Searching For Home

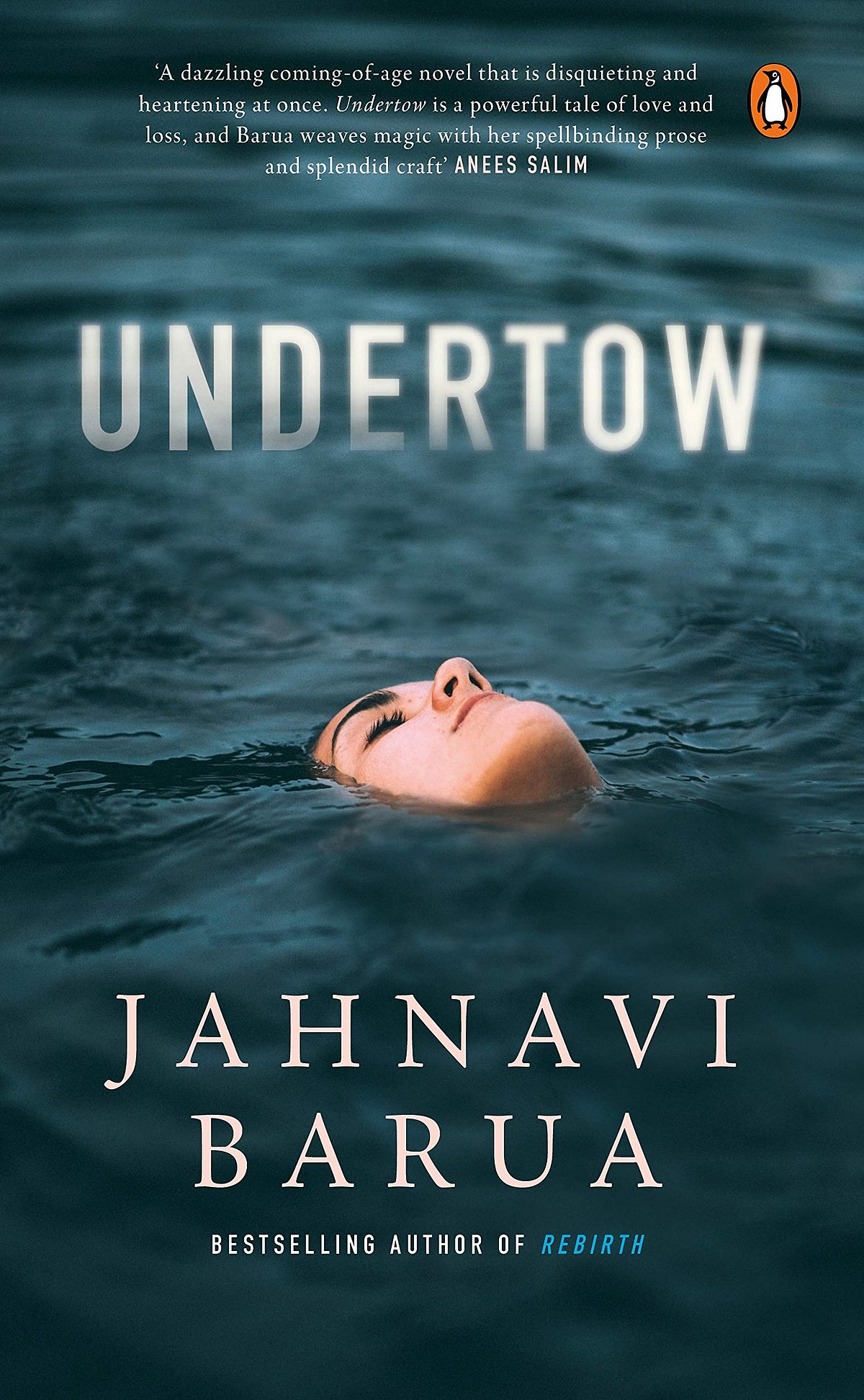

Is it possible for any of us to heal the ruptures of the past? Is it possible for the exile to go home again? Jahnavi Barua’s second novel, Undertow, grapples with these questions as it delves into the complexities of familial bonds. Twenty-five-year-old Loya sets off on a life-changing journey to Guwahati where her estranged grandfather, Torun Goswami, lives. Loya travels from Bengaluru to Assam without her mother Rukmini’s blessings, fortified by the hope that the reclusive Rukmini will eventually understand her reasons for reaching out to Torun and trying to rekindle their relationship.

Loya’s family history is complicated. Her parents, Rukmini and Alex, are divorced, and not in an amicable way. Her maternal grandparents, Torun and Usha, had banished Rukmini from their lives for marrying out of her community. Usha’s disapproval had been more intense and damning than Torun’s. Usha is an unforgiving parent who is ‘ferocious in her antagonism when she sensed the slightest resistance.’ The formidable Usha and Rukmini had never shared an ideal mother-daughter relationship to begin with. Rukmini’s affair with Alex had wrecked their bond completely.

Baruah expertly concocts the cocktail of mixed emotions Loya feels when she arrives at her grandfather’s yellow house, perched on a hill overlooking the River Brahmaputra. Loya’s ‘official’ reason for visiting Assam is to conduct research on the Asian Elephant for her thesis. Her head is set on the project, but her heart desperately wants to get to know her grandfather and the place he calls home. Loya and her mother have lived an isolated life, ‘shut away as if in an airtight cell’. Loya has never met her grandfather in person, never visited his home or heard from him in 25 years.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Undertow is steeped in an authentic sense of place. Baruah ties the personal lives of her characters to the explosive political churnings in Assam in both direct and subtle ways as the story unfolds. Right at the start of the novel, on the morning of the day of Rukmini’s wedding, the Assam Students’ Union calls for a bandh. Two young men whose ‘heads were split open in a police lathi charge,’ had died the previous night. The bride has to be driven to the ceremony with a police escort. Though Torun disapproves of Rukmini’s decision, he arranges for a police escort as a final favour to his daughter.

Baruah’s clear-eyed descriptions of Guwahati, beset by political strife, protests and bandhs that cripple day to day life as well as her lyrical ruminations on the landscape add texture and context to the human stories at the heart of the book. Baruah never allows readers to forget that these stories play out in a place where normal life is constantly disrupted and ‘people spilled out on to the streets in their thousands when summoned by the student leaders—the Boys, as they were affectionately called—to picket and demonstrate and protest, and stayed indoors with windows closed and lights out when ordered to by the same leaders.’

The yellow house that Tarun built in 1960, the year Rukmini was born, is also etched with deft strokes. Each character has a unique relationship with this old house overlooking the mighty Brahmaputra. Young Rukmini who grows up here and who is cruelly made persona non grata by her parents, Torun and Usha who share a happy married life within the four walls, the widowed Torun who longs for Usha’s presence as he wanders around his home, young Loya who hunts for fragments of her mother’s past in every room and every cupboard during her stay— all relate to the house in specific and individual ways.

Though there are some instances in the novel when political commentary tends to overwhelm the narrative, Undertow holds your attention as it traces the trajectory of lives ruptured by strife and mended by imperfect, human attempts to reconnect with people from across the divide.