The Womb of the Earth

NILACHAL HILL IN Guwahati rises about 560 feet from its surroundings and casts a vast shadow to the south and east in the evening. At dawn, seen from the middle of the Brahmaputra to its north, the hill appears like a citadel stretching interminably along the riverbank. On one of its summits, the most significant Mother Goddess temple in the subcontinent has cast an even larger influence over devotees. Kamakhya is at once a fertility goddess and an anchor of tantric beliefs. Mahamaya, as one of the many names her devotees use to address her—the goddess of illusion and deep magic, appeased with blood sacrifice. Yet she is also a manifestation of formidable creative forces and the recipient of a diverse range of contemplational and devotional rituals, worship and practices. But in considering the complex ideas of sacred geography, scriptures, rituals and personal faith that surround her, the exceptional nature of the goddess and her temple often passes unremarked.

Towards the end of his life, the Axomiya polymath Banikanta Kakati addressed this puzzle: the temple notwithstanding, Shakti worship is actually uncommon in the Brahmaputra Valley, and has historically been so. It is true that, through the usual osmosis of beliefs caused by the presence of a major pilgrimage site and more recent cultural influences, there are exclusively goddess worshippers in Lower or Western Assam, particularly among the upper castes. But they are far outnumbered by Shaivites and Vaishnavites. In his own time, Kakati knew there were more Shiva temples in the region than that of any other deity, while the egalitarian, idol-rejecting Vaishnavism of the great medieval scholar Sankaradeva has a deep cultural presence that has shaped Axomiya self-identity, literature and music far more than any other religious tradition has. Kamakhya’s existence in the valley, and its enduring importance within Hinduism, is therefore exceptional in the Axomiya context.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

In 1948, Kakati published The Mother Goddess Kamakhya, which pieces together the story of a temple and the inferred political processes that willed it into existence.

He found the beginnings of the explanation in the Kalika Purana, one of the minor Puranas, most of it composed in Assam sometime before the eleventh century CE. A Shakta scripture, its philosophical ambitions are rather modest, but it attempts to bring together the major Hindu goddesses into a cohesive singularity around the idea of Kamakhya. And it has this story.

‘A man named Naraka from Mithila led an expedition to colonise what was then the ‘anarya’ Brahmaputra Valley, whose original inhabitants (called Kiratas by Puranic Hindus; an umbrella term for the many native tribes of eastern India and the lower Himalayas) worshipped a form of Shiva. Naraka’s religious guide—the text says this was Vishnu himself—told him to settle Brahmins in the valley, promote the worship of the Goddess Kamakhya and deny patronage to other gods, including Shiva. The Kiratas withdrew to the ‘eastern sea’ and Shaivism went underground.’

But it lingered, and the Shaivite remnants decided to bring the settlers’ leader over to their side. Bana, ruler of a neighbouring kingdom and a formidable Shaivite, struck up friendship with Naraka and influenced him to abandon both goddess worship and patronage of dwijas (literally, twice-born, ie ‘upper’ castes). Palace politics followed, and the story then introduces the familiar narrative device of an upset ascetic’s curse (in this case, the sage Vashistha). Naraka is finally slain by Vishnu in the form of Krishna. In his last moments, the fallen hero from Mithila sees Kamakhya on the battlefield, fighting in the form of Kali by the side of Krishna.

Naraka, the figure if not precisely this version of him, appears in numerous texts, including some of the later strands of the Mahabharata. In his afterlife he has found some kind of endurance—the mighty hill range south of Nilachal is named after him and has traditionally been accorded occult significance by tantric adepts. At least three major dynasties in medieval Assam claimed descent from him. For most Indians, he would be familiar for lending his name to Naraka Chaturdashi, the second day of Diwali, commemorating the night when the man, given asuric characteristics by various scriptures, made his last stand in his fortress against his disavowed deities. Medieval scriptures have rather drastic solutions for apostasy, particularly when the apostate is a fallen hero and an oath-breaker.

Here the wronged god is Vishnu, indicating the composers of the Kalika Purana had Vaishnavite sympathies or were writing for a monarch who did. The Shaivite version of Kamakhya’s foundational story is the better-known episode, found in several puranic iterations, involving the self-immolation of the Goddess Sati, and Shiva’s tandava.

Sati, wife of Shiva, was outraged when her father, King Daksha, held a great sacrifice but did not invite them. Confronting her father, and humiliated by him, she immolated herself in the sacrificial fire.

