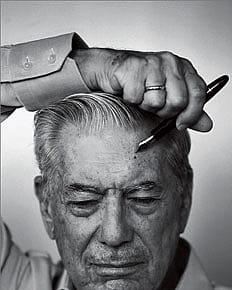

The Discreet Campaign of Mario Vargas Llosa

Mario Vargas Llosa is a believer in Balzac's view that fiction is 'the private history of nations'. In one of his essays, The Truth of Lies, he writes: 'By itself, literature is a terrible indictment against existence under whatever regime or ideology: a blazing testimony of its insufficiencies, its inability to satisfy us. And, for that reason, it is a permanent corroder of all power structures that would like to see men satisfied and contented. The lies of literature, if they germinate in freedom, prove to us that this was never the case. And these lies are also a permanent conspiracy to prevent this happening in the future.' These words could have come from any of the other two members of the trinity that heralded the Latin American Boom—Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes. The so-called el realismo mágico, most extravagantly deployed by the early Márquez, was realism as raw as history, merciless and populated by oversized dictators, bad parodies of Simón Bolívar, and ordinary people defying the wretchedness of their lives with the extraordinariness of their dreams. Together, in varying degrees of magic and ideology, they imagined the lost memories of nations.

We have only Vargas Llosa now, and at 79, his argument with Latin America, particularly his homeland Peru, is as unforgiving as ever. Novels such as The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta and Death in the Andes are his indictment of the revolutionary temptations of Peru's past, but the art of Vargas Llosa, with its invocation of mountain gods and other magical apparitions from the recesses of national mythologies, makes overly political fiction dramatised testaments of dissent. In The War of the End of the World and The Feast of the Goat, where the canvas extends beyond Peru, the dissent—and the drama—becomes truly epic. The Goat, set in the Dominican Republic of the dictator Rafael Trujillo, is a monumental achievement in its depiction of the perversions and pathologies of power, and, along with García Márquez's The Autumn of the Patriarch, the novel brings out Latin America's enduring experiments with tyrannies, bloated fantasies set against unrealised freedom. It is the humanisation of the horror—the autumnal loneliness of dictators—that sets The Goat and The Patriarch apart.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Ideologically, Vargas Llosa would stray away from García Márquez and Fuentes. They all began as romantics from the left side of the argument, and the Colombian and the Mexican would remain there. García Márquez's friendship with Castro was part of Latin American lore, though the novelist was a bit defensive about it toward the end of his life. Fuentes, the brainiest of the three and a diplomat, was a master of abstractions. Vargas Llosa, the hardest realist of the three, would turn right and become an unabashed Thatcherite. He had abandoned Castro chic—the Guerilla Rearmed—long ago. In Peru, he found no romance in the bloodlust of Sendero Luminoso, the Shining Path, for example. 'The achievements of democracy— freedom of the press, elections, representative institutions— are things that cannot be defended with conviction by people who are not in a position to understand them, much less to benefit from them. Democracy will not be strong in our country while it remains the privilege of one sector and an incomprehensible attraction for everyone else. The double threat—the Pinochet model or the Fidel Castro model—will continue to haunt democratic regimes for as long as there are people in our countries who kill for the reasons that the peasants of Uchuraccay killed,' he wrote in the aftermath of a group of journalists' massacre in 1983. The depth of his disillusionment with the salvation theologies of the left would take him from the writer's study to the street. In 1990, he contested Peru's presidential election as a market liberal—and lost majestically to Alberto Fujimori, a Japanese-Peruvian. He could have been Latin America's Havel, but this philosopher would lose only to regain the kingdom of literature. His memoir, A Fish in the Water, ends with a poignant leave-taking by the novelist and his wife as they set off for Europe after the election debacle. 'When the plane took off and the infallible clouds of Lima blotted the city from sight and we were surrounded only by blue sky', he realised that this departure marked a reaffirmation: life would be literature; politics would not spill off the pages.

His new novel, The Discreet Hero (Faber & Faber, 400 pages, £20 ), is a political campaign for the lost Peru, and it is not entirely metaphorical. The novel is powered by the lives—tragic, heroic, and comical in turn— of two men. In Piura, the idyllic life of Felícito Yanaqué, the owner of Narihuala Transport Company, is suddenly shattered by a mysterious letter, with the drawing of a spider as signature, asking for a protection fee. He refuses, for his moral universe is still guided by his illiterate father's advice: "Never let anybody walk all over you." The more he sticks to the principle, the more menacing becomes the threat of the secret extortionists. In Lima, the misfortune of Don Ismael Carrera, an ageing insurance tycoon, begins when he decides to marry his young maid. His marriage to Armida is an act of love as well as revenge: he wants to disinherit his twin sons, the 'hyenas'. Their destinies are bound to converge in the closing pages, and a third man, a figure familiar to Llosa fans, makes it easier. Don Rigoberto, last seen in In Praise of the Stepmother (for me this naughty little gem is a master class in erotic fiction) and The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, Ismael's friend and employee, is all set for a retired life. It will not be easy; the lives of others will change his own.

The life and times of Felícito Yanaqué and Ismael Carrera mirror the violent immorality of a place where the price of honour is emotionally unaffordable. Felícito realises that the spidery web of deceit and betrayal is the making of his mistress and illegitimate son. Ismael Carrera, by empowering his maid through matrimony, challenges the brash new world of his own sons. The world where they play out their heroism may be soap operatic, but it draws into its whirl every element of a country without a value system, where, in the end, a comforting equilibrium can be found only in a police sergeant called Lituma (another character from Vargas Llosa's early pages) or a soothsayer called Adelaida.

Set against the lacerated reality of modernity and progress is the double life of Rigoberto, an insurance man by day and an eroticist voyager by night. In a set piece, Rigoberto and his voluptuous second wife Lucrecia reimagine the sex life of Ismael and Armida and turn storytelling into foreplay. In another, in the privacy of his study, he is looking at the paintings of the Polish-Russian artist Tamara de Lempicka, 'an artist whose fingers imparted an exalted and at the same time icy lasciviousness to these supple, slithering, rounded, opulent nudes who paraded before his eyes…' And in yet another, when he listens to his son Fonchito—the toddler sensualist of In Praise of the Stepmother has grown into a teenager here—narrating his encounters with the mysterious Edilberto Torres, who is onlyvisible to him, at the unlikeliest of places. Is Rigoberto's son an angel? Such thoughts, and the erotic excursions of an otherwise troubled mind, are the only alternatives that redeem the banality of violence. It takes the aestheticism of a nocturnal voyeur to bring a happy ending to the discreet heroism of Felicito and the rebellious romance of Ismael. Welcome to 21st century Peru.

In his Nobel speech, Vargas Llosa said, "I carry Peru deep inside me because that's where I was born, grew up, was formed, and lived those experiences of childhood and youth that shaped my personality and forged my calling, and there I loved, hated, enjoyed, suffered and dreamed." The Discreet Hero is his return to that lost enchantment, that overwhelming disillusionment, with the pace of a whodunnit. It is one of those state-of-the-nation novels written by the last surviving member of a literary club that once ruled the art of storytelling. And in its humanism, it is a celebration of all those discreet rebels who change the terms of living in wretched societies.