The Cult of the Lingam

Whoever lives his life without honouring the lingam is truly poor,

sinful and without luck. To honour this giver of joy is worth more than

good works, fasting, pilgrimages, sacrifices and other virtues

—Shiva Purana, Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy

TRACING THE STORY and evolution of the linga and dipping into the re-telling of the many myths and Puranic tales in Hindu tradition, show the linga becoming a potion of magic, fertility, procreation, vitality and inhibited continuous pleasure. The well spring of lust, desire and culmination of love and longing, the penis is both an emblem of power and pleasure. In that sense, the phallus is perceived very differently in Hindu mythology and culture as opposed to the Judeo-Christian religion, where sex and pleasure are antonyms. In ancient Hindu culture, the phallus then becomes the most important tool of carnal pleasure. According to one story, when Kamadeva, the god of love, disturbed Shiva’s meditation trance so he falls in love with Parvati, such was Shiva’s fury that he punished Kamadeva by giving him marks of a vagina on his face! In the same sacred landscape, there is a story which has a detailed description of the sexual act between two male Gods, Shiva and Vishnu, that led to the birth of their son Ayyappa, the celibate god. This can only happen in the religious culture of India where every god has a wife and primordial gods like Shiva and Parvati are known for their passionate lovemaking.

Shiva, the god, symbolised by the linga in India, figures in many stories related to the erotic in texts. In one of the versions, the Kamasutra first came into being as Nandin recited it while he was overhearing the sounds of Shiva and Parvati’s lovemaking. According to the scripture, “While the Great God Shiva was experiencing the pleasures of union with his wife Uma for a thousand years as the gods count them, Nandin went to guard the door of their sleeping chamber and composed the Kamasutra.” In the last chapter of the Kamasutra, aphrodisiacs and techniques are outlined which are believed to strengthen the phallus.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

Shiva, being an ancient, primeval god, is mentioned in the Vedas as Rudra, as Pashupati—the lord of animals—in Indus Valley seals and seen extensively in wayside shrines all over India as votive offerings of snake stones. In the Kamasutra, Shiva is represented as the linga, the marker of male identity. Sir Richard Burton and Foster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, the two translators of the text, did this to bring more acceptability to the text as it was considered erotic by Victorian scholars.

The linga brought in the spiritual into the erotic aspect of the Kamasutra, extending into the mainstream retelling of the text. This meeting of the erotic and the spiritual is widely seen in artistic interpretations and representations on medieval temples found at sites like Khajuraho, Konarak and Modhera, to name a few. These temples and structures are full of amorous couples in ‘mithuna’ or having coital sex , where the male erect penis is not an uncommon sight. The famous Khajuraho temples, built between 950 and 1050 CE, carry carvings that highlight the sexual union between the different Indian gods and goddesses. These carvings suggest that the temples were not only for performance of prayers but also a place where the four purushartha or the four aims of human life according to Hindu philosophy: dharma (righteousness), artha (monetary value), kama (desire) and moksha (salvation) were taught. Be it literature, poetry, popular culture, or simple way side shrines, the phallus is vital is every aspect of life in India.

Due to being such an important part of everyday life, the phallus has led to the erection of many stories, myths, legends and devotion around it. The myths around it are most connected to Shiva—to understand this, it is perhaps important to understand the story that involves the three gods of the Hindu trinity, Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva. According to that Brahma and Vishnu were once quarrelling over who was the supreme god. Brahma claimed he was the Creator and hence supreme, while Vishnu claimed he was superior as he was both the Creator and the Destroyer. Just then, Shiva’s voice sounded from within a pillar ablaze with light, declaring that he was pre-eminent as he was the Creator, the Preserver and the Destroyer. Astonished, Brahma and Vishnu put aside their quarrel and journeyed in opposite directions to ascertain the size of the lingam—the pillar of light. The Linga Purana posits that the lingam is rooted in the formless and the non-manifested. Therefore, Shiva is himself without the lingam. It belongs to Shiva and the one who possesses it is the Supreme Being. In that sense, the phallus is the foundation of the whole world; everything issues from it.

The lingam, known more as a shivalingam, is a specific icon of the Hindus and has its own unique representations. Shaivism—the strand of Hinduism that worships Shiva—is an important sect and the phallic symbol of the lingam is a constant icon which is a permanent feature in Shaivism and its regional representations.