Shiva then picked up her body and began his dance of destruction. With the whole of creation in peril, the gods asked Vishnu to intervene, and the divine Sudarshan discus cut Sati’s body into several pieces. The places on earth where these fell became Shakti Peethas, of which eighteen are major Mother Goddess pilgrimage sites. Sati’s yoni fell at the site of Kamakhya, becoming the foremost Shakti Peetha.

Through such layers of myth, minor puranas like Kalika provide clues for larger historical and political processes. In Naraka’s story we catch a glimpse of large-scale events witnessed elsewhere in the subcontinent’s many peripheries: settlement from Aryavarta, the conflation of indigenous belief systems with emerging ideas of Shaivism, the denial of patronage to Brahmins and official deities leading to conflict among settler factions, and finally, the triumphant return of dwija-sanctioned religious practices, although only in the limited geography of Pragjyotishpura, capital city of the Kamarupa kingdom in myth and eventually, recorded history.

THE THREE OUTER chambers of the temple have a distinct, different roof, in the form of a barrel vault, a design which the locals call ‘tortoise-backed’, and students of Indian temple architecture would recognise as ‘hastipristha’. Although these design choices and stylistic combinations became remarkably influential in the construction of other temples in the valley, giving rise to what is called Nilachal architecture, the barrel vault is of a much more venerable and unexpected lineage. Its original template can be found in the Parasurameshwara Temple in Bhubaneshwar, dating to the middle of the eighth century CE. Through a circuitous route, one of the oldest surviving elements of temple architecture in eastern India had made its way to Kamakhya through construction projects in Bengal. Thus both iconoclasm and architecture, vandalism and construction run as common threads through Bengal, Assam and Odisha during this period. Coincidentally, this type of barrel vault is also resilient to seismic stresses, as the later history of Assam shows.

Nor were these influences the only imports from the west. Of the many priestly families which live in the temple complex today, several are Parbatiya Gosains, descended from a renowned Shakta seer of Bengal who was invited and given stewardship of the temple by Ahom king Siba Singha in the eighteenth century. A hundred and twenty years after it was rebuilt, Megha Mukdam’s brick-and-stone temple still stood, but the valley was on the brink of devastation.

The Koch kingdom had fragmented into two, and the contestants were now the Mughals and the Ahoms. In 1671, the Ahoms defeated the Mughals on the river next to Nilachal and recaptured the temple complex. Despite its excellent strategic location, the hilltop had never been fortified, with the Ahom fort located at Itakhuli, upstream, where downtown Guwahati begins today. The victorious Ahoms found the temple complex desecrated, although not with the finality shown by earlier invaders.

At that moment, in the culmination of a definitive war to determine Assam’s sovereignty, the Ahoms could have chosen to leave their imprimatur on the temple in a comprehensive manner. They did have the resources and talent for this. Ahom monumental architecture had acquired definite forms by then and can be seen in some remarkable examples in Upper Assam from the turn of that century.

However, the Ahoms chose a major repair project instead, restoring some damaged sculptures and the newer shikhara and barrel vault, as well as the massive walls and two gates which surround the temple. In doing this they ignored the temptation, to which even modern governments are known to succumb, of leaving political legacies through temple reconstruction. Perhaps they recognised that, in its essence, Kamakhya is about what lies in the garbha griha, and not in the mutable structure which encloses it.

The visitor today will find the clearest iteration of Ahom architecture in the doors of the nritya mandapa, while in its form and structure, the temple remains what Megha Mukdam had intended it to be.

THE SHIKHARA ADMITS no light. There are no gaps or even loopholes in the plinth or walls, nor are there any windows or skylights, however modest, on the roof over the garbha griha. Descending about six feet from the entrance of the garbha griha, the devotee is enveloped in an amniotic darkness, facing the opening in the rock while enclosed by the towering vault of the shikhara. The effect can be described as an approximation of a womb, which may not be coincidental. In this, the physical core of Kamakhya, one may finally understand why, of all the major sects of Hinduism as practiced today, the sacred geography of Shakti worship is the most rooted in the natural features of the site rather than in the architectural features of the temple.

This sense of enclosure continues in the three outer chambers, particularly the nritya mandapa, which in most medieval north Indian temples is a pillared space without walls. But in the Kamakhya Temple, each succeeding chamber is darker than the preceding one, culminating in the garbha griha.

