His Honourable Son-in-Law

The uneasy relationship between the proud Feroze Gandhi and the detached Jawaharlal Nehru

Late on the morning of 8 September 1960, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first Prime Minister, heavily lugged himself up the staircase at Teen Murti Bhavan, the Prime Minister's residence in New Delhi, to his bedroom on the first floor. His energy was sapped and his visage, usually radiant and glowing, wore a fallen look. He slumped into a chair and sat speechless for a good while, visibly shaken. Outside, the temperature climbed to 35 degrees Celsius, and as the sun bore down on the gardens of Teen Murti's sprawling estate, its gates and walkways were thronged with thousands of people. Thousands more continued to stream towards the residence along South Avenue and Willingdon Crescent. By the afternoon the rooms and lawns of Teen Murti were packed with people while outside there was little room left on the roads for any vehicular movement. Politicians of every wing, party workers from disparate political groups, friends, critics, journalists, cronies and diplomats; a myriad mass of humanity, mingled uncontrollably sharing the grief and disbelief their Prime Minister and his family were struck with that day.

At 7.45 that morning, Feroze Gandhi, MP, had passed away following a heart attack the previous day. Since 1952, he had represented the constituency of Pratapgarh (West) cum Rae-Bareli (East) in the Lok Sabha. In a relatively short span of eight years, Gandhi had registered a singularly impressive record as a parliamentarian who spoke fearlessly and objectively (usually against his own party, the Indian National Congress) on important national issues. His interventions were legendary, welcomed and heard by all corners of the House. Among the many tributes paid to Feroze Gandhi, one by Ashok Mehta, at the time Chairman of the opposition Praja Socialist Party, represented the sentiment of many MPs. "Death robs Parliament," he observed, "of an outstanding member, and the underprivileged of a tireless champion. His sympathies were as catholic as his interests were wide. Our public life is not rich in dedicated men; that a man of Mr Gandhi's attainments should have been plucked away in the prime of life aggravates our impoverishment."

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The funeral cortege left Teen Murti Bhavan late afternoon and was followed by a two-mile long procession. Panditji exclaimed, to no one in particular, "I did not know Feroze was so popular… I did not know he had done so much good for the people of India." The remark was a telling one and reveals the extent to which the Prime Minister and his late son-in- law Feroze Gandhi had drifted apart; particularly over their politics in the preceding few years. Pandit Nehru and Feroze Gandhi's relationship had come to resemble a tension-filled duel of regular sparring and frequent misunderstanding, punctuated by occasional flashes of temper. Throughout his life, Feroze held a deep admiration for Pandit Nehru. Nonetheless, this devotion was tempered by a strong sense of perspective, at odds with the prevailing culture of hero-worship the Congress party had of its leader and India's Prime Minister.

The creation of a cult around him is something that alarmed Nehru himself, perhaps more than anyone else, but he was helpless in changing it. As the Prime Minister's son-in-law, Feroze Gandhi certainly enjoyed a level of immunity in the Congress 'Establish- ment' and within Parliamentary circles, much more so than other back- benchers. What is striking is Feroze took advantage of this unofficial immunity to challenge sycophancy and the creeping culture of political 'yesmanship' that had begun to take root in his party.

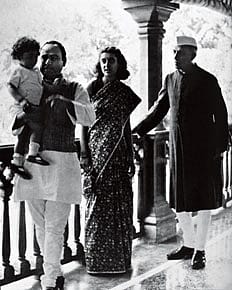

For years, the spirited son-in-law yearned to be taken seriously by his polymath father-in-law. For years the father-in-law, darling of the democratic world and unchallenged leader of his people was not quite sure about the handsome, happy-go-lucky son-in-law who had courted and (against much opposition) married Nehru's daughter Indira. As long ago as 1935, Pandit Nehru had written to his sister Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit about Feroze saying:

'…We have grown fond of the boy because he is a brave lad and has the makings of a man in him. He has our good wishes in every way and we hope that he will train himself and educate himself in accordance with his own wishes and those of his family for any work that he chooses. It is not for us to interfere…'

This passage though fondly articulated, is characteristic of the famous Nehruvian detachment Panditji displayed towards Feroze. Sadly, he only fully realised what a man Feroze had made of himself when he saw the grieving multitudes at his son-in-law's funeral.

