Politics of Meat

Why have Brahmins not produced a Voltaire?’: BR Ambedkar opens his Preface to The Untouchables, a text which follows The Shudras—Who they were and how they came to be the Fourth Varna of the Indo-Aryan Society, with one of many perfunctory lines of interrogation. Some of them seek to explore, through socio-historic texts like Ashoka’s edicts, Manusmiriti, the Rig Veda, among others, the gravest conundrums of our times with beef-eating at its epicentre and the rise of Untouchability. A set of these questions, which The Untouchables seeks to answer are questions, which have not been ably, and fairly, put forth by a Brahmin Voltaire.

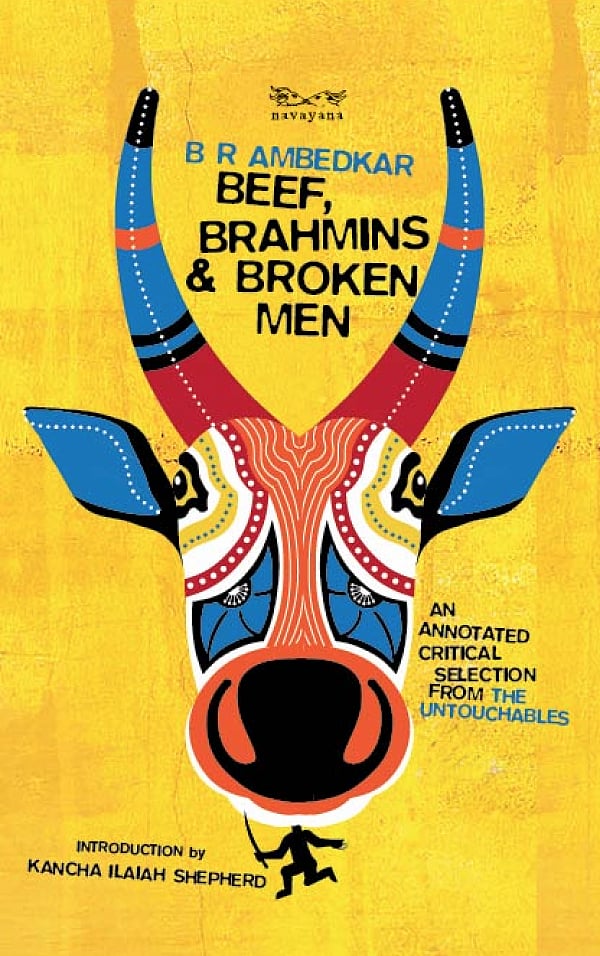

The selections from The Untouchables, which have been annotated with forensic precision by S Anand and Alex George in Beef, Brahmins & Broken Men seek to query the Gandhian incitation towards finding the ‘divine in the bovine’. In their introduction, titled ‘Fool’s Errand’, Anand and George set out an effective outline of their efforts with their annotations. These annotations seem successful for readers who are trained in the academic reading practice. As for the text’s non-academic suitors, the structure of the footnotes at the end of Dr Ambedkar’s selections is an architectural decision that jars and flails for attention and coherence. Given that both Anand and George admit to the fact that their interaction with The Untouchables trumps, in terms of word count, Dr Ambedkar’s selections, perhaps a separate essay after each chapter selected from The Untouchables, that shares a direct dialogic relation with Ambedkar would have made for a more welcome read.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Notwithstanding the essential structure of the book, the annotators rightly glorify and critique the chief author in fair measure. ‘The task has not been restricted to bring Ambedkar up to speed with contemporary academic findings,’ Anand and George write. ‘[W]e try and bring contemporary academic discourse up to speed with Ambedkar.’ Both annotators collaborate on finding where Ambedkar ‘errs’ in his readings, like his ‘flawed’ interpretation of Mricchakatika, in which Ambedkar finds anti-Buddhist bias when Anand and George find such bias absent from the play. Moreover, Anand and George do not desist from calling out Ambedkar on his ‘condescending and dismissive views on the subcontinent’s ‘aboriginal’ and ‘primitive’ tribes, quite in line with the views of the colonial authorities’.

When readers chance upon Ambedkar’s Preface, they will find provisions he has made for potential critics: ‘My critics should remember that we are dealing with an institution the origin which is lost in antiquity. The present attempt to explain the origin of Untouchability is not the same as writing history from texts which speak with certainty. It is a case of reconstructing history where there are no texts, and if there are, they have no direct bearing on the question.’

The crowning glory of the text, of course, is Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s essay that is stupendous in its multiple affects. It demands our practice of empathy. It evokes, in an eviscerating tone, the irony of banning beef-eating to secure one life through the often fatal violence of gau-rakshaks (cow-