Kamakhya is therefore built on two levels, the higher comprising the three outer chambers, and the lower comprising the garbha griha. The earliest temple builders seem to have chosen this plan, partly because excavating the area near the garbha griha to make the foundations level with it would have meant chipping away at the rock layer from which the stream emerges.

Outside the temple, one can approach a paved circumambulation route or pradakshinapatha which is approximately eight feet lower than the surrounding courtyard and level with the foundation blocks. This route is surrounded by a wall which has striking and stylised figures of ganas inlaid on it.

It is customary for devotees to offer sacrificial chickens, pigeons, goats and buffaloes and less commonly, ducks to the goddess. Animal sacrifice has been traditionally associated with Devi worship in the subcontinent. While there are occasional controversies about this, the practice at Kamakhya is largely undertaken today in much the same manner as it would have been in the late medieval period.

Human sacrifice is a much more problematic legacy. There is some evidence that it was practised at the temple in medieval times and at least till the earliest part of the colonial period, but not predominantly so. Stronger associations can be found in farther corners of the region, in places over which the last tides of Hinduism washed. A little more than 550 km east of Guwahati, on the outskirts of the town of Sadiya, was the fourteenth century temple of Tamreshwari, after the beautiful roof made of beaten tamra or copper, where an aspect of Kali was worshipped. It was more popular among Axomiya, Deori and other communities as Kesa Khaiti, or the ‘goddess who eats raw meat’, because this was offered as prasad there. Along its western wall was a designated place for human sacrifice. The original temple no longer exists, being submerged by a nearby river in the 1950s, and the current temple nearby has less objectionable sacrifices and practices.

The occult and tantric, however, are integral aspects of Kamakhya and all the other goddess temples in the complex atop Nilachal. Adepts and novices journey from far corners of India, particularly during the Axomiya month of Ahaar, in the middle of June. This is the time of the Ambubachi Mela, when the temple is closed for three days because the goddess menstruates. On the fourth day, worship resumes. One may find the occasional tantric adept camped on the temple grounds during the entire month, and families of Shaktas as well. Of the approximately four million visitors to the temple each year, a substantial number, particularly the more distant ones, arrive during Ambubachi, some at the culmination of a countrywide pilgrimage of the major Shakti Peethas.

Devi worship, in its doctrines, rituals, scriptures and practices, covers a diverse range of faith-based positions, from the everyday worship of lay believers to the rigorous observances and arcana of tantric adepts. Its roots go far back in time to layers of indigenous and folk beliefs which have since been given formality while being subsumed by caste Hindu belief systems, even as the original believers were pushed to the ‘eastern sea’ of the mainstream mindspace. These rooted positions have proven curiously resistant to change and the influence of reformist tendencies, just as the ancient sites of this worship anchor and outlast the physical structures that have been built and rebuilt over them. But in its strong bonds to the earth, to the vitality of natural processes, and even to the idea of blood sacrifice, through parallel symbolisms of water and blood, creation and death, goddess worship touches some of the more primeval and atavistic chords in the network of religious ideas that together comprise what is called Hinduism. Kamakhya represents these extraordinarily vital bonds in many unique ways.

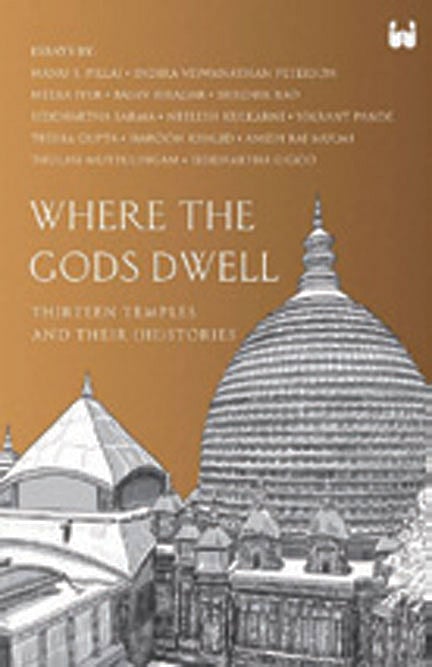

(This is an edited excerpt from Siddhartha Sarma’s book Where the Gods Dwell: Thirteen Temples and Their Hi(Stories) releasing on November 15th, 2021)