The Missing Pieces

The last decade has been a tumultuous one for the Indian economy. Despite the early narrative of India emerging unscathed from the global financial crisis of 2008, the ensuing decade has confirmed that India is still feeling the second and third degree effects of this crisis, which has significantly dampened prospects for both economic growth and private investment.

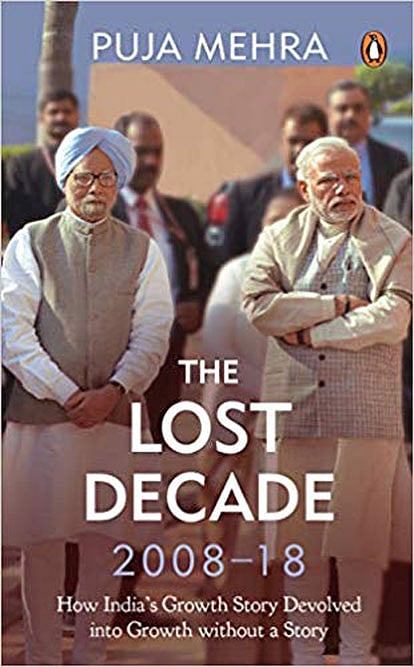

In The Lost Decade, Mehra establishes an almost omniscient behind-the-scenes account of some of the major actors who were responsible for steering the Indian economy over the course of the past decade. The cast of characters in this tragedy includes prime ministers, finance ministers, major politicians, leading financial bureaucrats, RBI governors and more. In many ways, this book reads like an anti-hagiography, a scathing indictment of the myopia and petty narcissisms of the men who were responsible for steering the Indian economy, but failed to do so rather spectacularly. In particular, Pranab Mukherjee’s documented failures, both personal and administrative, are exceptionally egregious.

But Mehra leaves no prisoners in this book; it is not simply the UPA II and its policy paralysis that are taken into account. The second half of this book focuses on the first Modi government. The shaky economic inheritance is acknowledged, but the repeated mistakes through complicating and diluting GST, demonetisation, waiting to address the NPA crisis, and poor relationship management with the RBI makes it clear that there was plenty of incompetence across all parties.

In fact, one of the most refreshing parts of this book is its fearless holding to account of people at all levels of power. Frequently in macroeconomic narratives, authors either hide behind jargon and technical arguments, or they oversimplify arguments blaming one institution while exonerating others. Mehra does neither of these things. Her book is not a litany of complaints against politicians and bureaucrats. Instead, it is an immaculately sourced, fly-on-the-wall account of how those who roam the corridors of power, both politicians and bureaucrats, were unable to rise above their political scheming and fiscal myopia to think about the Indian economy more broadly.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

One of the questions that Mehra’s book does raise is about the value of independent economic expertise. Both governments consistently went against expert opinion (both internal and external) during their tenures, and in the process managed to exacerbate India’s economic problems. But both governments also had their own stables of ‘experts’ who were willing to twist their academic integrity beyond all reasonable bounds to justify incumbent policy. Is it truly possible to be an independent expert and be influential within government? Whether it is the hard-headedness of politicians, poor communication by experts, or their outright politicisation, it is clear that deep suspicion and concerted undermining of notions of expertise have become part of our political reality.

Another, more practical, question that emerges from Mehra’s book is the capacity of the Indian state to understand, manage and regulate India’s complicated multi-tiered economy. Whether it is the RBI’s regulatory failures related to the NPA crisis, the banking system’s failures related to demonetisation, or the tax bureaucracy’s failures related to GST rollout, much of our ‘steel frame’ seems to be stuck in its erstwhile dirigiste avatar, when it needs to slowly morph into more of a supervisory night watchman role. Whether these are sins of omission or commission, there is clearly a desperate need to understand the ever more frequent failings of India’s economic bureaucracies and how policies and roles can be made with a realistic assessment of their capabilities. Rolling out policies hastily without adequate bureaucratic preparation has hurt the current government more than once at this point.

The most impressive part of Mehra’s book is its sourcing, which lends it an uncommon legitimacy. She manages to get senior politicians and bureaucrats on the record, she is able to narrate specific details about certain paragraphs being included in policy, and all of this comes together to remind one of Bob Woodward’s reporting on Watergate, or Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big To Fail. Journalistic books are frequently gossipy, full of poorly supported claims, and often lacking in technical detail. Mehra’s book does not suffer from any of these shortcomings. Her crisp, simple prose establishes both macroeconomic details and political context with equal skill, which is all the more admirable since this book contains not a single graph or figure. If one wants to understand the economic dysfunction of India over the last ten years, this is a great place to start.