The Sixth Sense

GOLDEN AGE detective stories offered above all a pleasing orderliness—a way of seeing ghastly disruptions restored to equilibrium with the soothing predictability of ritual, said Paul Grimstad. This is certainly true of two of the books reviewed this week. Two detectives of different nationalities, Japanese and Swedish, written by two authors (Scottish and Japanese), and yet, common elements link these two mysteries. Both are told in a simple style through vignettes, and through a telling detail that illuminates the sweet intimacy of relationships.

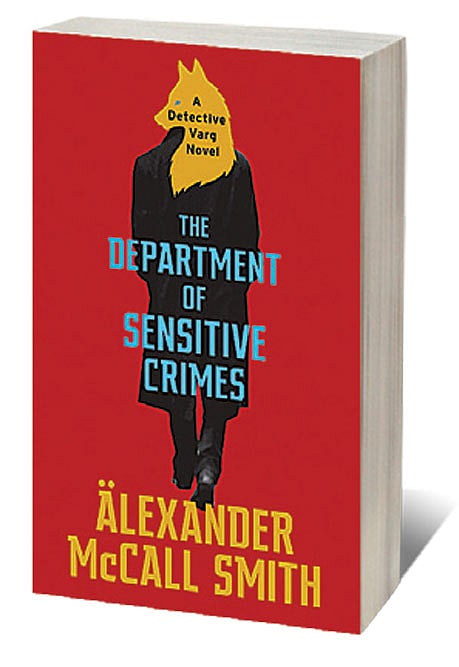

Our beloved Alexander McCall Smith has started a mystery series set in Sweden. His detective Ulf Varg, translated as ‘wolf wolf’ in Danish and Swedish, is a 40-something head of Malmo’s Department of Sensitive Crimes, abandoned by his wife, lives with a hearing impaired dog, not very solitary, likes his colleagues—fishing mad Eric, workaholic Carl, and the beautiful much-married Anna for whom he cherishes unresolved feelings. But true to the spirit of Scandi Blanc, our detective does not act on it. He wants to be honourable.

‘You like her, don’t you,’ said Carl. Ulf nodded. ‘I like her but I can’t like her, if you see what I mean.’ Carl looked away…’ What are you going to do about it?’ ‘Nothing,’ said Ulf. ‘It can’t be.’ ‘I can see that,’ said Carl. He leaned forward and put his hand on Ulf’s shoulder. ‘Let me tell you something Ulf. You are the best, kindest, funniest person I know. You are also the most truthful.’

And that, in short, is our hero who has to solve sensitive crimes such as why would someone stab a man in the back of the knee? What do you make of a complaint by a friend about her best friend—that the best friend may have bumped off her boyfriend? How to tackle a possible case of lycanthropy (mythical transformation of a person into a wolf) especially when it is connected to your boss’s relative?

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Ulf is a thinking man’s detective whose mind wanders down charming avenues such as travel. Ulf has always gone north, never south. And then we learn about all the northern places he has visited including three glorious weeks in Nepal with his ex-wife. Ulf is aided in his investigation by Anna and also by a policeman, Blomquist, who has applied unsuccessfully to transfer to the plain clothes department. A walking encyclopaedia of medical factoids such as the problem with sunblock, Blomquist irritates good natured Ulf but is allowed to tag along anyway.

Ulf Varg is a detective with souls in his care. ‘He thought souls because that old fashioned word said so much more than the word person. A soul was something more than that—a soul had feelings and ambitions and private tragedies. A soul weighed more than something that was not a soul.’

That sums up his attitude to crimes, to criminals and to the victims. So refreshingly different from the Scandi noir serial- killer books. Pick it up and read it immediately.