Since he was a teenager, Feroze had been actively involved in the Independence struggle, as an organiser, a writer, a 'doer', but he had never really had a job, only a talent for diligent research and a marshalling of facts. Pandit Nehru did much to help Feroze 'start-up' as a family man with professional security when he appointed him Managing Director of The National Herald, Panditji's own newspaper that had begun reprinting in September 1946. A monthly salary of Rs 600 and a lot of hard work saw Feroze and his small family ensconced in Lucknow, finally living the life of a normal, married couple. The campaigns of the Independence movement had robbed them of this normalcy in the past; Panditji's elevation to Prime Ministership ensured the future of their marriage had to endure other strains. The Prime Minister needed an official consort and a host to run Teen Murti, his official residence, and only Mrs Gandhi could do it. "I felt it was my duty to help my father… and there was no one else but me," she had noted. Her position was difficult. Pandit Nehru himself never drew on the Rs 500 allowance for expenses he was entitled to at Teen Murti. Even with Indira Gandhi there as the official hostess and both Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi spending time at the Prime Minister's residence, Pandit Nehru would draw up invoices of their expenses and forward them to Feroze, alongwith the payment. While Indira divided her time between her father, husband and sons (Sanjay Gandhi was born in December 1946), Feroze became resentful of this intrusion in their marriage, and this, perhaps more than anything else, created a wedge between him and his father-in-law.

With his election as MP in 1952, Feroze moved to Delhi at a time when 'he could have risen to the top position in the newspaper world of this country', according to Ramnath Goenka. Nonetheless, it was as a parliamentarian that he became a national figure and though largely forgotten now, his speeches and interventions in the Lok Sabha were based on meticulous detail and wrought serious consequences, usually upon members and sections of his own Congress party. With such few people willing or able to challenge Pandit Nehru, Feroze took it upon himself to correct the course the Congress party sometimes appeared to be taking, prompting some MPs to call him "a misfit in the Congress benches."

Their interactions in Parliament were varied. One particularly memorable exchange between them never fades with repetition. In the fallout of the Dalmia-Jain scandal, unearthed by Feroze, which led to the resignation of the Union Finance Minister at the time, Ramakrishna Dalmia had been arrested. Dalmia's son-in-law SP Jain posted his bail. While the Lok Sabha debated the finer points of the case anxiously, Feroze raised the question, directly to Prime Minister Nehru: "Will the Prime Minister be pleased to state the relationship of the surety to accused?" Panditji replied, "The same as that of the questioner to the answerer" and successfully diffused the tensionof the House.

In a motion discussing the Defence Minister's statement to the Lok Sabha, in April 1960, Feroze Gandhi had taken an aggressive line against his own government, rising on a Point of Order and persistently arguing with the Chair to be allowed to speak: "I raise the point of order because a grave violation of the Constitution has taken place. Where else can I go? You allow every Member there to say what he likes, but when we want to say anything, you say we cannot." The House was in chaos until an exasperated Pandit Nehru himself rose to counsel his son-in-law saying, "…If the Honourable Member feels that an important constitutional issue has been raised, let it be considered. If he wants, let him bring a proper motion to consider it. I do not think it would be proper to consider it in this way." Feroze Gandhi's response to the Prime Minister's intervention was surprisingly deferential: "I am sorry. I would like to express my regrets to you. This is the first time I got a little excited. If I have said anything please forget it." Luckily, this exchange was not expunged from the parliamentary record and gives us a good indication of Feroze's sense of respect for his father-in-law, against the background of his role as an 'unofficial opposition'.

On other occasions, Feroze could be bruising, even in public. At a meeting of the All India Congress Committee, just as Panditji was chiding party members for bringing their spouses to party conventions, Feroze interrupted him, "It wasn't I who brought my wife here…" directing his words towards Indira Gandhi sitting next to Panditji on the platform. Nayantara Sehgal recalls that Feroze, "always welcome at Teen Murti…chose to treat himself as an outsider and behaved with scant courtesy."

Proud of his roots, strong in his convictions and independent in his views, Feroze Gandhi could not bear the oppression of pretence. According to one of his friends, Prema Mandi, "Feroze was egotistical. Any lesser man would have enjoyed the role [of being connected with the Prime Minister] but he had a very deep-seated grouse against himself for being in that situation."

Politically, Feroze Gandhi personified, in full measure, what the Congress party (and Pandit Nehru) originally stood for and what India's Grand Old Party has lost since the breakdown of the 'Nehruvian Consensus'. His was a robust opposition to economic monopoly or crony capitalism, an uncompromising commitment to internal democracy and a strong dislike for the chronic dominance of professional apparatchiks within the party that prevails today. Like his father-in-law, he took the secular foundations and identity of India's culture and politics for granted. Unwittingly, perhaps, he was a more eminent Nehruvian than he cared to admit, or Panditji cared to recognise until it was too late.