Padmavati Between Fact and Fiction

THE LATE PROFESSOR KS Lal, a historian admired especially by Hindu rightists and who authored History of the Khaljis, had dismissed any talk of Alauddin Khilji’s ‘carnal desires’ for the 14th century Chittor queen Rani Padmini. He termed it a figment of latter- day imagination. Like many historians, he found no mention of Padmini in any early account of Khilji’s siege of Chittor.

It was 200 years after Khilji’s death, during Sher Shah’s reign, that Sufi Malik Muhammad Jayasi wrote a ballad about an imaginary obsession of Khilji with Padmini. Since the 16th century, oral and written versions of her legend have spawned a genre of sorts, as captured beautifully in the book titled The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen: Heroic Pasts in India, c. 1500-1900 by historian Ramya Sreenivasan. In hindsight, it was Jayasi who set the trend. Notwithstanding all this, serious historians of all persuasions— including Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod, who wrote Annals and Antiquities of Rajputana—have found no proof of Khilji’s efforts to abduct Padmini or that he was besotted with the queen.

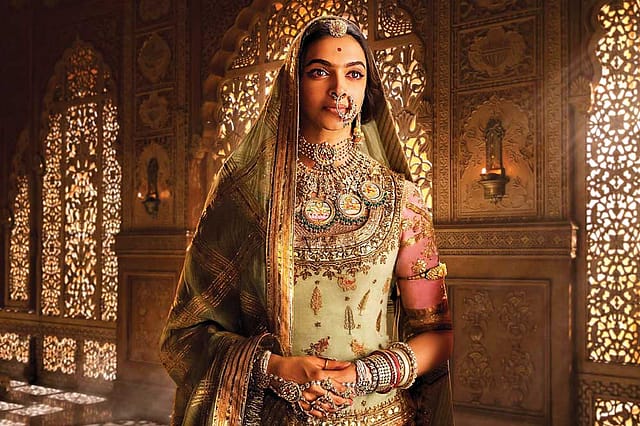

The entrenched current story of Padmini’s life resembles the modern Amar Chitra Katha graphic novel version that portrays Khilji as a reckless womaniser who would do anything to get hold of other men’s wealth and women. And Padmini is a paragon of the so-called Rajput virtue of preferring death to dishonour. She is now more famous as Padmavati, thanks to the Sanjay Leela Bansali film due for release on December 1st, starring Deepika Padukone in the role of the Rajput queen and Ranveer Singh as Khilji. The movie, long before its release, earned the wrath of caste groups and trigger-happy enthusiasts opposing the ‘vulgarisation of history’ of Hindu legends in the name of art. There have been several cases of burning of the movie’s posters and even vandalising of its sets, besides an assault on the director while shooting the film in Rajasthan. Even the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh has warned that its release would hurt Rajput sentiments. Various caste outfits have vowed to resort to violence against its screening, alleging that Khilji and Padmavati are shown as being in love in the movie.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Artists taking liberty with history is nothing new, but lately the clamour about singling out Hindu characters while treading carefully on legends of other religions has gained in momentum. Notably, all that we know of Padmavati so far is also based on fictional interpretations of history, oral and written, centuries after her death. Of those, the narrative that the majority of the current generation of caste supremacists and others are familiar with is not the one based on rigorous historical studies, not even by the likes of Professor Lal.

The Amar Chitra Katha version however takes the cake. The graphic novel starts with an imagined visual of Chittor, claiming it to be the ‘soul of Rajasthan’. The next disclosure is this: ‘Its history is the saga of Rajput valour.’ Padmini’s story starts with her future husband, Ratan Sen, projected as an avid patron of music and the arts with the best collection in the world. The next scene is a visiting bard telling him that his palace has everything of beauty except Padmini. “Nothing equals the beauty of Padmini,” he tells the ruler of Chittor, who immediately sets out in pursuit of the Sinhala princess and marries her.

Khilji enters the picture after being instigated by a Brahmin from Chittor who had just been thrown out of the kingdom for trying to deceive the king. Humiliated and furious, Pandit Raghav Chetan meets Khilji in the woods on his way to Delhi. The Sultan, too, is hunting in the forest and Chetan mesmerises him with his flute. The Brahmin fills his mind with ravishing visions of Padmini who, he tells the sultan, is the most delicate and beautiful woman in the world.

Khilji then departs for Chittor with his forces. Under instructions from Chetan, he announces that Padmini is like his sister and so wants to meet her. He sends a messenger and Ratan Sen agrees. Padmini, however, is willing to show herself only in a mirror so that sultan doesn’t cast his evil eye on her.

Bewitched, Khilji pretends to leave and at the last gate takes Sen prisoner. He will only free him in exchange for Padmini. Somehow, Gora and Badal save Sen from captivity by posing as maids. The angry Khilji pledges to avenge the insult and lays siege to Chittor fort. Food supplies dwindle and the only option left for Padmini and other women is jauhar (self-immolation). At the end, the women in the fort commit suicide to save their honour, and the men, clad in saffron, venture out to fight Khilji and his forces, only to be vanquished. The graphic novel ends with Khilji wondering why the Rajput men fought his soldiers despite their being sure of a defeat and why their women killed themselves. Chetan is shown telling the sultan, “Your majesty, you will never understand.”

Of course, this tale has sprung from the imagination of storytellers, and no historian has vouched for such a version of events. Sentiments often run deep; yet, since discretion is the better part of valour, the zealous use of fiction to protest artistic freedom borders on the comical.