Myopic Versions

THE KILLING OF ML Manchanda, an All India Radio official in May 1992, was a particularly gruesome incident even by the standards of terrorism in Punjab. It was not unusual for terrorists to segregate people travelling by public transport on the basis of their religion and then gun down the ‘unwanted’ group. But Manchanda’s case was unique in the blood-soaked annals of insurgency in the state. He was picked up from Patiala, where he worked, and beheaded. His head was thrown onto a busy road in Ambala, a neighbouring district in Haryana. The incident sent shockwaves across Punjab. By then, the state had been battling insurgency for 13 years and 1992 was one of the most violent years. Then, all of a sudden, the terrorists were gunned down one by one. Sporadic violence continued but, for all purposes, 1992 marked the terminus of Punjab’s journey of separatist violence that began in April 1979.

The insurgency in Punjab was relatively short and lasted a mere 13 years when compared with conflicts in Kashmir, Nagaland and leftist insurrections. It was also particularly intense and bloody: the last three years witnessed the most bloodshed. In 1992, 5,265 civilians, security personnel and terrorists died; a number higher than what was observed in Kashmir at the peak of the insurgency in 2000 and 2001. The intensity of killings in those years and the relatively short span of the conflict are yet to receive scholarly attention.

There is, however, no shortage of explanations for what happened. The received wisdom is that from 1973 to 1983, Punjab veered to an extreme political direction due to destructive competition between the two main parties, the Congress and the Akali Dal. Both sought to outdo each other in attracting the Sikh vote. This was not a direct pitch to voters as seen in India in recent years but creating a political platform that was more extreme than the other party. Sikhs were expected to follow the most radical one in a Pied Piper-like fashion. In the bargain, both Congress and the Akalis became irrelevant for more than a decade when the gun ruled Punjab. It was only after the death of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the man who gained most from this ruinous politics, that the state began limping to normalcy.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

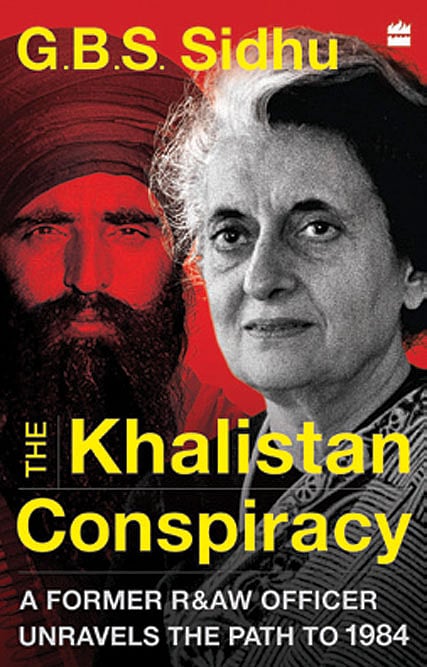

In The Khalistan Conspiracy: A Former R&AW Officer Unravels the Path to 1984 (Harper Collins; 296pages; Rs599), GBS Sidhu, a former Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) officer, sketches this story with an additional layer. He claims that the sequence of events, from the rise of Bhindranwale to the storming of the Golden Temple in June 1984, was part of a ‘conspiracy’ designed to secure political advantage for the Congress. In Sidhu’s version of the story, the sequence of events can be broken down into ‘Op-1’ and ‘Op-2’ that were to culminate in the 1985 parliamentary elections. But events followed a different course and in 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—supposedly the prime beneficiary of the plan—was assassinated by her guards.

It is a historical reality that politicians in Punjab—Zail Singh, his rival Darbara Singh and the Akalis—did play with fire in outbidding each other (Sidhu’s ‘Op-1’) but it strains credulity that national-level politicians could foresee, let alone plan, events with near-perfect foresight years in advance. The time horizon for Indian politicians of that age was considerably shorter; their ability to chart the treacherous politics of Punjab even less so. Even if one were to believe that a shadowy group operating out of Akbar Road in Delhi was plotting events, the author presents no direct evidence for that in the book. His heavy reliance on secondary sources to patch together his story, peppered with his conjectures and observations as India’s top spy in Canada in the course of his career, make for interesting reading but don’t add anything more to the literature on the subject.

This is the macro or ‘top down’ view of insurgency in Punjab. But there’s another part of the story that the scholar, bureaucrat and spy alike have ignored or, at the least, not paid attention to. Why did a part of Punjab’s population get swayed by what was clearly an unrealistic hope: a separate state of Khalistan? The fact remains that even after Operation Blue Star, by when the Union Government’s resolve in tackling terrorism was firm, recruitment to separatist ranks did not stop. There was a Pied Piper element at work.

Here is where the short-but-intense aspect of the conflict catches up with macro-level explanations for what happened. One can conjecture that extremism in Punjab’s politics did fuel terrorism but did not gain sufficient traction that prolonged insurgency became viable. In the spectrum that ranged from mere sympathy, to helping terrorists, to actually picking up a gun, a majority of Punjab’s population remained tethered at the sympathy end. But clearly some did turn to terrorism. It is this micro-level murkiness that allows suspension of disbelief for stories like the one Sidhu tells. Hence the enduring belief that terrorism could be neatly switched off by getting rid of men like Bhindranwale and, after his death, by crafting a suitable formula that could placate the preacher’s less violent and less extreme successors.

This is where Wajahat Habibullah picks up the thread in his expansive memoir My Years With Rajiv: Triumph And Tragedy (Westland; 356 pages; Rs799). His book is padded with historical backgrounds of various conflicts in Rajiv’s India but says little that is worthwhile. The one chapter (‘Discord and Accord’) that could have set the record straight on Kashmir, Punjab and Assam, blithely elides crucial details and the reader gets to know nothing. The Rajiv-Harchand Singh Longowal ‘accord’ is dismissed in a single paragraph while spending inordinate time on the background of the Punjab issue. What is left unsaid is how key provisions of the so-called accord, such as the transfer of Chandigarh, were not implemented after promising them. In other instances, inquiry commissions and judicial tribunals kicked the can down the road. The result was that separatist sentiment hardened further in Punjab and whatever little moderate leaders like Longowal could have done—which was not much to begin with—could not even be attempted. Longowal himself was gunned down in August 1985, a month after he signed the ‘accord’. His fault: he was ‘too moderate’ for the Punjab of that time. By then, educated Sikhs like the civil servant Dr Sohan Singh, who imagined a viable Khalistan on the basis of rational calculation, however erroneous that may have been, had no power. It was criminals and extortionists who roamed the plains of Punjab. Eliminating them was dirty work and took time. Conspiracy or no conspiracy, there was no other way to restore normalcy.

Memoirs by former officials in India are mostly self-serving and when they display traces of honesty, they are usually worthless. The two authors discussed here had successful careers in the civil services of India. They had the opportunity to observe crucial decisions made at critical times. Readers don’t look for salacious details but for perspective on what went wrong. Habibullah imagines Rajiv’s India as a Camelot; in reality it was an interregnum between the latency of a host of problems from Assam to Kashmir and the later, violent, upheaval in these states. Sidhu’s story is believable but only in snatches. The full story of these conflicts is unlikely to

come from official reminiscences. That will have to wait for scholarly elaboration.