in New Delhi the unofficial commissars of the UPA regime. But Singh, the much feted architect of market freedom, as Prime Minister was pretty Marxist in his economics; when the fear of the foreign pervaded the political establishment in the wake of FDI-in-retail, he was not there to speak for 21st century India, for its aspirations and possibilities. The erstwhile reformer became the patron saint of restrictions and regulations. It was still not glorious to be rich in India.

That said, nobody from the Right was rereading Adam Smith. Unlike Western Conservatives, the Indian Right was busy marketing life-enhancing mythology instead of celebrating wealth creation, thereby retreating from the economic argument it was born to win. Today, the BJP's prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi wants to turn his blockbuster stump speeches into a conversation with the future of India. It would have been easier for him to slip into the Great Yesterday, which is still the natural habitat for quite a few of his colleagues. Still, Modi's bestselling self portrait as moderniser is incompatible with the party, which at times behaves as if its economic vision is written by a shopkeeper, its argument against FDI being the best example. There is political consensus on the immorality of being rich.

You may argue that it is not entirely Indian. The historian Niall Ferguson writes in his book The Ascent of Money: 'Angry that the world is so unfair? Infuriated by fat-cat capitalists and billion-bonus bankers? Baffled by the yawning chasm between the Haves, the Have-nots—and the Have-yachts? You are not alone. Throughout the history of Western civilization, there has been a recurrent hostility to finance and financiers, rooted in the idea that those who make their living from lending money are somehow parasitical on the real economic activities of agriculture and manufacturing.' The Crash of 2008 came as a vindication for those who wanted some kind of Biblical retribution visited upon the few who controlled wealth. When the Masters of the Universe fell, moralists with a socialist streak rejoiced because the fallen were solely responsible for the unequal world. When capitalism collapsed, the moralists argued, it was the socialist state that came to the rescue. They even cited Barack Obama's stimulus package as a perfect case study of socialism in the time of capitalist crisis.

India too got its moment to play out its socialist script when crony capitalists thrived in the sheltering shadow of this government and gave us so many headlines on corruption. The socialist state struck back with market regulations, stifling the good businessman as well as the bad one. This aggravated the mistrust between the State and the wealthy. So a Kejriwal doesn't look out of place when he demonises an Ambani who runs the new "East India Company". The latest pornographer of poverty is made possible by a political culture that sees wealth as the source of an unequal society. 'The ascent of money has been essential to the ascent of man,' writes Ferguson. In an India that prefers poverty to prosperity, wealth accelerates the descent of man. We are condemned to fall.