An Island in Time

Two upcoming photo exhibitions capture contrasting moods in Delhi's Shahpur Jat

Concurrent to the forthcoming Delhi Photo Festival will be several satellite shows, included in the festival's programme as 'partner gallery exhibitions'. Among these are two bodies of work shot in and around Shahpur Jat, where Open's office happens to be located. Well, almost. Starkly dissimilar in concept, aesthetic and approach—one rooted, a portrait of a community with a generous sense of place; the other distinctly un-placed, resisting location in pursuit of a mood, a state of being—both works tap into something essential about this dense historic village in its contemporary state. Philippe Calia burrows inward to find fullness, community, an immensely reassuring vitality, while Ishan Tankha wanders outward, toward the periphery, finding pauses in the bustle, a gentle desolation also encountered elsewhere at the other end of the continent.

Philippe Calia's work, A Summer in Shahpur Jat, was commissioned by Kaushik Ramaswamy and Akshay Mahajan of Printer's Devil when they found themselves in possession of a large-format film camera, which they were keen be used to create a body of work based in Shahpur Jat—perhaps along the lines of the series Small Trades by Irving Penn, or August Sander's People of the 20th Century. They identified Calia as someone who'd be able to use the camera, and who might bring a grounded outsider's eye to the place. What began as a portraiture project turned into what Calia calls "a social experiment". By announcing his presence in a flyer, opening himself up to questions and photographs on-demand, Calia made himself a fixture in the village—a familiar face rather than a lingering intruder. The resulting intimacy defines the work, transforming what could have been an ethnographic survey into an extended family album.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

The subjects of these portraits—referred to with affectionate nicknames like 'Mr India' by Calia and Ramaswamy—are not alien or exotic or objects of condescension as subjects of similar studies so often become. Though frontal in their composition, with subjects looking at the camera in carefully constructed frames, the photos are not faked. They are a panorama, not a pageant. The subjects are not being asked to perform anything, nor to surrender themselves and their contexts to some arbitrary visual category dreamt up before the fact. The longer you look, the more effortlessly cheerful they seem, gifting you a sense of upbeatness, perhaps of in-touchness. They evade the voyeurism, the forced pathos, the drive-by alienation that ethnography, documentary and street photography often lapse into. The portraits have a dignity and openness and, despite being very diverse, a sense of being part of a continuum. Impossibly, all these people, pictures in their little niches, seem to make sense as a collective in a way they might not otherwise.

In addition to the portraits, a view of the monument unfolds across a beautiful triptych, an open parenthesis for an ongoing project (1). The portraits are also punctuated by a diptych: the same galli twice, in the daytime and the night, in which Calia has employed a selective focus to terrific effect. In the day shot, the photo converges where the street does, and in the second, breathtakingly, the eye hurtles into a narrow sliver of space between buildings. The work is, unmistakeably, a portrait of a place.

It is clear Calia has spent a summer hanging out, taking the pictures people ask him to take, getting to know them, inhabiting their space, becoming enfolded. The result is ease, visual fluency, unperformative work.

Ishan Tankha's Inbetweeners is in fact two series, connected by a similar sensibility. One was shot in Tokyo in 2006 over the course of a week, the other in Delhi, in Shahpur Jat, over the course of several months. As a visitor in Tokyo, Tankha sought parts of the city that were a little slower than the rest, islands of respite from its general pace. "Everything rushes past you in a new city," he says; he looked for places to linger, inaccessible spaces into which you cannot be invited but must thrust yourself. A day spent in this way with a group of Harajuku girls resulted in several close portraits which, taken together, convey a collective remove, a public inwardness. Other portraits show people daydreaming, idling, waiting. Then there are other photographs that seem to lie between frames: fish waiting on a sidewalk, a reflection, an advertisement, non-events—what Tankha describes as "the opposite of a decisive moment".

Such moments are the subject and pursuit of Inbetweeners—moments between other moments, moments of pause interrupting the bustle of a city, "moments of rupture", but gentle ones.

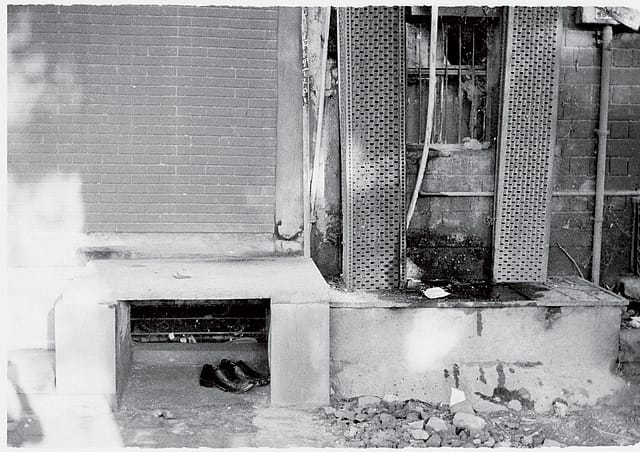

Turning his attention toward the ragged, often sinister periphery of Shahpur Jat where he spent so much time, Tankha "didn't think [I] could find something gentle". But that is precisely what he found. Pools of shadow, corners of neglect, but also calm. People not going anywhere in particular, taking a break or a nap, time spent between tasks. The photos answer in the affirmative Tankha's question, posed in a statement of inquiry: 'Is it possible for photography to disrupt the image of the city's relentless march, to offer a chance to reflect without despair?'

It is, indeed, and Tankha's photographs show these disruptions can have the texture of a puddle on the pavement rather than a fist through a window. Frozen moments only possible in photographs: still, yet breathing, somnolent, simmering. When they go up at the Japan Foundation later this week, the two series will face each other; two cities in a rare, soft mood, reimagined through fragments, taking a moment out of their bustle to breathe.

— Text by Devika Bakshi

Note: A correction was made after this article was published