The Scarred Megapolis

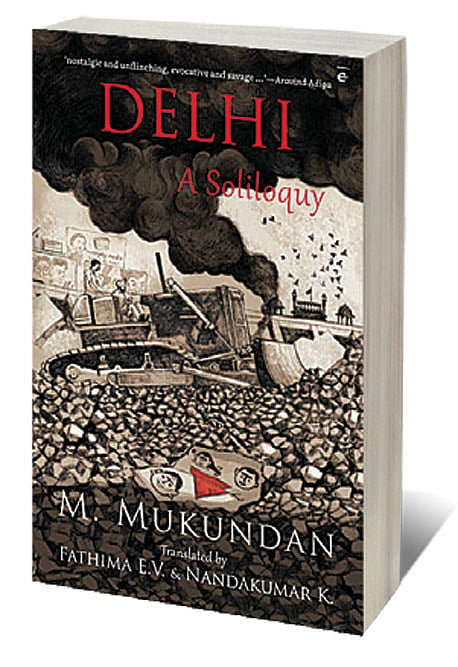

A SOLILOQUY, AS ANY professor of literature would tell us, is a monologue delivered to oneself; it involves the act of speaking one’s thoughts aloud when one has no one to address them to. For most of the 538 pages of M Mukundan’s novel Delhi: A Soliloquy, I was left wondering why the term had been used in his subtitle, until at the very end its relevance became apparent.

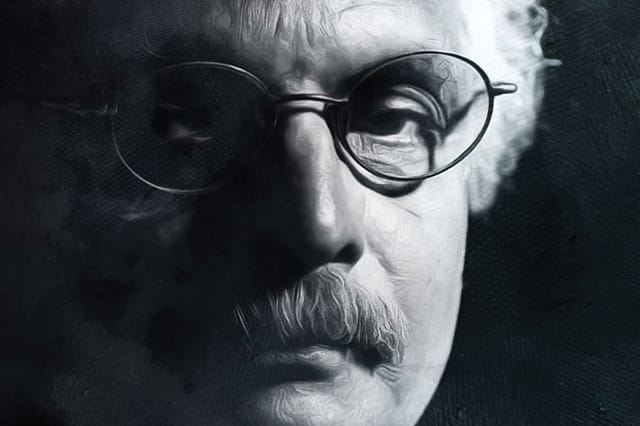

This is the kind of subtlety one must be prepared for in reading a book by the eminent Kerala writer, whose 2011 Malayalam novel, Delhi Gaathakal (Delhi Tales), has just emerged in a long-awaited English translation as Delhi: A Soliloquy. Mukundan is at the very forefront of Kerala letters today. He is better known as the illustrious son of Mahe, the only French colony in Kerala, raised by the Mayyazhi, the river that featured prominently in his classic early novel, Mayyazhipuzhayude Theerangalil (On the Banks of the Mayyazhi), which won numerous literary awards and established him in the front rank of contemporary Malayalam writers. But this novel takes us to the opposite end of the country, abandoning the lush greenery of Mahe for the arid and soulless streets of the nation’s capital.

The novel opens in 1959, with the protagonist, 20-year-old Sahadevan, arriving by train in Delhi from Kerala, in pursuit of an elusive future. ‘It’s in Delhi that your life will begin,’ he tells himself. ‘As soon as you reach Delhi, you should go to Nehru’s house and meet him,’ his mother urges him as he is about to embark on a journey to the capital. ‘But don’t go there wearing a dhoti. Go only after you get trousers.’ This telling bit of advice encapsulates much of the mystery and allure of Delhi in those days, the sense of infinite possibilities before an ever-expanding horizon, where a young man could go in search of a future. (And decidedly too different from Kerala, too modern and important, for the modest mundu or Kerala dhoti.)

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

But Sahadevan is a somewhat aimless young man, constantly engaged in conversations with himself, seemingly unmotivated to succeed, to make money, develop a career, acquire a wife or establish a permanent home. As he drifts across the city observing its changes and its cataclysms,

disillusionment strikes early:

‘If material comforts had been the purpose of life, by now Sahadevan would have gone back to Kerala. The only two problems there were unemployment and poverty. And even if there was poverty, there was cleanliness and hygiene. Even if there was hunger, people were socially conscious. He saw nothing of that in Delhi.’

Sahadevan’s story of Delhi is that of an observer of the city’s turbulent evolution for nearly four decades, from an overgrown provincial city overcome by refugees and stark poverty, acquiring the trappings of authority as the national capital, to the gleaming prosperity of today, mirrored in the transformation of Sahadevan’s first employer, Gulshan Wadhwa, from a make-ends-meet forwarding agent to a millionaire who can afford to give one of his daughters a Mercedes-Benz as a dowry. On the way the novel is punctuated by the major historical events that shaped the author’s experience of the city’s evolution: the war with China in 1962, the Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971, Emergency of 1975 and the Sikh riots of 1984.

But it is above all the story of the Malayali community of Delhi, the struggling professionals among them and the way in which they are impacted by these events. Sahadevan benefits at the start from the help of the communist trade unionist Shreedharanunni, who hangs a portrait of Chou En-lai on his wall, his wife Devi and young children Sathyanathan and Vidya, whom Sahadevan regards as his younger siblings. But his Delhi expands to include a host of other memorable Malayalis (and, inevitably, a handful of non-Malayalis too, but only in supporting roles).

