Untameable Divinity

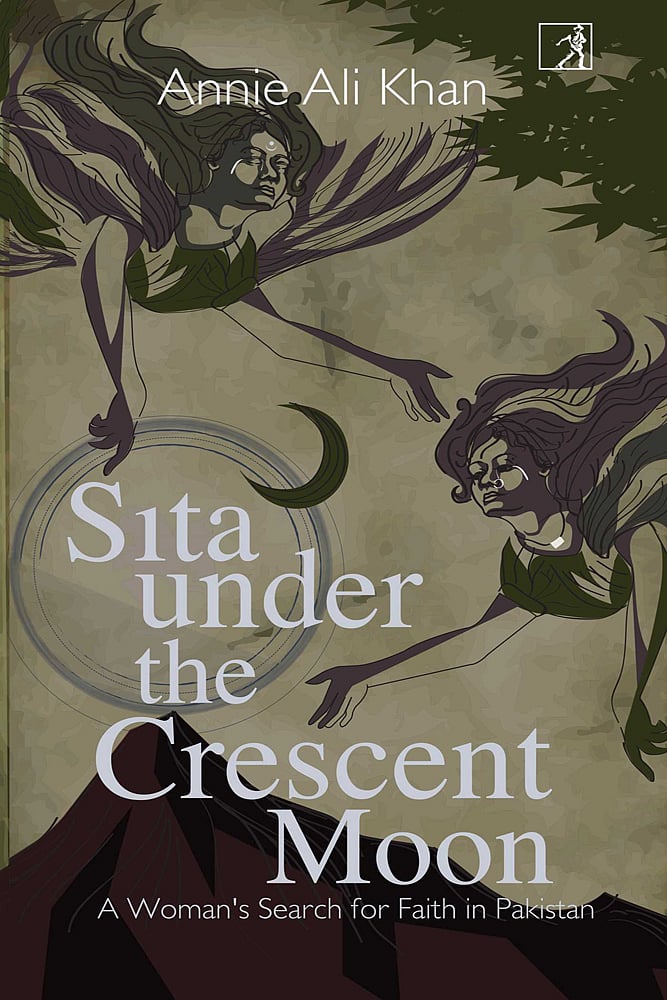

Shortly before her sudden demise in the Karachi apartment where she had lived alone, Annie Ali Khan had completed the first draft of a manuscript on journeys into the interiors of the Sindh and Balochistan provinces of Pakistan, during which she had travelled with and searched for women and their stories of devotion. Published posthumously, Sita under the Crescent Moon concerns itself with a uniquely women-centric tapestry of belief, within which are contained dargahs, serpent-deities, the goddess Durga who is the Nani Pir of a volcano in Hinglaj, immolated women who became reconfigured as guardian spirits known as satiyaan, ceremonies of smoke and flowers, rapturous dancing, enchanted trees and mythical creatures, magic curses, miracles, and myriad elements of ‘[f]aith and spirit lying outside the realm of the vague yet over-ruling idea of Islam [that]came to be referred to as Hindu’—and beyond.

From the ecstasy of the dhamaal, in which dance and prayer transport the body and mind to another state, to the difficulties of practical life as women who carry the agony of being in the sway of the supernatural, Sita under the Crescent Moon covers an impressive range of practice and experience, in addition to lore. The narrative is always compassionate (‘Most women came to Gulshan [a shrine-keeper] for love or for marriage. All came to save their lives.’) and rendered without bias. It is clear Khan has met each of her subjects on their own terms. What results is a vivid and mesmerising challenge to hegemonic narratives about women’s suffering, sacrifice and spirituality. The realities of Partition, organised religions and the author’s own cosmopolitanism try to draw the narrative into conventional lexes but ultimately submit to the force of the subject. This book maps a realm which is entirely its own, populated by ordinary women whose lives are coxswained by untameable divinity. It has ‘a geography known only to women, for women.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In the intricacies of this kind of faith, what is taboo in the world at large weaves in and out of acceptance. Women ask to be brushed between the legs and on the breasts with holy peacock feathers so they will be blessed with sexual charisma, or they request remedies to strengthen their bodies for sex. Dhamaals and shrines are redolent with the scent of hashish, yet on one bus pilgrimage, women shout at smokers and call other women whores. A menstruating, abandoned woman is dragged away leaving a trail of blood and gossip. The devout Zahida, one of the most striking profiles in the book, speaks with ease of her love for women. The world that Khan paints is composed of many sub-worlds; and it too is subsumed within this meta-world to which this book brings these stories, whether they are accepted here or not.

‘The goddess on fire now lived in the seaport of Karachi—lived because truth has a life of its own,’ Khan describes a shrine’s provenance early in the book. Later, an unnamed elderly woman says at a prayer circle in a bedroom somewhere near the city of Thatta in Pakistan’s Sindh province, ‘You can choose to believe or you can look away, it all depends on how much of truth your heart can bear.’

As though in honour of this being an incomplete work, the book almost lovingly makes its imperfection visible. Spelling and grammatical errors appear too often for the reading eye to miss, there are parts which another draft would have more finely honed or elucidated, and even the text is laid out in a stark sans serif font that resembles a proofreading document. In their way, these come together as a sentimental gesture towards both the subject and the author’s memory. They remind the reader that despite Sita under the Crescent Moon’s intensity and importance, this is still a tragic truncation, and that beneath the finality of its form are still-lingering spirits and silences.