A. Danielou in Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus, translates from the Shiva Purana, “I am not distinct from the phallus. The phallus is identical with me. It draws my faithful to me. Therefore it must be worshipped. My well-beloved! Wherever an upright male organ is to be found, I myself am present even if there is no other representation of me.”

The lingam/penis/phallus/ becomes an important ‘member’ of pleasure, desire and seed-giver. And since it is a symbol of Shiva, it is a stronger part of his identity and an icon of worship, reverence, fertility, vitality and energy.

The phallus plays a dual role as the organ of procreation and the bringer of ‘ananda’ or divine ecstasy, which comes about from the union of the lingam/ phallus and the yoni/vulva. Pleasure and desire are manifested through the phallus. The vulva and the phallus, as well as the bodily fluids, were considered essential in the fertility rites within tantric philosophy. In this philosophy, the ananda ultimately gives way to detachment and enlightenment. In some tantric sects, the shivalingam is depicted as a phallic symbol and the base as a vulva, or yoni. While the lingam represents the ubiquitous or static absolute, the yoni represents the dynamic, creative energy of God, the womb of the universe. This touching of the lingam and yoni has its own unique ramifications. It also throws light on the way the cult of the lingam is understood, expressed, explored, worshipped and used as a metaphor in popular imagination. In Hinduism, the yoni is the emblem of the feminine cosmic creativity (Shakti), the highest symbol of Devi, who is also the consort of Shiva. Symbolising this union, Shaivite temples have a circular yoni pedestal for the lingam. This ancient Hindu interpretation of the linga and yoni is entirely metaphysical and psychological.

Clearly, the lingam—be it in a sculpture or painting—is viewed as a metaphor and motif for the primordial god Shiva in all his forms—as Rudra (Lord of wind), Mahakaal (Lord of all times) Nataraja (King of the art of dancing), Ardhanarishvara (Androgynous form of Shiva and Parvati), Hari Hara (Remover of sins and the Destroyer) and Somesvara (Lord of all).

References to the phallic cult are found across the subcontinent and especially in south India. The first ithyphallic symbol dates back to the Indus Valley civilisation. Danielou speaks of how the “rough and courageous Aryans discovered a marvellous civilization in India—cities of gold and silver with splendid palaces and incalculable riches, offering every pleasure. These cities were inhabited by a dark-skinned people, who worshipped the phallus and the snake and who fought bravely against the invader.” The phallus was not mentioned in Vedic writings and the Aryans seemed unaware of the concept. There is, however, a reference to the Shishnadva, or the phallic god in the Rig Veda. His worship was banned due to the socio-cultural mores that prevailed then, probably because the phallus was associated with pagan cults that incorporated black magic and sorcery in their worship rituals. The revival of Shaivism in the second century BCE redefined these attitudes towards the phallus in Vedic texts.

Emergence of the Lingam

“The linga is an oblong-shaped object worshipped by Hindus around

the world as a symbol of Lord Shiva, the God of Transformation, who

is beyond all forms. The circularity of the linga represents the endless,

all-pervasiveness of Divinity.”

—Mat McDermott

INDIAN CULTURAL TRADITIONS, particularly those related to Hindu gods and goddesses, abound with innumerable stories both in the ‘margi’, or high culture and the ‘lokdharmi’, or popular culture. And Shiva is regarded the first amongst the holy trinity of the primordial gods, his lingam becomes the object of greatest sanctity, even more, sacred than any anthropomorphic in that age, as stated by Stella Kramrisch, a leading art historian and a specialist on India art.

In fact, the shivalingam is the most emphatic icon of Shiva. The beginnings of the shivalingam go back to the Indus Valley civilisation, the first physical representation of the powerful erect penis which is also known as the urdhavalingam—a symbol of active procreation and Shiva’s potent, fiery and fecund semen. However, the very concept of Shiva goes even further back.

From the Puranic period onwards, be it the Shiva Purana or the Shaiva Agama texts, there is a continued reference to the shivalingam. There is plenty of evidence to demonstrate that people from pre-modern India associated the iconic form of the lingam to the male sexual organ. In his poem ‘Garland of Games’, the eleventh-century Kashmiri Sanskrit poet Kshemendra wrote, ‘Having locked up the house on the pretext of venerating the lingam, Randy scratches her itch with a lingam of skin.’ The same parallelism is even seen in the Kamasutra, as the translators write that they “adroitly manage to escape the smell of obscenity,” by using what they presented as “the Hindu terms for the sexual organs, yoni and lingam,” throughout their translation. Even though the use of lingam and yoni by Burton and Arbuthnot is problematic, because the terms do not represent the text, it was a deliberate ploy to avoid any kind of pornographic charges. Both Arbuthnot and Burton were well aware of the religious sanctity of the lingam and the yoni, as they said, “There is in Hindustan an emblem of great sanctity, which is known as the Linga-Yoni.”

