Another Foolish Ban

When the Congress and Narendra Modi agree, it can only mean bad news

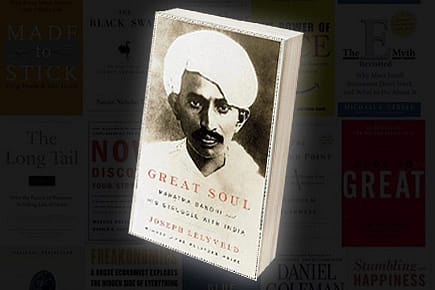

"The government has taken a serious note of the book that has made disgraceful statement (sic) on the national leader. It is demeaning for the nation," Union Law Minister Veerappa Moily said when asked for a reaction to Joseph Lelyveld's Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His struggle with India. Maharashtra minister Narayan Rane echoed his sentiments, and went on to say his government would "initiate steps to ensure that the book does not get published in Maharashtra". It would be tempting to attribute Rane's belligerence to his long stint with the Shiv Sena, but the truth is that the Congress has a long history of falling prey to the stupidity of book bans. This stupidity, though, is not its exclusive preserve. The BJP has followed suit, with that undoubted Gandhian Narendra Modi stating, "The writing is perverse in nature. It has hurt the sentiments of those with a capacity for sane and logical thinking."

In 1989, India became the second country in the world, after that beacon of freedom called Singapore, to ban Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses. It was only one in a series of tragic errors by the then PM Rajiv Gandhi who had long junked idealism for ill thought-out populism. The ban may well have contributed to the subsequent furore that led to the Iranian fatwa against Rushdie. Since then, we have seen a de facto ban through sustained legal manoeuvring imposed by the Reliance Group on Dhirubhai Ambani's unauthorised biography, The Polyster Prince. Now we have Mahatma Gandhi being relegated to the same company. The only thing the ban will achieve is publicity for a book that may otherwise not be as widely read. Only recently, Jad Adam's book on Gandhi, Naked Ambition, a poor effort at compiling what was already known about Gandhi's sex life, had attracted much the same kind of attention. Let us not make the same mistake again; let us make up our own minds about Lelyveld's book.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The key issue here seems to be the alleged homoerotic attraction Gandhi may have felt for Hermann Kallenback, his close associate in South Africa. Several historians and biographers have advanced sound reasons for disregarding this claim by Lelyveld, but that is not the same as arguing that such a claim should not be made or aired at all. Gandhi's words and letters are open to interpretation by others, as he himself would have been the first to argue. The need to debate this claim rather than dismissing it is all the more important because in failing to refute it, we will do Gandhi's legacy a disservice.

What separates Gandhi from any other figure of importance in the 20th century is his insistence that the personal could not be separated from the public. A cleansing of his body could not be separated from the cleansing of the public domain. Control over his bodily impulses could not be separated from his control of all that was not good in the public domain. It was this belief that led to his constant battle with his self, of which the battle with his sexuality was only one part. It also explains his autobiographical outpourings where he seeks to come to terms with both the personal and public.

In this constant quest, homoeroticism, if it existed, would have been another battle the Mahatma fought. It is unlikely that he would not have described it in detail. If public censure was what he was afraid of, well almost everything he detailed of his sexuality was equally shocking for the times. But if it were true that Gandhi had indeed been prey to homoerotic impulses and had suppressed a conscious recognition of it, it would make a difference not in terms of his political legacy, but in those very terms that he chose to judge himself. For this reason, it is up to Lelyveld to make his claim in substantive terms, not on the basis of one line in a single letter. He would not be the first Westerner to make a mess of understanding Subcontinental male behaviour, perhaps just another case of an acquired homophobia from the observer's own culture transferred on to what is largely an innocent holding of hands in public spaces.

And for the same reason, we need to be able to read and confront his claim in full. That is only possible if the book is published in India. Rane and Modi are doing what they have always done, given their narrow-minded politics, but at least the law minister should know better. The Supreme Court's overturning of a ban on James Laine's book on Shivaji should have been on his mind, but the Government seems ready to shed its Executive responsibility for populism. In light of a similar abdication by the Executive of its responsibility in corruption cases, we only have our politicians to blame if India eventually becomes a country governed directly by the Supreme Court.