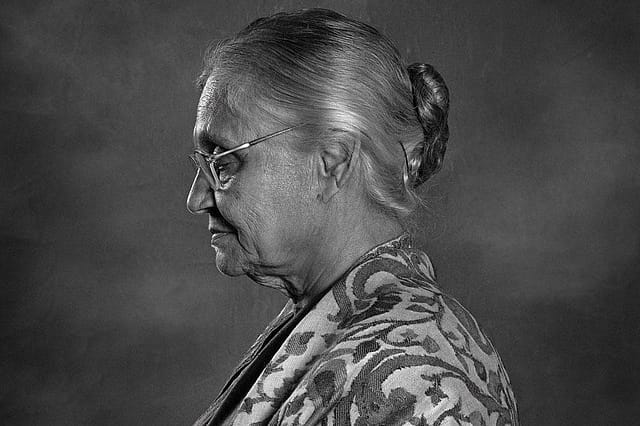

Sheila Dikshit (1938-2019): Leader with a Capital L

HER GLASS-WALLED living room facing the 16th century Humayun's tomb was slowly getting filled with Congress leaders and workers. It was about a week to go for Lok Sabha elections in Delhi this May. In a small room, a few steps down, over breakfast, former Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit exuded confidence that her government's three terms "changing the face of Delhi" would stand her in good stead. It has, forever. But she and her party lost the battle in a Modi wave sweeping across states.S

One wonders if she had sensed that day the writing on the wall for Congress. It neither manifested in her calm demeanour nor her wholehearted campaigning as the 81-year-old leader stepped out into the heat and dust to take on Bhojpuri singer-turned-BJP politician Manoj Tiwari and Aam Aadmi Party's Dilip Pandey in North-East Delhi. For Delhiites who saw the capital change over 15 years of her rule, Dikshit remains the most memorable chief minister. Her appeal went beyond politics in a city where several centuries live simultaneously. When Delhi's longest-serving chief minister and the country's longest-serving woman chief minister passed away last week it was no surprise that opponents, right from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, set aside politics to pay homage to her.

It was at a time that Delhi was facing an onion crisis, with prices of the vegetable rising, that Dikshit defeated the BJP to take over the capital's reins in 1998. Over the next five years, she focused on development, making it her governance mantra and the bedrock of her political journey. From being a city in distress, hankering after an effective public transport system, roads and clean air, Delhi opened up the throttle making way for Metro rail, CNG vehicles and flyovers criss-crossing the city, which is perpetually bursting at its seams.

Metro man E Sreedharan recalls how she left all technical decisions to him and never interfered in the work on the Delhi Metro. "I found her extremely elegant, never played politics and always supportive of the Delhi metro. I consider her an excellent administrator," says Sreedharan, who joined the Delhi Metro in November, 1997, less than a year before Dikshit became chief minister. In his 14-year tenure, she was chief minister for over 13 years.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

When a compartment in the train was reserved for ladies, Dikshit was disappointed and asked why the Metro was not enforcing gender equality. "When I explained the reasons, she accepted the decision gracefully," says Sreedharan. Last month when the AAP government proposed making travel in public transport in Delhi free for women, Dikshit dismissed it as a move which should be seen politically. Sreedharan recalls another instance, soon after she took over as chief minister, when the alignment of line number one from Tees Hazari to Pulbangash was changed by him to reduce the number of structures to be acquired. Those affected were up against the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) and demanded that the original alignment be restored. Dikshit called a meeting in which Sreedharan explained the reasons. After listening to him, she said, "I will not question the technical decision taken by Mr Sreedharan as I feel he is the best person to decide on such matters. So the new alignment will stand. I understand your problems and will take necessary steps to resolve them." The protestors accepted it and dispersed.

"I had access to her any time of the day whenever I had a problem with the state government. She highly appreciated my emphasis on punctuality and cleanliness of trains and stations," says Sreedharan. It was during Vajpayee's regime that Delhi got its Metro. Dikshit made sure political differences did not come in the way of governance, her constant refrain being people choose leaders to deliver on promises.

JUST LIKE SHE left the Metro to Sreedharan, she encouraged arts in the city but left its creative pursuits to the artists. Filmmaker Muzaffar Ali, who directed Umrao Jaan, says it was rare to find a person like her responding to ideas in a huge space like Delhi. When he came to Delhi from Lucknow in 2000, she met him and asked if there was anything she could do. He said Delhi was a city of Sufi saints. Dikshit was supportive of any effort to bring out the essence of Delhi, an amalgam of diverse cultures. That is how Jahan-e-Khusrau, a three-day annual World Sufi Music Festival held at Humayun's tomb, took off. "Even after she was out of power, she came to attend it, as anyone else in the audience. She was always warm and humble with the artists. She saw the artist behind the art. She didn't curate, but she felt the art," he says. Last year, the theme of the festival 'Yamuna—Dariya Prem Ka' revolved around the river that cuts through the capital. Ali says the artist community was always associated with government and in Dikshit's absence, they would feel bereaved. "She knew that if she asked for anything from anyone even in another party, she would not get no for an answer. I wanted to see her in a role beyond politics," says Ali.

Dikshit did pursue writing, bringing out an autobiography Citizen Delhi: My Times, My Life in which reminiscing her campaigning in Uttar Pradesh's Kannauj parliamentary constituency in 1984, she says that on some days 'I certainly felt as if, like Alice in Wonderland, I had fallen down a rabbit hole. Being new to the scene, I found myself being borne away by the insistence of well-wishers around.' Her rivals in UP dubbed Dikshit, an English-speaking political greenhorn, an outsider. She won the election, entering Parliament for the first time, and became a minister in the Rajiv Gandhi Government.

It was in Delhi that she spent most of her life after she left Kapurthala in Punjab where she was born to an army officer. She studied at the Jesus and Mary Convent and Miranda House and married Vinod Dikshit, the son of Union Minister Uma Shankar Dikshit. At the helm in Delhi, she realised that the city had to be administered and responded to with a deep sense of understanding.

"We could honestly tell it to her face that she was wrong. She would hear us, however contrary it would be to her line of thinking. She would generally go ahead and do what she thought was right," recalls Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) director Shakti Sinha, who was principal secretary of finance and power during her tenure. Sinha was earlier private secretary to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and joint secretary in his PMO. Dikshit took that as an added advantage saying she would be able to utilise his experience of working in the PMO.

"Her concern for another human being dominated her politics. No matter what her own stress was, she would ensure a visitor is being properly looked after. Her own troubles would be forgotten if somebody else's problem had to be solved," says Congress leader Pawan Khera, who had joined her in 1998, when she was made president of the Delhi Pradesh Congress Committee.

By the end of her third term, Dikshit started facing allegations of involvement in irregularities in contracts for equipment for street lighting during the 2010 Commonweath Games. The charges were denied by Delhi Chief Secretary PK Tripathi. What saddened Dikshit, according to those who have closely known her, was that the CWG did not get its due credit. Her concern for the environment, in a city where pollution levels have risen menacingly, reflected even in her last wish. She was cremated in a CNG crematorium, introduced in Delhi during her tenure. She wanted a "full stop" to her political career after 15 years in power in Delhi, only to realise "there are full stops in other spheres of life. But there are no full stops in politics."