Keigo Higashino is one hell of a chameleon. In each book he uses a different set of writing tools to craft the mysteries. Newcomer takes us deep into Japanese urban society. Kaga, the homicide detective has been demoted from Tokyo Police to the quieter neighbourhood of Nihonbashi. A woman is strangled in her apartment, and Kaga is put on the job. But the telling of the investigation is arranged in a series of charming vignettes connected to the murder through a pile of clues such as sweet pastries containing wasabi mustard that were delivered to the murdered woman on the day she died, chopsticks, a wooden spinning top, scissors, and a shrine. As Kaga tracks each clue, he (and we, readers) also dip a finger into the emotional cauldron of the shopkeepers’ personal lives—the mother- in-law and daughter-in-law tussles, parent-child face off, infidelity, a falling out with a friend, and so on. Before long, it seems like almost everyone— restaurant owners, shop assistants, waitresses, runners, insurance agents—in the busy Tokyo street has a motive for the murder. Kaga is an eccentric Columbo-like character who notices details, and manages somehow to set right all that is wrong in the lives of the ordinary folk in the neighbourhood. You get a great glimpse into everyday life in Japan. Higashino’s inspired and masterful ability to toy with the mystery genre is breathtaking. Here, he combines a short story method with the traditional Agatha Christie-like mystery novel—we readers view the scene and the characters first before the main detective enters the picture. A lovely feel-good novel that leaves you, like the Scandi blanc one, in a good mood with humankind.

Sam Bourne’s thriller, To Kill the Truth, starts with an interesting premise. What if someone decided to erase history? What if they did it by burning the major national libraries in the world? What if the online data was also simultaneously wiped out? Don’t know, don’t care, nothing happened, nothing’s there —the chant of the supporters of a William Keane, a charismatic southerner, a self-styled historian who had become a hero to the American far right, currently involved in a court case where he had sued an African American historian for calling him a slavery denier. His case—black people had never been slaves in America. As libraries burn in India, UK, France and elsewhere, the only person who can stop it is former White House negotiator, Maggie Costello. As she tracks the kingpin to a group of acolytes around a young William Keane, she finds herself facing arrest and charges of threatening the President. The book is well researched and well written, and the suspense snakes through all the way down the spine. Maggie is a feisty protagonist with a dark secret from her childhood. With the help of a former boyfriend, an Israeli documentary filmmaker, she puts the pieces of the jigsaw back together. Sam Bourne’s journalistic credentials— it is the pseudonym of Jonathan Freedland of the Guardian—ensure a solidly researched book reminiscent of a Frederick Forsyth. While the denouement is not surprising, it is satisfying enough for a reader because of the sound narrative which presents difficult ideological explanations simply without losing the complexity of the issues. Well worth a read.

Lucy Foley’s The Hunting Party is a different kind of mystery- thriller. Less information, more character-driven, but also about an obsession. A group of Oxford friends—all couples except one—go on an annual New Year’s Eve outing to a remote Scottish winter highland lodge. They are the only guests there apart from an Icelandic couple who appear and disappear quite quickly. It is a classic country house murder mystery narrated from six points of view. The new Lodge is managed by a thirty- something woman running from her own ghosts and a gamekeeper, an ex-Marine with his own traumas. One of the friends turns up dead. We don’t know who it is until three-quarters of the way through the book. All we know is the stereotypes— the attractive and popular girl with the handsome husband, the mousy best friend, the eager- to-please girlfriend, a newcomer to the group, the happy couple with a baby (who barely register with the reader), and the gay couple. The characters themselves are not particularly interesting, and there seems to be nothing in their shared past that could drive one of them to murder. The landscape plays a role, and here there is a difference between how the gamekeeper sees the landscape ‘harsh, skeletal lines of the land’, ‘granite peeking like old bone through the rust red fuzz of heather’, and how the city slickers see it—raw, untouched by human hand, old ruin, bleak and brutal, and so on. For the Londoners, none of the landscape comes alive—it is like viewing scenery from a train window without feeling any connection to it. Much like the book, a breezy airplane read but with an unsatisfying ending for a mystery aficionado.