As a chronicler of Delhi, Mukundan is interested in the unfortunates, not the success stories: there are references to a Georgekutty who has made it big, but he is not a character the reader gets to know. The Krishna Menons or Unnikrishnans of politics, the KPS Menons and TKA Nairs of bureaucracy, the VK Madhavan Kuttys and BG Vergheses of journalism, the George Muthoots or Rajan Pillais of business—the big Malayali names most refer to when thinking of Keralites in the national capital—are neither mentioned nor fictionally reinvented. Theirs are not the stories that interest Mukundan.

Instead there are the crusading journalist Kunhikrishnan and his unhappy wife Lalitha who yearns for a child her husband cannot give her; the eccentric artist Vasudeva Panicker, who wanders about indifferent to all social or personal niceties but is brimming with a precocious talent; the displaced young Rosakutty, who has reinvented herself as the call-girl Rosily in order to make enough money to go home and marry her beloved in Kerala; the visiting school-teacher Abdulnissar, a widower who is wooing a sister of Sahadevan’s that our protagonist has been unable to raise enough money for (to ‘get her married’); the bespectacled scholar-activist Janakikutty, daughter of a firebrand revolutionary who is on the run during Emergency; the widowed Devi ekeing out her existence as a peon in the Central Secretariat, her days circumscribed by her routine chores at work or for the children she must raise amid deprivation.

Mukundan’s strength is as a great teller of stories. He inveigles you into the lives of his characters with his eye for the telling detail. Mukundan feelingly portrays the concerns and struggles of the ordinary, lower-middle-class characters, recounting their struggles and yearnings in painful detail. The college-going girl whose footwear is tattered and frequently mended, the office-goer wearing the same shirt day after day because that is all he can afford, the Sikh carpenter who cannot save enough for a dowry for his daughters, the pavement barber whose livelihood is destroyed in an Emergency cleanup drive, the young woman whose widowhood and poverty lead men to assume she must be available for the night—all these and more come alive through the pages of Delhi: A Soliloquy.

The authorial tone is always understated: there is no melodramatic flourish even when events of great dramatic import are being narrated. A chronic consciousness of the fragility of life pervades the novel. Random deaths occur frequently in its pages: a large number of characters, both minor and major, die in the book, but many do so offstage, the details of their often grisly endings omitted by the narrator.

STILL, THIS IS not a novel that the Delhi tourism department will want to promote. It shares in unsparing detail the seamy side of life in the city, the smells, the dust and dirt, the omnipresent excreta, the injustices and the daily horrors that make the very challenge of survival for the city’s residents an ordeal. Life in Mukundan’s Delhi is nasty, brutish and squalid, fragile and easily disrupted in eruptions of rage and violence.

‘25 June 1975. That was when the age of nightmares began.’ Nearly 100 of the book’s 536 pages of narrative are devoted to Emergency, in searing and unsparing prose that graphically details the atrocities of that era. A 62-year-old man dragged off to a vasectomy camp is left to bleed after a botched operation and flung on the road. As the blood seeps from between his legs, the author caustically writes: ‘The Emergency had given the consumptive old man the gift of menstruation.’ For one key character in the novel, as for thousands in the nation’s capital, ‘the Emergency inside her mind still continued’ long after the official state of siege was lifted.

The savagery of the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 is also chronicled in heart-rending events that directly affect some of the key characters in the book. As two survivors walk hand-in-hand through the smouldering ruins, ‘with the stench of the dead in their nostrils’, drawing strength from each other, ‘Delhi appeared to them like a huge painting made with blood.’

The portrait of the city and the Malayalis there clearly reflect the author’s own experience of the city’s transformation from a place of wheat and cauliflower fields into the scarred megapolis of today. It was, after all, in Delhi that Mukundan, who arrived in the capital at the age of 21 just three years after his fictional protagonist, in 1962, found his vocation as a novelist. His recollections of the tortuous train journeys of that era, which resulted in the passengers arriving covered in soot from the coal-fired steam engines of the Madras Mail and the Grand Trunk Express, find echoes in his character’s accounts.

As a young ‘marunadan Malayali’, Mukundan had a long innings at the French Embassy as a locally recruited cultural attaché, writing after office-hours and establishing himself as a pioneer of modernism in Malayalam literature. It was while based in Delhi that he authored a dozen novels, including the celebrated Daivathinte Vikrithikal (God’s Mischief, 1989), and won multiple awards including the Ezhuthachan Puraskaram, the Kerala government’s highest literary honour. After his retirement from the French Embassy he led the Kerala Sahitya Akademi before finally reliving his Delhi years in this book.

Delhi: A Soliloquy is undoubtedly a considerable book, its physical heft justified by the weight of its ambitions.

The translation by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K is competent and unobtrusive: I mean it as a compliment when I say the novel does not read like a translation. This does mean, however, that literary flourishes are few and far between: while the prose flows fluidly, it does not sing in English as it would in Malayalam.

As a portrait of the city over four eventful decades, however—and of the diaspora Malayali community within it—Delhi: A Soliloquy has no equals. I commend this English-language version to non-Malayalam-educated readers everywhere: a compelling, absorbing read by a master storyteller at the height of his powers.