Romancing the rogue

In the big bad world, it is again the Russian who happens to be the biggest baddie

Suddenly, the world is bad again. The badness is different from the familiar patterns of the past, which were identifiable in the clarity of the Incompatible Two. The Cold Warriors for more than four decades fitted perfectly into the comic strip perfection of Good and Evil; and there were oversized characters of history who could have come straight out of the sketchbooks of Albert Uderzo to make the period a Manichean saga in geopolitics. Post-Berlin Wall, the communist donned the loose overcoat of the nationalist and played out the hate script in the Balkans for ethnic justice with retrospective effect. Later, it was political Islam that the tea-leaf readers of global trends thought would replace communism as the enemy of the free world, though the mullahs who promised a carpet ride to paradise to the suicide bomber and the ghettoised Muslim youth in the Arab world were unlikely successors to the commissars. In spite of 9/11 and Osama's deification as Islam's Che by his anti- American admirers in the Muslim world, an Islamic imperium in the 21st century was unfeasible, and not just because of the absence of a unifying authority. The idea itself was too pre-modern to be an alternative to democracy. The battles were global, and between two conflicting ideas of freedom.

The Big Bad World 2014 does not have the grandeur of the earlier editions; it's an anthology of antagonisms spread across the world. The theme is still freedom. In Iraq, the jihadi- in-chief of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) fantasises about a global Caliphate. What is alarming is not the fantasy, but the withdrawal of the so-called free world from the Mesopotamian mess where the bloodlust of the tribes is only matched by the divisive power of the official regime. The liberation of Iraq from the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein did not, in retrospect, result in the freedom of Iraqis. Barack Obama's America has no plans to pay the wages of an unfinished war. So in place of Saddamism, we have conflicting versions of Islamism, and no less lethal.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

And elsewhere in the Middle East, the banality of the Israel- Palestine hate fest has acquired a new intensity, and the easiest explanation we hear is coloured by shades of anti-Semitism. Palestinian victimhood is a much shared item in Third World capitals and other places of Left-liberal sentiment. There was a time when Yasser Arafat, the statesman without a state in his trademark keffiyeh and gunless holster, was the bestselling symbol of homelessness in places like New Delhi. Israel was the convenient villain, the artificial state. The falsity of that argument concealed the Palestinian origin of modern Islamist terror and the historical tragedy of a people abandoned and exterminated. The state of Israel is all about being alive—at any cost—amidst countries that deny them even the right to exist. Today, the Palestinian cause is represented not by the soft radicalism of an Arafat, but by the raw fanaticism of the faceless Hamas terrorist. At long last, India is refusing to oblige the Palestinian cause junkies—or to caricature the Jewish struggle for existence as the militarism of the usurper. In what Amos Oz calls one of history's enduring real estate disputes, it is the much romanticised victim—immortalised by the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish and the polemics of Edward Said—who finds no difference between dying and killing. In the absence of a more nuanced expression, we call it terrorism.

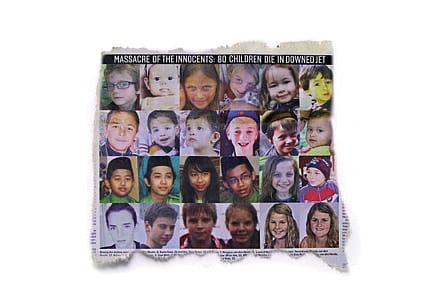

But there is a terrorist in power who is not yet being called one. The faces of 24 of the 80 children killed in the downing of Malaysia Airlines' MH17, published on the front page of London's Sunday Times (see picture), alone will suffice to remind us of the horror this man, mythicised by the aficionados of 'strong leadership' in Delhi and elsewhere, is capable of. His annexation of Crimea went unchallenged, as if it was just another local border crossing; it was actually the first of its kind after World War II. His extra- territorial terror or autocracy at home has not stopped the big powers of Europe and Asia (no need to include Obama's Washington here) from indulging the tallest rogue leader of our times. Vladimir Putin, the post-Soviet strongman, has borrowed the worst from his former employer (KGB) and mixed it with uber nationalism, which has greatly contributed to his soaring popularity. The plane was shot down by a missile fired from a Russian launcher in eastern Ukraine, where Putin's warriors are at work. Ukraine has become the unlamented war of this century; and the terror of Putin, the nationalist with a Stalinist mindset, has not made him a Russian Saddam in the eyes of those countries that swear by freedom. His idea of a Greater Russia is sustained by the enemy's blood—and it is an idea appreciated even by Delhi, which has not said anything about Flight MH17.

In the Big Bad World, it is again the Russian who happens to be the biggest baddie.