In fact, the deliberate use of the word ‘lingam’ in the Kamasutra even by Yashodhara, the thirteenth-century commentator of the text, was probably done to bring in the religious and the spiritual into a secular text. As Wendy Doniger [author and Indologist] writes, “In fact, some Hindu traditions say that Shiva cannot be described or depicted so that an impersonal phallic stone is an appropriate symbol to express his divinity.”

Stella Kramrisch presents a deeply philosophical construct of Shiva in her book, Presence of Shiva. Shiva in his numerous manifestations is seen as a pillar of light, superior to the other two parts of the holy trinity of Brahma, the Creator, and Vishnu, the Preserver. Shiva appears in the form of a pillar of light shaped like a penis, or lingam, through which both Brahma and Vishnu traverse trying to find a beginning and an end. Shiva asserts his supremacy by showing no beginning and no end to both Brahma and Vishnu, as the two are unable to end their journey. Shiva, also through this metaphor, expresses the timelessness of time, ie Mahakaal or the lord of time.

The lingam over the years has become the most forceful representation of Shiva, and every Shiva temple has the presiding deity as a shivalingam. The complete shivalingam is an erect penis, usually a simple, smoothly polished cylindrical or egg-shaped stone resting on a vagina-shaped base known as the gauri-patta or yoni, thus, showing the conjoining of the male and female principle. This is similar to the Greek concept of pleroma. The simple cylindrical shape of the lingam is the font of life and the entry into death. In a temple, the axis of the linga and the central peak of the temple roof are in a direct line—representing the lingam of light. The erect phallus is classified into three parts. The lowermost is square and concealed within the pedestal; it represents Brahma, the creator and the gravitational power and holds and shapes the universe. The second section is the octagonal section in the centre which symbolises Vishnu, the main power which gives birth to matter. Lastly, the uppermost part is cylindrical and an emblem of Shiva, the powerful force of expansion. The base of the structure is none other than the yoni in which all matter realises its individuality.

Most shivalingams in the temples of India, particularly in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and most of northern India, have stone lingas. Stone worship is a universal phenomenon going back to the prehistoric times. Many sanctified stones have been associated with spirits, fertility and as gateways to other worlds—the Ka’aba in Mecca, the Greek Omphalos, the tomb of the sacred python in Delphi, the Rock of Ages, and the Semitic Beth-Els, ie Bethlehem. The shivalinga, too, is an emblem of such archetypical sentiments.

While the lingam or Shiva as a concept or manifestation is not mentioned in the oldest book of knowledge of the Hindus, the Rig Veda clearly mentions Rudra, a manifestation of Shiva, as does the male organ, called ‘kapruth’ which could mean expanding or extending pleasure. According to some scholars, the Vedic god Indra is encouraged to strike down “those whose god is the phallus” or those who take enjoyment in playing with the phallus.

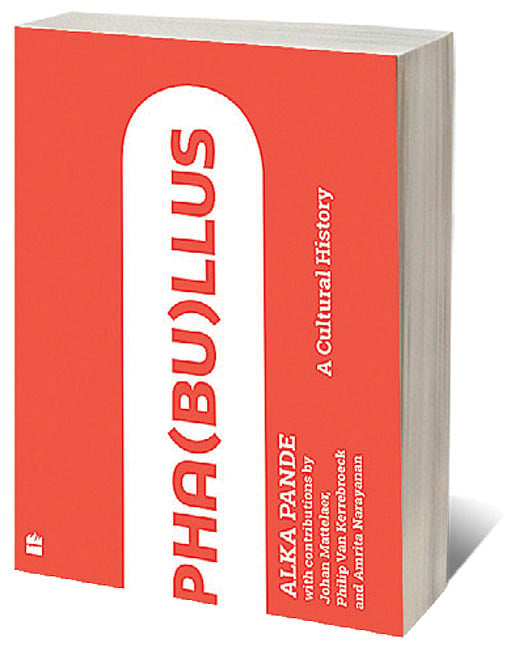

(This is an edited excerpt from Pha(bu)llus: A Cultural History by Alka Pande | HarperCollins | 240 pages | Rs 1,999)